Trading Defensively: Managing Tested Positions

With the spread of the novel coronavirus outside of China, the entire world is now wrestling with a very serious threat. Furthermore, many investors are grappling not only with ensuring that they stay healthy, but that their positions—many of which are now being “tested” by the global economy’s response to the pandemic—stay healthy too.

As a reminder, so-called “tested positions” are those that move into negative territory from a P/L perspective, or those that make an investor or trader uncomfortable because some aspect of the original assumption underlying the trade has changed.

The global community is currently fighting to treat the nearly 300,000+ known people infected with COVID-19, as well as to contain the virus and protect those who are still healthy.

This may be the widest-reaching coordinated defensive effort in human history since the conclusion of World War II.

Uncertainty over the ultimate impact of the coronavirus has likewise thrown global financial markets into a period of dramatic volatility. This dynamic means that many individuals are not only literally fighting for their lives, but also for their financial lives.

One positive to take from all this is that the previous financial crisis, which seemed like a nightmare during the time, spawned over a decade of upward movement in global equities, as well as appreciation in a host of other asset classes.

While there’s no guarantee that the current crisis will play out in the same way, the long history of booms and busts in global markets suggests that asset prices will at some point recover.

Obviously, it’s difficult to say when that might be—the second half of 2020, the first half of 2021? It’s anyone’s guess at the moment.

The high probability of a recovery doesn’t do much to help those who are currently grappling with difficult positions in the market, either.

When a position or portfolio gets “tested,” investors and traders are forced to take a long look in the mirror and make what can often be difficult decisions.

A tested position can materialize in any investment class, whether it be stocks, options, futures, commodities, real estate or anything else.

For example, there are likely more than a few investors in Boeing (BA) who are currently experiencing discomfort associated with recent developments in the stock.

For starters, Boeing is well off its all-time high of nearly $400/share. BA stock has dropped roughly 75% in the last 12 months. As if that weren’t enough, the company recently suspended its dividend, and is said to be seeking upward of $50 billion in assistance from the U.S. government.

Boeing was undone in 2019 by safety concerns related to its now-infamous “737 Max” airplane model. Compounding that problem has been the outbreak of the coronavirus, which has greatly impacted the travel industry and is expected to further pressure demand for Boeing’s jets.

Current investors in BA are now faced with a difficult set of choices, which could involve any of the following: hold the existing position, reduce the existing position, close the existing position, add to the existing position.

The ultimate route selected by an investor will depend on their risk profile, liquidity needs, tax situation and outlook on Boeing stock, among many other considerations.

Beyond normal stock positions, other securities, such as options and futures, can also be “tested.” These situations require an additional layer of consideration because unlike stocks, positions in options and futures expire.

To wit, a long Boeing holder who decided to pull a Rip Van Winkle during the coronavirus outbreak and get cryogenically frozen until an effective vaccine is available might decide to hold the stock through this period, hoping for better days ahead. Since Boeing stock only “expires” when it goes to zero, a long-term holder doesn’t have to worry about actively managing the position—assuming he or she decides to hold it going forward.

On the other hand, options and futures traders must often make decisions based not only on perceived value in a given instrument but also on “time until expiration,” called “duration.”

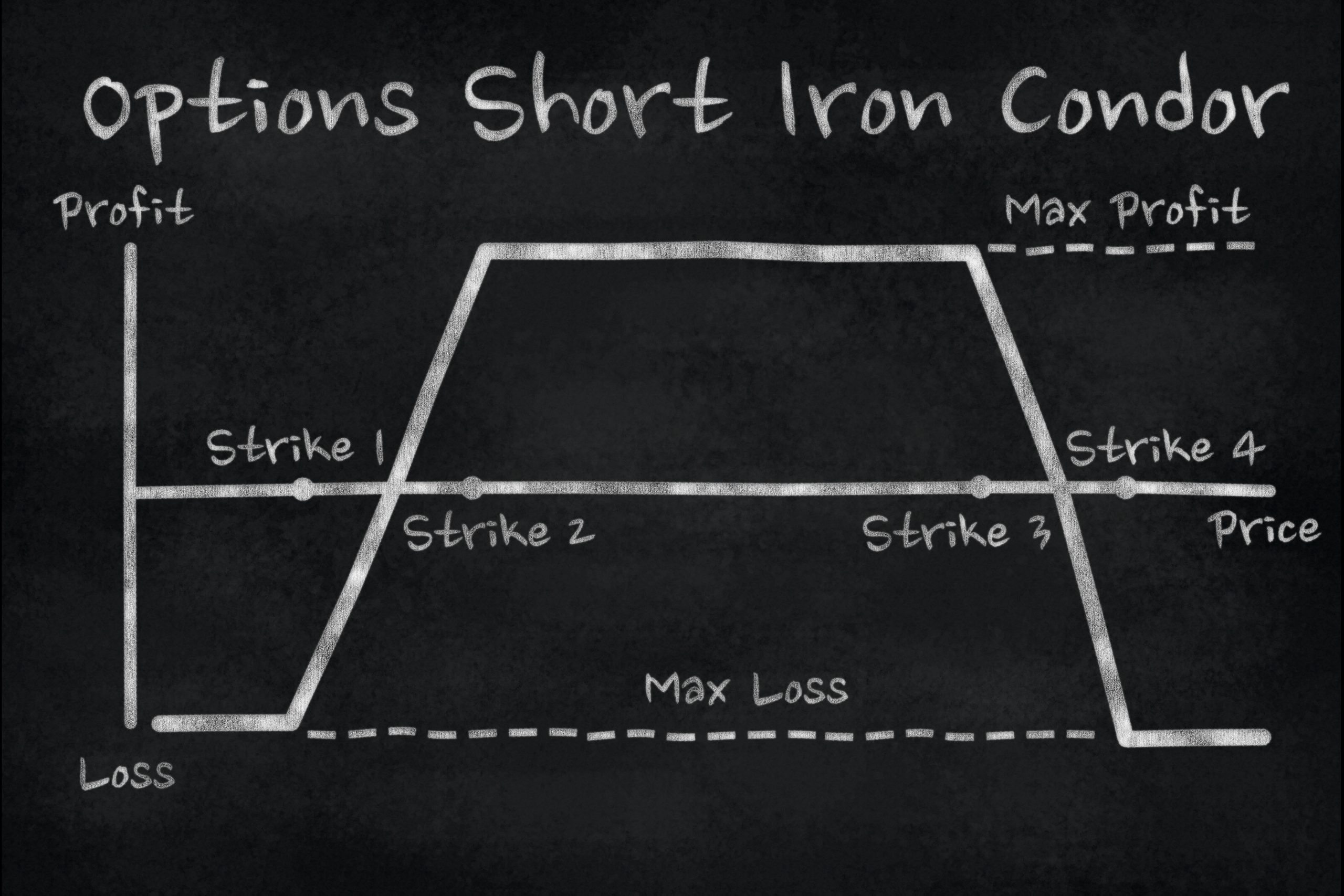

For example, if an options trader viewed implied volatility in SPY as “rich,” he or she might decide to sell premium. And while selecting a strike to sell is paramount, so too is selecting the duration of the trade. The choices range from one month to over a year, and everything in between.

This duration factor also means that when an options position gets tested, the trader has a wider set of choices available in terms of position management:

- Hold the position

- Reduce the position

- Close the position

- Add to the position

- “Roll” the position

While the first four choices above are similar to a stock position, the question as to whether to “roll” a position may not be familiar to all traders.

When executing a roll, a trader closes the original near-term position in favor of simultaneously opening the same (or similar) position in a longer-dated expiration. During a roll, the trader may also elect to adjust the strike(s) of the position.

The crux of every rolling decision revolves around time. When a tested options position approaches expiration, there are fewer opportunities for it to climb back to break-even, or positive territory—too much sand has already passed through the hourglass.

Rolling is basically a modified version of “holding” a position because it extends the time until expiration and gives a position more time to work. A rolling decision is typically only taken when a trader believes their original assumption for taking on the exposure is still valid, among other considerations.

Whether an options trader decides to hold an existing position until expiration, or roll it into a longer-dated expiration month, relies on the premise that “patience” in volatility trading is a golden virtue.

And according to previous research conducted by tastytrade, patience may also be one of the most important tools in an options trader’s utility belt.

Specifically, the research addresses the question of whether “close it” or “keep it” has performed better historically when it comes to position duration for tested trades.

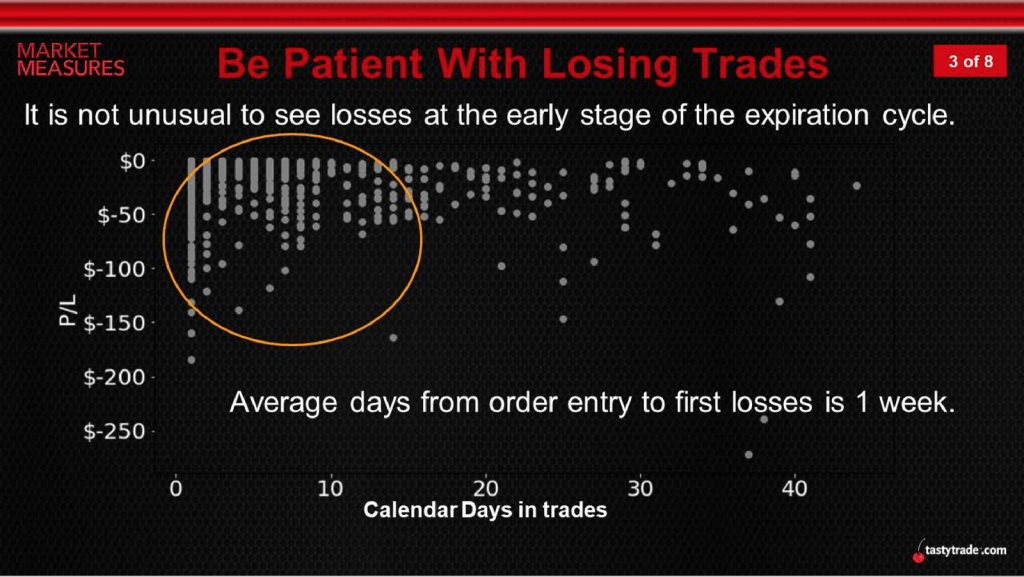

In order to produce the data necessary for this analysis, the tastytrade research team ran a comprehensive study incorporating the following parameters: sold 16 delta strangles in SPY with 45 days-to-expiration (DTE) from 2005 to 2017.

The goal of the analysis was to isolate the losing trades and then filter the data for discernible trends. The slide below highlights how losing trades tend to cluster toward the early part of the trade cycle:

As illustrated in the graphic above, data from this market study indicates that as time passes, trade performance tends to improve.

Further analysis of the backtest results showed that after breaching a loss, 96% of the losing trades in the study ultimately saw profits (on average) in the aftermath. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that it takes about a week for a “tested” trade to correct itself (on average).

More importantly, the data revealed that by holding all losing trades through expiration, the average P/L of the combined trades was positive. Readers seeking to learn more about aforementioned study focusing on rolling decisions may want to review the complete episode Market Measures when scheduling allows.

A previous episode of Futures Measures may also be of interest to market participants who want to learn more about managing tested futures positions.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.