How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Deflation

Why DO mainstream economists FEAR LOWER PRICES?

Unemployment recently dipped to 4.6% as the economy added 531,000 jobs, according to the monthly jobs report issued in November by the United States Department of Labor. Those top-line numbers always make headlines, but a truly startling statistic is buried deep in the report.

For 14 straighat months, more than 100 million able-bodied Americans have been out of the workforce. That means only 61.4% of the labor pool is on the job. That percentage has declined steadily for two decades, and it’s continuing to decrease even now with 10.9 million jobs open.

To be fair, the 100-million figure includes retirees, students, family caregivers and discouraged job seekers no longer looking for employment. But most of the jobless don’t fit those categories.

Armchair economists and political pundits have been trading barbs and assigning blame for the trend since at least 2001, when 66.7% of potential workers had jobs. They trace the decline in participation to everything from low wages to an understandable reluctance to uproot a family and move to where jobs are available. They blame Amazon’s domination of retailing. They blame Biden. They blame Trump. And now they blame COVID-19.

But what about the march of technology and the U.S. monetary system’s commitment to debt-based growth? Don’t they deserve some of the blame?

Jeff Booth on deflation

In January 2020, just as the pandemic was beginning to ravage the global economy, Canadian entrepreneur Jeff Booth released his book The Price of Tomorrow—Why Deflation is Key to an Abundant Future.

Booth serves as chairman of CubicFarm Systems, which develops equipment for year-round indoor vertical agriculture. He has started companies that specialize in agribusiness, real estate and technology. Through it all, he has promoted the principle of “more for less.”

He offers a simple thesis for understanding a debt-based financial system like the one in the United States: A government that creates debt to counteract the deflationary influence of technology could eventually wreck its economy.

While the U.S. may not have reached that extreme, recent trends suggest an unwillingness to embrace deflation that will aggravate chronic structural problems.

The pursuit of inflation causes many of the challenges facing the U.S. and other nations, Booth maintains. The policy centralizes wealth and power while abetting inequality, polarization and the rise of opportunistic fringe candidates.

Pursuing inflation reinforces a system that leaves many citizens feeling impoverished even though technology is raising their standard of living.

In his book, Booth asks a fundamental question: “What if, instead of trying to stop deflation at all costs, we embrace it? As technology spreads, deflation happens at the rate it should. Deflation becomes something celebrated because it means that we are getting more for less. We allow ourselves to accept abundance.”

1930’s-style fear of deflation

Why are mainstream economists so fearful of deflation?

Keynesian-influenced professors taught them never to question inflationary policy. The argument goes that when prices fall, consumers will wait for prices to fall further, thus precipitating a collapse in demand.

Booth argues that artificially induced inflation ends up increasing the cost of essentials, such as food, rent and transportation. Deflation, however, tends to link to things that don’t matter.

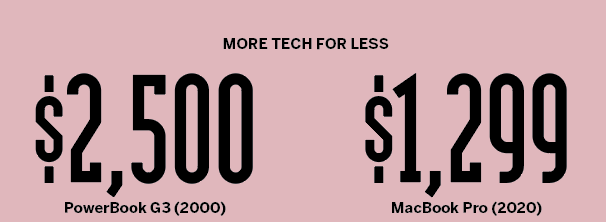

Technological progress has spawned deflation everywhere. Cell phones used to cost $2,000, but now they’re 10 times as powerful for a quarter of the price. The price tag for a television set has declined 98.7% in inflation-adjusted dollars since 1977.

“Does technology reduce price? Yes. That is undeniable,” Booth says. “Do we all benefit from the fact that technology gives us more freedom? Yes, that’s why we use it.”

Booth declares that as rational beings, consumers want more for less. That’s why technology companies win.

“It’s why we use Google and Amazon,” he writes. “They give us more value, we get more choice, we get cheaper products versus the status quo. Technology does that faster at an ever-increasing and exponential rate.”

Smartphones create value and provide benefits by eliminating the need for other products, including cameras, scanners, entertainment systems, banks, email networks, calendars, board games, and printed books, magazines and newspapers. Those displaced products have effectively become free.

Consumers benefit from free or reduced-priced goods, but the economic system is built on credit and would collapse with deflation, Booth asserts.

Case in point: Since 2000, governments around the world have created $185 billion in new debt. But the return on that debt hasn’t generated significant economic growth. So despite all that stimulus, the increase in the money supply produced only $46 trillion in global growth over those two decades.

History shows that every single new dollar of debt has created less economic growth than the dollar that preceded it. But even with diminishing returns from newly created money, America remains committed to what amounts to fiscal madness.

Today, every new dollar of debt creates an uptick in GDP of fewer than 35 cents, according to the Federal Reserve Board and Hoisington Investment Management. That’s well below the 70-year average of $0.61 and continuing to decline.

So, a question arises: Can we still enjoy abundance when prices and wages deflate? If they fall in unison, it shouldn’t be an issue.

How does this truism go ignored, and why do Americans fear deflation?

Well, many economists blind themselves to reality by persistently looking back upon the 1950s, when returns from debt were substantially higher. Meanwhile, many of today’s economic policies harken back to the 1930s and 1970s while failing to adjust to the structural impact of technology over the last 40 years.

Even when they’re wrong, central bankers tend to stick around a while. Then they move on to jobs in banks where they profit from the prevailing system or retire to universities to teach another generation of economists to seek inflation. Their memoirs chronicle their bravery in confronting the problems they helped to create.

Other deflationary voices

Robert Shiller has written extensively on the deflationary influence of technology. In a 2003 Wall Street Journal column, he suggested that technology linked to deflation can cause “revenge effects” in an economy.

Shiller worried that economies faced “a cascade of consequences from recent advances of information technology like the World Wide Web, which became available to the public in 1994.”

That was 18 years ago, long before Google emerged as a public company.

But the debate about technology and deflation has been on display over the years between academics and technology-focused entrepreneurs.

In 2015, for example, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen suggested that technology creates higher living standards and lower prices but isn’t measured effectively in the nation’s economic statistics.

“While I am a bull on technological progress,” Andreessen wrote, “it also seems that much of that progress is price deflationary in nature, so even extremely rapid tech progress may not show up in GDP or productivity stats, even as it equals higher real standards of living.”

Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers challenged Andreessen. “It is…not clear how one would distinguish deflationary and inflationary progress,” Summers replied. “The price level reflects the

value of goods in terms of money, so it is hard to analyze without thinking about monetary and financial conditions.”

Summers speaks to how price levels are measured: In nominal currencies. But what’s the real issue

at hand? Is deflation so bad that government should confront it with policy that reinforces structural problems?

In a 2017 essay called “The Illusions Driving Up U.S. Asset Prices,” Shiller tackles the origins of monetary policy that result in the consequences Booth described. Shiller notes that the Fed, like other central banks, has been debasing its currency.

A Google search by Shiller indicated the term “inflation-targeting” started appearing more often in the 1990s. He says the pursuit of positive inflation—or price stability—began after the 1991 recession. He also cited Summers, who said Americans would display “irrational” resistance to falling nominal wages if the Fed targeted a “zero-inflation regime.”

Technology had a significant deflationary impact while the Fed’s 2% target rate, which Shiller called “feel-good policy,” took hold. The Economist noted in 2019 that the U.S. had experienced only a small increase in consumer-goods prices, except for food and energy, since 2000.

Booth maintains that inflationary policies not only fail to stop tech-driven deflation but also concentrate power and wealth.

Inflationary policies not only fail to stop tech-driven deflation but also concentrate power and wealth.

Academics and economists—the people driving 20th-century monetary policy—don’t seem to comprehend the exponential impact of deflationary technology. In a recent example, Bank of England Chair Mark Carney compared artificial intelligence to harnessing the power of electricity.

“Electricity was never going to be smarter than humans,” Booth noted, adding AI’s path to superseding humans may take 20 to 50 years, but along the way it will drive exponential deflation.

To understand exponential growth, imagine putting a single drop of water on the 50-yard line during the first minute of an NFL game. A minute later, add two drops. Keep doubling the number of drops every minute. The stadium would fill with water in about 44 minutes—approximately the end of the third quarter.

Booth provides another alarming example in his book. To understand compounding growth, suppose that a single sheet of notebook paper can be folded seven times. How big would a piece of paper have to be to fold 50 times—the size of the Empire State Building? Nope. It would have to stretch the 93 million miles from Earth to the sun.

How the system works

Booth notes that society can continue down the path of denying deflation exists and “pretend to get paid less to save jobs.”

But he argues that humankind can progress by adopting a deflationary system that would enable technology to create and broadly distribute abundance. Otherwise, people are simply focused on the risk of a brave new vision.

“Printing more money is just concentrating that risk,” Booth says, adding that in the inflation-based economy people are actually paid less in real terms than they would be after the acceptance of deflation.

The concentration of power in various sectors, combined with the effort to chase inflation, forms a negative feedback loop that drives inequality of wealth.

Here’s how it works: Apple and its cell phones, computers and other devices wield deflationary power by displacing bank tellers, boardgame makers and manufacturers of everything from compasses to cameras.

Next, the government offers dramatic unemployment benefits to those displaced workers and provides even more significant capital to bail out investors who owned the companies facing obsolescence. Booth notes that America bails out rich corporate failures and socializes their losses. Refusing to allow unsuccessful businesses to fail compounds the structural problems.

In the next phase, new capital enters the system. This inflation reduces consumer purchasing power while driving up the cost of food, rent and energy. Finally, money flows to the investor class, including other deflationary companies engaging in the same cycle as Amazon, Tesla and Alphabet. These companies with monopoly power now invest in deflationary technology like artificial intelligence that will displace more workers, and the cycle begins again.

Now, while Congress sharply focuses on fiscal policy, observers might want to give monetary policy a second look.

Inevitable inflation versus deflation

Competition between inflationary and deflationary forces will drive greater instability in the future, Booth suggests.

He notes that technology has driven down the costs of products and services but that the financial system relies on the old definition of economics—“the management of scarce resources.” But that scarcity occurs because of the debt-based system.

And consumers will feel the dramatic advance of technology in the next decade in virtually every sector of the economy with the introduction of 5G, the growth of artificial intelligence and the proliferation of robotics.

Meanwhile, it remains to be seen how governments will manage three industries that have experienced incredible inflation over the last four decades thanks largely to dramatic debt-based support by the U.S. government: Education, healthcare and housing.

From 1977 to 2021, the price of new houses increased 385.4%, medical costs rose 820.8% and college tuition soared 1,421.5%.

So, how will a tech-driven, deflationary economy respond to those hikes in the cost of education and housing, two bedrock institutions?

Americans anticipate that the value of their homes will never stop appreciating in value, and politicians are aware that 25% of household “wealth” is linked to a primary residence. (It’s 75% in China, where the state firmly holds centralized power.)

However, Booth notes that housing prices could fall because of technological advances in construction and 3D printing, offsetting the increasing cost of labor in the industry. Booth also focuses on the bigger picture and the declining returns based on new government debt.

“People who think their house goes up forever don’t realize that it took $185 trillion of stimulus against $46 trillion of economic growth,” he says. “Now, if you believe that the next 20 years could have $400 trillion of credit growth, to grow economies by $40 trillion, then housing might be an excellent place to [invest].”

And what about education? In today’s tech-driven world, education is largely free with the right internet connection, but getting credit for educational achievement is not.

“Certification only comes because people believe they are going to get a higher paying job because of the certification,” says Booth. “And that’s not true today. It certainly won’t be true in five years.”

The 1999 film Good Will Hunting suggested one could receive the equivalent of a Harvard degree with just a library card and late fees. Today, YouTube and countless open-source online programs offer access to a world-class education. Post-COVID, fewer younger Americans are enrolling in universities and community colleges.

When people pay for a college degree merely to advance in the system itself, the government-university pact begins to look more like a multi-level marketing platform than a reliable source of economic advancement. So, a shift in education appears inevitable, and the price model will likely change. That could enrage graduates with massive student loan debt.

Meanwhile, healthcare remains a heavily financed “rail” of American government. Costs should be declining in the sector because of technological innovation, but the government is incentivizing rising costs and aging baby boomers are availing themselves of more medical care. Those factors make it difficult to roll back the inflationary pressure in a healthcare system that represents 16% of the U.S. economy and is a significant source of wages.

One can debate the U.S. economy’s future as systemic forces collide. It’s free-market economics versus what feels like technological feudalism, centralization of power against decentralization, and inflation against deflation.

Not many leaders have recognized those conflicts, and some might even be using them to gain advantage in the political tribalism that lies ahead.

America bails out rich corporate failures and socializes their losses.

“Think about what technology looks like in five years,” Booth suggests. But doing so requires an ability to comprehend the exponential impact of artificial intelligence, robotics, cryptocurrencies and deflationary forces.

He’s forcing a conversation, one sorely needed as so many forces collide. The time is at hand when emerging technologies make most people as useless as horses, the only choice is to play by the established rules of employment and investing. That might be the best-case scenario.

The path for Investors

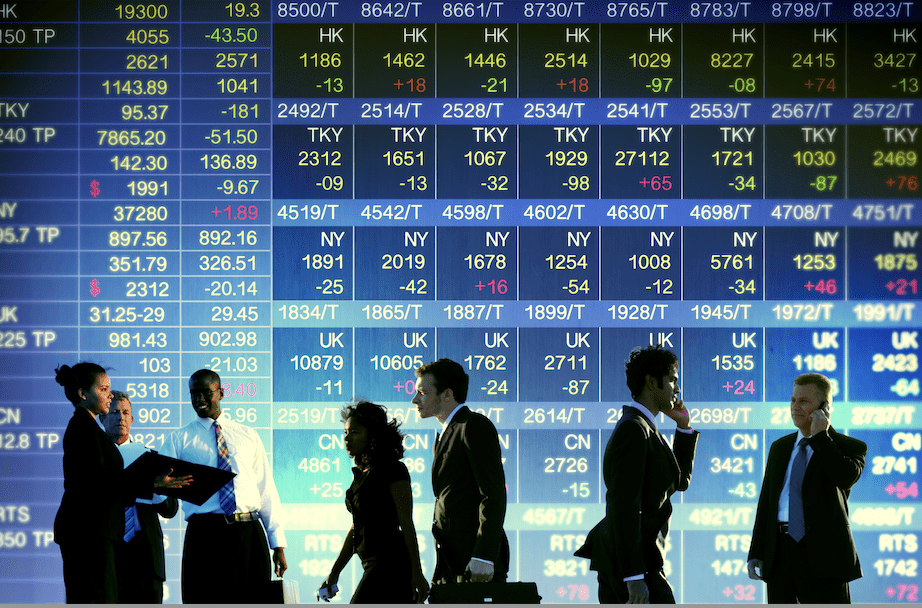

So, what’s an investor to do in an economy where deflation drives down prices to meet the expectations of consumers and businesses?

Some experts suggest that guarding against inflation requires exposure to rising commodity prices, growing bank deposits, foreign markets and foreign currencies.

Companies like Chevron (CVX) and EOG Resources (EOG) have strong balance sheets and have appreciated, thanks to the recent surge in oil prices.

If JPMorgan Chase’s suggested supply-demand imbalance accelerates in 2022 and beyond, producers with low debt and significant amounts of reserves will benefit.

Then there’s the suggestion that combining exposure in foreign markets with gold, a historical inflation hedge, offers a defensive play. But gold remains below its all-time highs from a decade ago, and foreign currencies in resource-rich nations face macroeconomic challenges.

Meanwhile, most of the challenges to supply-demand balance stem from supply chain bottlenecks that could disappear in the second half of 2022.

Then there are the regional and community banks. While mergers and acquisitions continued at a pace of 3% to 5% annually before the pandemic, banking loan books have been anemic over the last 18 months. Since Booth penned his book, the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE) has risen from $56 to $75 (33.9%).

But the Nasdaq 100, led by companies that have fueled tech-driven deflation, has surged from $222 to $390 (or 75.6%).

This suggests a relatively simple alternative

strategy. The deflationary approach is to own stock in companies that have been replacing workers

with robots.

Despite their higher valuations, investors can continue to benefit from owning stock in robotics companies, A.I. firms and semiconductor producers like Qualcomm. The same goes for FAANG darlings Meta (FB), Amazon (AMZN), Apple (AAPL), Netflix (NFLX) and Alphabet (GOOG) (formerly known as Google).

And according to IBM’s U.S. Retail Index, the impact of COVID pulled the consumer curve of e-commerce forward by five years and kicked off even greater investment in digital supply chains and payment systems.

Booth has also argued in favor of bitcoin because of its deflationary nature.

“Bitcoin is already the best store of value on the planet measured by stock returns, or price returns over the last 13 years,” Booth says. “Everything measured in bitcoin is coming down in price. It’s telling you the truth. It is a free market. When I say deflationary currency, that allows for deflation. If we have real growth, we have real growth, and prices should rise, the price should rise. We shouldn’t manipulate them.”

In the next decade, the number of able-bodied Americans out of the workforce may surpass the number working, while the debt-based system continues to drive asset prices higher and enrich wealthy shareholders in companies that are replacing workers with robotics.