How Not to Start an Energy Revolution

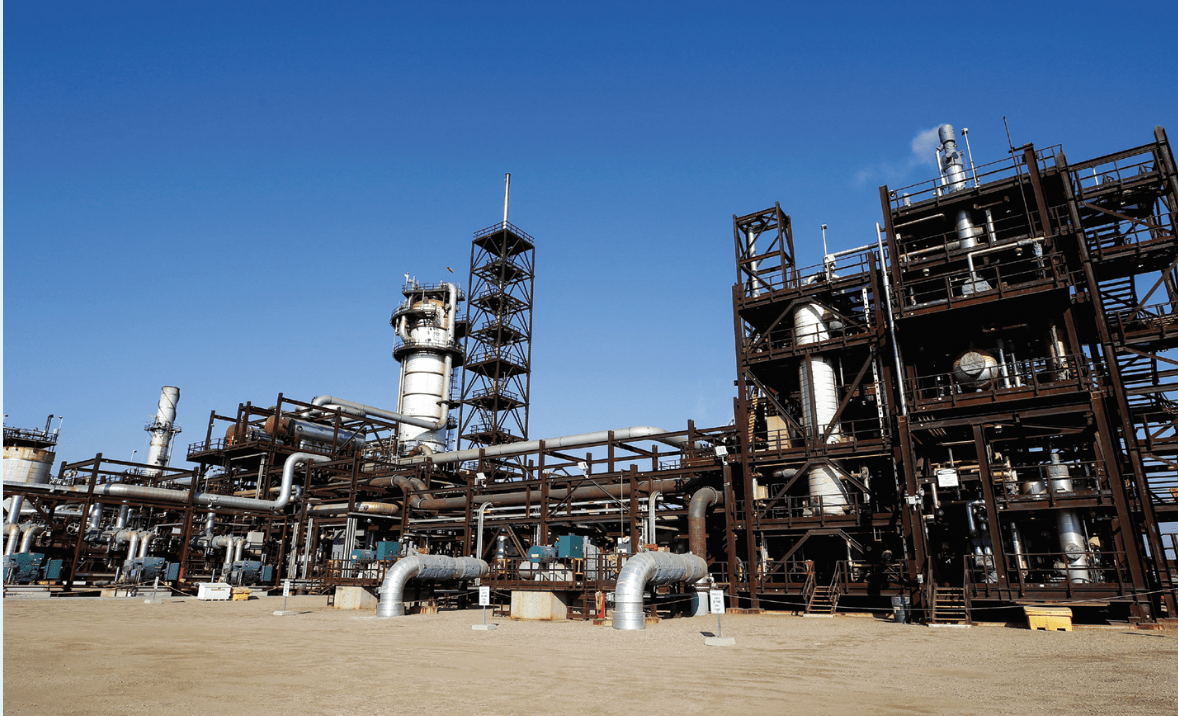

Lack of capital is preventing the petroleum industry from satisfying the public’s desire for abundant oil and natural gas

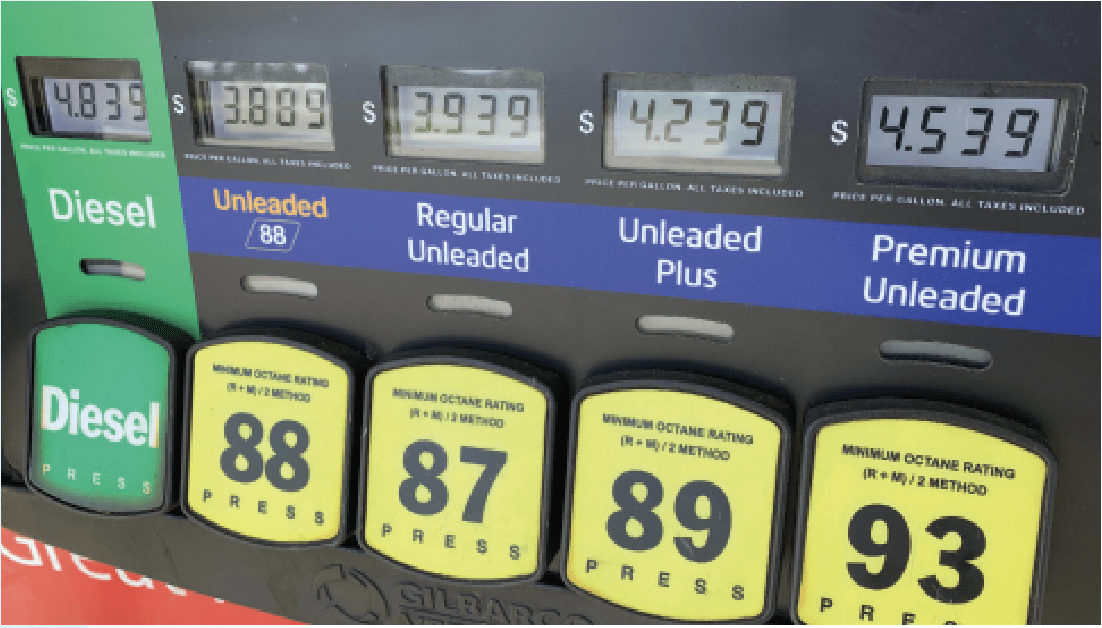

President Joe Biden’s administration and the cable news talking heads blame $115 per barrel of oil and $5 a gallon of gas on a panoply of causes that include the reopening of the economy, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and “price gouging” by suppliers.

But anyone working in oil and gas finance knows those reasons are spurious. Prices are rising because the energy sector is hungry for capital investment. The shortage of funds could threaten international financial stability and accelerate a global commodity shock that would make the transition to a clean energy economy even more complex.

Already, rising oil and gas prices have fueled unsustainable price increases in industries ranging from fertilizer and food to shipping and trucking. The ripple effect will be felt throughout 2022 and may cause dramatic political shifts worldwide.

Investors who exploit those disruptive trends in the flow of capital will benefit as capital dislocation in the energy sector accelerates and produces high returns for certain industry players.

ESG intervenes

In January, Saule Omarova, a Cornell University law professor and former Treasury Department advisor, asked the Biden administration to withdraw her nomination as head of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency.

Omarova, who grew up in Kazakhstan and earned a bachelor’s degree in Moscow before coming to the United States for graduate school, had made headlines when her statements from previous years about oil and gas investment became public during the confirmation process.

“The way we basically get rid of those carbon financiers is we starve them of their sources of capital,” she had reportedly said.

Omarova’s critics argued that she wanted to bankrupt the U.S. oil and gas industry, but anyone paying attention to the sector should know that energy producers were already bereft of capital.

The shortfall began a decade ago when the environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) movement gained momentum in its effort to decarbonize the global economy. As investors shifted funding to climate change mitigation, borrowing costs rose for oil and gas producers.

Ten years ago, capital costs ranged between 8% and 10% for energy projects whether they were for oil and gas or for renewables, according to Goldman Sachs analyst Michele Della Vigna. By the end of last year, capital costs for renewable projects ranged from 3% to 5%, while long-cycle oil and gas projects were paying 20%, she said.

Renewable power generated more investment than traditional carbon fuel sources for the first time last year, Della Vigna noted.

Socially conscious capitalism

Socially responsible ESG investing began in the 1950s with pension funds and picked up steam in the socially conscious 1960s.

When ESG-oriented investors began to shun sectors like tobacco, the sector consolidated dramatically and formed a global oligopoly that increased consumer prices yet still generated significant tax dollars.

BlackRock’s Larry Fink has emerged as a significant voice in ESG’s climate change crusade, vowing in 2017 to use the alternative asset manager’s $10 trillion in assets to change how people behave.

Last year, Fink wrote a letter to CEOs stating that “we know that climate risk is investment risk. But we also believe the climate transition presents a historic investment opportunity.”

Today, BlackRock has sizable investments in

clean energy assets and will benefit from a global transition to renewables. Fink has even advocated shifts in the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s mission to help support clean energy in developing nations.

But BlackRock still maintains sizable stakes in global oil-producing giants like Chevron, Shell, ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, and it has positions in large pipeline projects and other carbon-based energy systems.

Environmental advocates argue that BlackRock isn’t doing enough to mitigate climate change despite Fink’s influence. Activists lament that BlackRock continues to invest in oil and gas projects and demands that the firm stop providing funds to expand oil or gas production. Sierra Group also argues BlackRock should jettison all new oil and gas projects.

Activists contend that if shame doesn’t cause companies to divest or defund, then bare-knuckled boardroom advocacy and new compliance and

scoring metrics will introduce business leaders to their willing replacements.

Meanwhile, regulators are pressing for accountability for harmful emissions. The Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed the most rigorous audits since the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. It would require recording direct and indirect carbon emissions and listing climate risks across supply chains. That would increase compliance costs and might reduce the number of initial public offerings.

The rules are great news for auditing firms like KPMG and Deloitte. They’ll make pie charts depicting a public company’s electricity generation sources down to the last kilowatt. Higher compliance costs will likely prompt an increase in energy costs.

In the near future, the media seems likely to scrutinize corporate emissions more closely and could potentially expose companies to lawsuits and shareholder pressure.

The movement to mitigate carbon emissions has brought political and economic change for several of the largest energy producers. Last year, three major events rocked the global oil and gas industry.

First, a Dutch court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to cut emissions drastically by 2030. The company must radically change its business model to meet the government standards.

Second, 61% of Chevron shareholders demanded that the company reduce “Scope 3” emissions to curb impact on the climate. Those emissions are related to assets Chevron does not own or control, but they indirectly affect the company’s supply chain and can be costly to track.

Finally, ExxonMobil lost two director’s seats to Engine No. 1, the ESG-oriented activist exchange-traded fund, even though the fund controls only a small number of shares. It happened because Engine No. 1 had the support of larger institutional investors, including BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, to press for climate mitigation.

Bigger disruption

Some proponents of ESG no longer seem content just to shift capital from oil-intensive projects to sustainable ones. They want to constrain companies that emit carbon.

One example is the International Energy Agency (IEA), a Paris-based intergovernmental body that’s seeking to reach net zero carbon by 2050.

The IEA wants governments to refuse approval to new oil and gas fields and coal-power stations. It would like to eliminate the sale of fossil fuel boilers by 2025.

Despite advances in alternative energy production, demand for fossil fuels hasn’t declined.

More than 400 IEA milestones over three decades would require $4 trillion of investment by 2030. The goals include the quadrupling of wind and solar power capacity.

But one wonders if that agency’s leaders understand that procuring the raw materials needed for solar and wind systems requires burning large amounts of oil, gas and coal. Do they realize replacing baseload energy capacity is extremely expensive? Has anyone at the agency spoken with a bio-engineer or middle-of-the-road energy economist since 2015?

Switching to wind and solar on the scale the IEA advocates would require hundreds—if not thousands—of metric tons of plastics, purified materials, concrete and steel, not to mention drilling into the earth to mine for lithium, nickel and rare-earth metals.

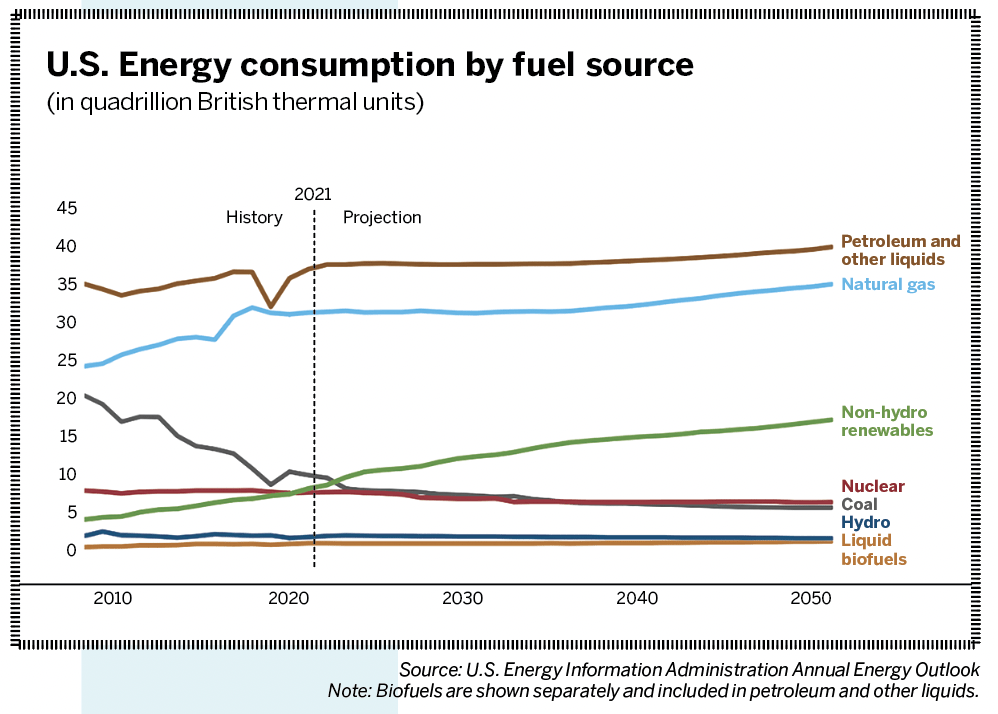

But despite that massive effort, the U.S. Energy Department predicts that alternative energy systems will barely make a dent over the next three decades in the sector where oil dominates: transportation.

Yet, those goals, coupled with the limitations imposed by the Paris Climate Agreement, are increasing costs and exacerbating capital challenges.

In 2019, the European Investment Bank—the top lending arm of the European Union—eliminated lending to fossil fuel projects. But the EIB took its capital allocation rules to a new level. In 2022, the EIB stopped funding any “polluting company” that wanted to finance low-carbon plans—for example, an oil company that wanted to expand into solar or wind production. To comply, applicants must also outline their future decarbonization plans.

Activists claim the scalps, but banks will decide

the fate of oil and gas. In 2019, Goldman Sachs stopped funding crude exploration and thermal coal mines. Instead, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and the Wall Street crowd promised dramatic changes to their carbon-based lending practices.

Blackstone Group, the private equity giant, is withholding support from shale oil and gas exploration and production. Others have followed suit.

Still, demand for fossil fuels has recovered from the COVID-19 crisis, returning to more than 100 million barrels per day, while the cost of cleaner fuels is surging because of price swings for lithium, nickel and cobalt.

Higher oil and natural gas prices should accelerate the conversion to cleaner sources, but Europe has struggled to produce enough renewable energy. The transition to wind and solar hasn’t met demand since the economic reopening after the worst of the pandemic. The problem began long before Russia invaded Ukraine.

Drying up oil and gas capital is creating a dislocation in the markets that could drive the global economy into a recession in the next 12 months.

But don’t expect U.S. producers to come to the rescue by increasing production to lower oil prices.

Drill, maybe, drill?

A capital crunch in oil and gas markets is impending, according to banks, credit agencies and major oil producers. Think of it as a $500 billion hole in the investment capital required to produce the oil needed to meet global demand by 2025, Moody’s Investors Service suggests.

“While international crude and U.S. gas have risen more than 50% and 120% [in 2021], respectively, drilling outlays are only forecast to increase by 8% globally,” Moody’s said in a report.

The capital crunch caused JPMorgan to project in June 2020 that oil prices could reach $190 per barrel by 2025, signaling that this challenge was on analysts’ minds at the onset of the pandemic.

Still, many U.S. producers don’t plan to open the taps even at those prices.

It might be news to some, but the future of American energy still rests on the back of U.S. oil and natural gas producers. U.S. demand for oil and gas demand will increase well through 2050, according to the Department of Energy.

The IEA Energy Outlook 2022 report foresees “a variety of economic scenarios as population and economic growth outpace energy efficiency gains.” Consumers will continue to rely on petroleum and natural gas because wide-scale adoption of alternative energy systems like wind and solar will take decades, the report says.

In fact, transportation is expected to help increase annual gasoline consumption by 34% (4.3 trillion quads to 5.8 trillion) by 2050. Annual natural gas consumption will increase by 10% by mid-century.

The challenge lies in procuring capital to fund future production to meet that demand.

In March, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm urged energy producers to increase their output to help mitigate high gasoline prices.

U.S. producers responded with little enthusiasm and pressed for a conversation with the White House about the lack of social and economic incentives. Short-term price incentives to drill were overshadowed by longer-term policy challenges facing the cash-intensive industry.

While the Biden Administration isn’t banning oil and gas production in the future, policies suggest hostility to the sector.

Besides pipeline cancellations and drilling restrictions on federal lands, the White House has

set timelines that would curb long-term demand

and investment.

Biden has pushed the nation to become a net-zero carbon emitter by 2050 and demanded that the U.S. reach 100% carbon-free electrical generation by 2035. The target of 50% electric vehicle sales by 2030 would put a sizable dent in gasoline sales.

Companies won’t drill new wells or expand upstream capacity with sunsetting principles in place. A 15-year limit on an oil well’s production drastically changes the return on investment when the traditional life cycle can last 30 years or more.

Companies won’t drill new wells or expand upstream capacity with sunsetting principles in place. A 15-year limit on an oil well’s production drastically changes the return on investment when the traditional life cycle can last 30 years or more.

Despite significant short-term price incentives to drill, limiting the lifespan of new wells will keep investment near record lows in 2022. Even worse, rising inflation will limit the amount of new production. Up to 20% of all 2022 capital expenditures are necessary to maintain current production, thanks to the rising cost of steel, wages and other inputs, according to Forbes magazine.

Even with oil prices at $105 in April, many producers remain committed to maintaining current output. For example, Pioneer Natural Resources’ chief executive Scott Sheffield told Bloomberg in February that his company wouldn’t change its growth plans.

Price incentives weren’t expected to increase production by more than single digits at Diamondback Energy, Continental Resources, and Devon Energy. Energy producers have learned their lesson about boosting production in response to short-term price movement.

In 2014, energy producers reacted to oil prices above $100 per barrel by expanding production in the shale patch. The surge in output resulted in much lower oil prices. That, in turn, can reduce stock prices and prompt shareholders to demand better cash

flow management.

While environmental activists drive up capital costs and hammer away at boards of directors, shareholders will continue to push for stronger returns. The response? Do virtually nothing.

Oil producers will continue to reduce balance sheet debt, repurchase shares, boost dividends and consider diversification—especially if they’re subsidized to produce alternative energy.

As with the tobacco industry, energy producers facing a capital crunch will consolidate, and smaller players will shed non-producing or stalled projects.

It’s getting more expensive to switch to cleaner fuels, thanks to BIG swings in the price of lithium, nickel and cobalt.

Contemplating the future

Another consideration is seldom discussed: Investment bank boards of directors drive capital decisions, and their members are social creatures.

Not many banking executives want the public relations headaches associated with financing oil, gas or coal. Corporate boards don’t want environmental activists gluing their hands to office doors, something that happened at BlackRock in January 2020.

Bankers can do without the negative press and the activists who show up on their lawns at midnight. They don’t want lectures at cocktail parties. They want to be liked. They want to fit in.

So, bank officials keep quiet and nod when compliance officers or newly created chief resource officers recommend that they don’t fund a project because of ESG concerns.

But that only perpetuates the silence about the elephant in the room.

Most politicians and large financial institutions must know the transition to renewable energy will require staggering social and economic costs. Not many are willing to step forward and come clean about the cost or the sacrifices.

For years, politicians have promised a simple, cost-effective transition to alternative energy. It’s not going to happen.

“Cheap” means more than $30 trillion in infrastructure and renewable resource investment by 2030 alone, according to The World Energy Outlook 2021 report from the IEA. Common sense dictates that higher costs of capital will drive up energy prices.

It was easy to kick the costs down the road. But now Ukraine and Russia—two countries that export wheat, corn, nickel, oil, natural gas, steel and fertilizer—are increasing the cost of everything and sharpening the focus on this expensive transition and the recent European energy crisis.

Last fall, as soaring electricity bills set records across Europe, the head of the IEA tried to claim that the shift to renewables wasn’t the problem. That kind of talk only makes matters worse.

Was it a coincidence that the runaway prices followed closely upon the continent’s efforts to make a rapid transition to renewables and the capital squeeze on traditional energy?

Solar and wind are cost-effective in the early stages of the conversion but rise significantly with the attempt to replace fossil fuels for balancing and baseload electricity, according to Lucas Toh, a board member of the SIPA Energy Association at the Columbia University School of International Public Affairs.

Oil and gas are the lifeblood of the global economy, much like oxygen fuels the human body’s circulatory system. Their efficiency, portability and relatively low costs have driven economic growth for decades.

Reducing carbon emissions requires carbon-based fuels, especially in emerging and frontier markets that are taking intermediate steps in the transition

to renewables.

People talk

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, some were beginning to recognize the sobering and costly reality of the transition.

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman noted in November that the Federal Reserve has ignored the inflationary pressures of ESG. “Stakeholder capitalism will drive much needed increases in wages, but also higher energy costs,” he said via Twitter.

Sebastien Galy, a senior macro strategist with Nordea Asset Management, told CNN Business that ESG will drive prices higher. “The outlook for inflation is one that should stay elevated for the next 10 years due to ESG cost integration and a tight oil and natural gas supply.”

Lack of capital for energy production can create more than just a financial crisis. It’s causing shortages of food, minerals and the fertilizer that’s a byproduct of natural gas. Those shortfalls will impede the switch to alternative systems.

The public hasn’t witnessed the full impact of rising natural gas and oil prices just yet. Those price increases will probably raise the price of food in North Africa and the Middle East in the months ahead. The Global Food Price Index reached record levels in February, meaning that food costs are higher now than when they contributed to the unrest that touched off the Arab Spring in 2010.

On the energy front, the relatively mild winter of 2021-22 prevented what could have been catastrophically high heating bills in the U.S. and Europe. Yet the fundamentals don’t suggest that prices will be under control in 2022, let alone by 2025.

And despite widespread confidence that electric vehicles can capture meaningful market share by 2030, the cost of those vehicles continues to rise as oil and gas remain critical for mining, construction and delivery. Last year, lithium prices increased by more than 500%, while nickel has exploded because of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Large spikes in crude oil prices have preceded recessions dating back to the 1970s. Some analysts say the U.S. stimulus packages of 2020-2022, combined with suspending taxes in the future and passing “gas stimulus” bills will buffer the shock, but that thinking is based on a fundamental ignorance of economics.

Stimulus checks and reductions in gasoline taxes can increase demand, which raises prices and makes the need for those measures temporary. Asking citizens to burn less gasoline isn’t politically feasible.

Global energy markets face economic stress. A commodity super-cycle appears inevitable, and a reckoning could take a toll on the economy. History suggests demand destruction and a recession.

Will a conversation about stability and the real cost of energy sources occur before the economy reaches that point?

In the end, it’s fitting that BlackRock’s co-founder and president Rob Kapito offered a perplexing take in discussing rising prices and scarcity at a March conference hosted by the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association.

Kapito said the U.S. economy faced “scarcity inflation”—a combination of rising prices and shortages of oil, housing and agricultural commodities.

“For the first time, this generation is going to go into a store and not be able to get what they want,” he said. “And we have a very entitled generation that has never had to sacrifice.” He suggested that people should put on their seat belts for what lies ahead.

For what it’s worth, Kapito earned more than $20 million in compensation last year. At some point, that “entitled generation” will realize what is really driving prices higher. He might want to buy some adhesive removers if the “entitled” start gluing themselves to BlackRock’s doors.

It now appears BlackRock’s leaders, similar to many politicians, fail to understand the consequences of their policies.

Or worse, they celebrate higher prices in a misdirected effort to change human behavior.

A Traditional Energy Alternative?

While Blackstone Group might turn away from fossil fuel exploration and production, a rival appears poised to capitalize on significant dislocations of capital.

In December 2021, Crescent Energy Group (CRGY) dropped out of a deal between private equity firm KKR and Contango Oil and Independence Energy 2021. (This is not to be confused with Crescent Point Energy, trading under the ticker CPG).

Crescent Energy Group is managed by KKR’s Energy Real Assets team and led by David Rockecharlie, head of KKR Energy Real Assets. He’s the company’s chief executive officer and serves on the board of directors.

The company plans to grow by acquiring bargain-priced assets that can scale into cash flow machines. If oil goes the way of tobacco, expect rampant consolidation among managers who recognize the long-term demand and have skin in the game. Management owns 22% of the company and plans to maintain a low-leverage strategy.

Earlier this year, the company purchased Verdin Oil Co.’s assets in Utah’s Uinta Basin for $815 million. Analysts valued the assets at nearly twice the purchase price.

Anyone who buys this stock will not have a vote on the company’s direction. So, effectively, KKR, the PE firm, will elect the board and control the operations. However, that’s a positive thing because activist shareholders can’t force cash-starving policies into practice.

This isn’t a management team aiming to make 7% to 10% per year. There’s a triple-digit upside ahead and potentially far more, depending on market conditions and the value of future deals.

Garrett Baldwin is a commodity and trade economist who serves as Luckbox’s editor at large. He actively trades value and momentum stocks and wagers on sports and prediction markets.