Demystifying Mensa

Members of the best-known high-IQ society don’t just discuss Proust or quantum mechanics. They know other ways of having fun, too.

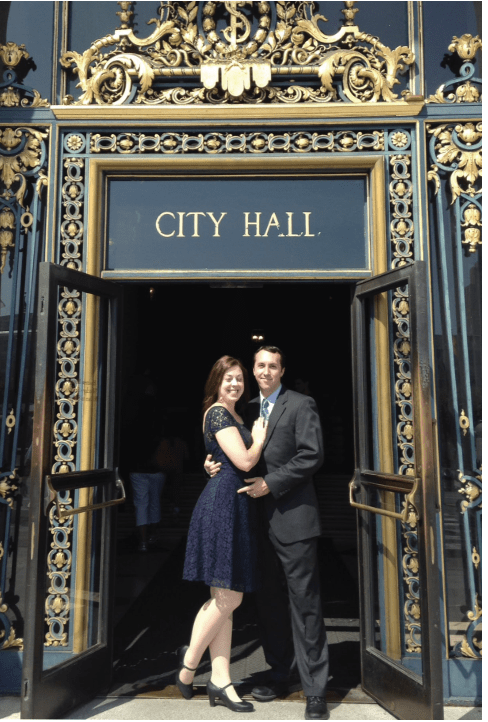

The leaders of Mensa, a society that brings together extremely intelligent people, espouse some lofty goals for the organization. But in a lot of ways it’s really a social club. Just ask Stephanie and Jameson Thornton, a couple whose courtship and marriage are intertwined with the Mensa experience.

Here’s how their relationship started. Jameson, a Mensan living in San Francisco, decided it might be fun to attend one of the organization’s weekend-long regional gatherings in Boston, a city he’d never visited. For Stephanie, a Boston Mensan, it was only natural to be at the meeting.

The two got acquainted at the gathering, finding they shared a competitive spirit as they bonded over board games. “He was willing to do Sudoku races with me, so I knew it was a good match,” Stephanie recalls, citing their mutual interest in the number-placement puzzles.

A long-distance romance ensued with Jameson and Stephanie a continent apart. Then they found themselves together again in Boston at one of Mensa’s annual national meetings. Jameson was competing in the Mr. Mensa pageant, and Stephanie was discharging her duties as a Mensa board member and volunteer official.

That’s when Jameson seized the opportunity to stage a classic event. Onstage, in front of hundreds of Mensa members, he went down on one knee to propose marriage. Stephanie accepted and six years later they’re living in San Francisco with their 3-year-old.

And there’s another twist to the story: When Stephanie met Jameson she was the widow of a man she’d also met at a Mensa event.

Like-minded companions

Not everyone who joins Mensa finds a life partner the way Stephanie and Jameson did, but many members do discover a comradery that’s lacking in their everyday interactions, says Charles Brown, American Mensa director of marketing and communications.

“Our members join for a number of different reasons,” Brown notes. “For some, it’s that social aspect. It’s just being around like-minded people. A lot of them found in their school experience and other experiences that they didn’t fit in.”

“Mensa members join for a number of different reasons. For some, it’s that social aspect.”

Without a peer group, people with high IQs can feel isolated or ostracized, notes Renee Lexow, American Mensa’s supervisory psychologist. Those feelings can lead to anxiety or depression, she says.

Stephanie Thornton—to use her in a second example—was experiencing that feeling of being alone when she began teaching school in Orlando, Florida. She didn’t know many people there and missed the group of honors students she hung out with in college. But that changed when she joined Mensa.

“I found a home,” Stephanie says of signing up for the organization. “Suddenly, I had a social life.” She began attending lots of the local organization’s events to play board games, go line dancing or frequent the Downtown Disney District. Soon, she began meeting up with members outside of the planned Mensa activities, too.

That wide variety of activities is typical, Brown observes. What Mensa members do when they congregate at the organization’s meetings can be serious (physics or anthropology), athletic (hiking or rock climbing) or festive (puzzles or trivia contests), he says.

Global reach

No matter how Mensa members choose to interact, they’re building upon an organization that began in England in 1946. The founders chose the name “Mensa,” which is Latin for “table,” because it suggests an image of members seated around a table, Brown says.

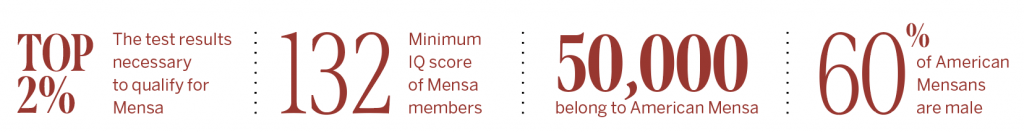

These days, Mensa International has 134,000 members in 100 countries. American Mensa has attracted more than 50,000 members, while British Mensa has signed up 21,000 and German Mensa has recruited 13,000.

American Mensa, which was started in 1960, has 130 or so local groups that organize weekly or monthly gatherings. Regional groups meet periodically, and a big national gathering occurs annually. Mensa is also divided into interest groups that explore about 125 different pursuits that vary wildly.

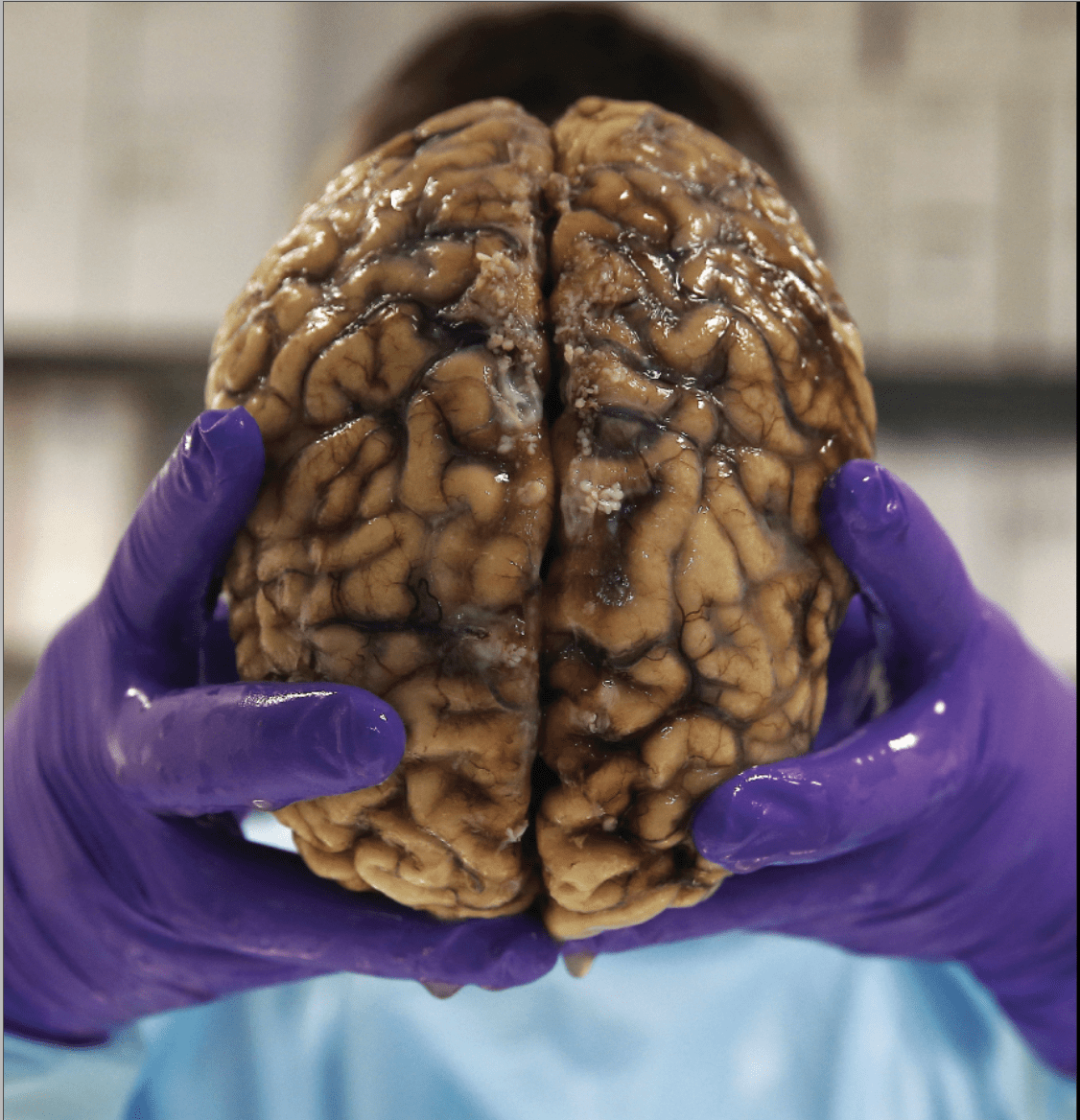

Besides all the fun, Mensa pursues three serious objectives outlined on the group’s American website. “Mensa identifies and fosters human intelligence, encourages research into the nature and uses of intelligence and provides a stimulating intellectual and social environment for members,” according to the site.

To achieve those goals, the Mensa Foundation works to inspire and empower giftedness for the benefit of society by presenting awards and scholarships and performing educational outreach and research, Brown says.

He notes that the Mensa constitution prohibits the organization from taking a position on any issue, but he adds that members have plenty of their own opinions to make up for that restriction.

Who joins?

That wealth of opinions springs from a diverse membership, Brown continues. “Our members are some of the most interesting people I’ve ever met in my life,” he contends. “That doesn’t mean they’re all successful. It doesn’t mean that they’re all goal-oriented. It just seems that they’re very curious, very intellectually fascinating people.”

Stereotypes don’t hold true for Mensans, according to Brown. “People hear that you have a high IQ and they think you probably walk around in a lab coat all day,” he says. “I don’t think that is a conclusion people can draw. It just means that you have a very curious, active, agile mind. And our members apply that in many different ways.”

Brown shared an anecdote that illustrates some members’ tendency to master one field and then move on to another to satisfy their curiosity. The story goes that the producers of a television quiz show contacted Mensa in their search for smart contestants. The organization contacted members, and one who replied said he had a bachelor’s in biology and a master’s in neuroscience but was driving a cab because he wanted to learn the craft of acting by meeting and observing people.

Some members join later in life, but others discover the organization at an early age, Brown says. “A lot of the educational system is just not set up to handle gifted youth very well,” he contends. “So, they tend to fall through the cracks.”

Who qualifies?

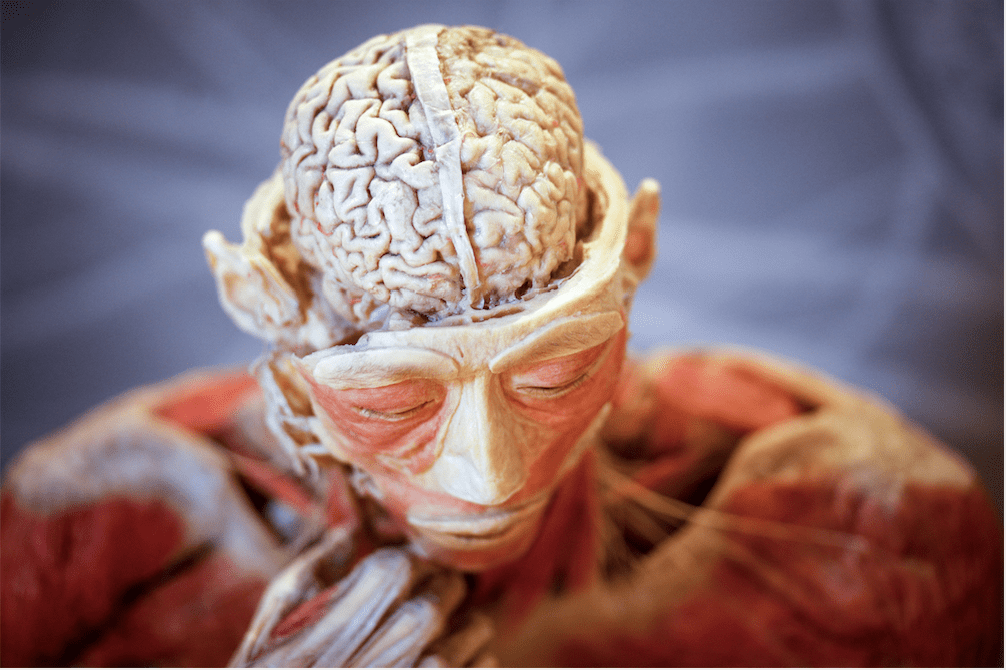

Anyone who places in the top 2% of the population on any test accepted by Mensa is eligible to join. That equates to an IQ score of roughly 132 on the Stanford-Binet test.

But Mensa offers its own test, too. Lexow, the American Mensa supervisory psychologist quoted near the beginning of this article, oversees the proctors who administer two-hour admissions tests owned by the organization.

She also determines whether other tests that candidates submit for admission qualify as valid. Mensa accepts some outside tests if they’re administered and scored by qualified testers, but it doesn’t admit prospective members on the basis of short online quizzes.

It’s a testing process that yields a group of people who share at least one trait, Brown maintains. “If I could generalize about our members,” he says, “it’s that they are just insatiably curious about everything.”