The face of the resistance

Author Danny Caine is raising Cain about the problems he says Amazon causes

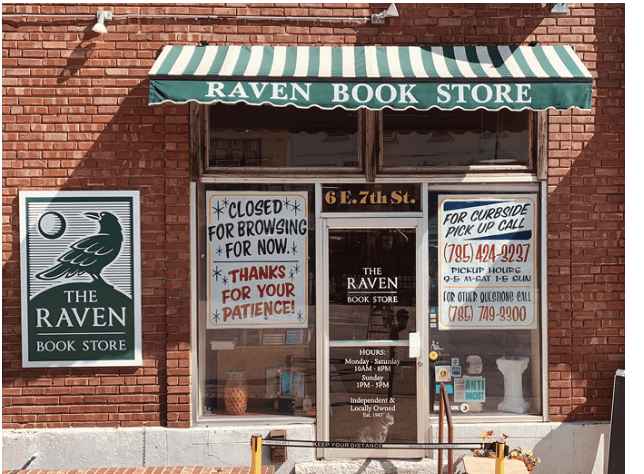

A lot of people complain about Amazon, but Danny Caine is doing something about it. Caine, a poet and the owner of The Raven Book Store in Lawrence, Kansas, is the author of the book How to Resist Amazon and Why. He sat down with Luckbox to detail what he sees as problems with the giant retailer and tech company.

How is Amazon different from other companies?

We’ve never seen a company quite as big that does quite as much. It started as a retailer and then expanded into a third-party online retail platform. Now, it’s into home security video surveillance and web hosting. I see a lot of parallels with Walmart and its rise in the ‘90s and its effect on small businesses. But from where I’m sitting, Amazon is a much bigger threat than Walmart ever was simply because of how big it is and how many things it has its fingers in.

Amazon sometimes sells at a loss. What’s the strategy behind that?

They look to catch customers in a flywheel. You get hooked into Amazon products, and you just keep spinning around within their ecosystem. You’ve got a Prime subscription so that’s where you get your video streaming and where you get your groceries. That’s where internet advertising is targeted to you, and the Ring Video Doorbell is owned by Amazon. You just keep spinning around that flywheel, and Amazon is collecting more and more data about you. That makes it easier and easier for them to extract money from you.

They also say they’re driven by customer obsession. That doesn’t mean they’re obsessed with customers—it means they want their customers to be obsessed with them. One way to get people onto the flywheel is with really cheap retail goods and shipping that’s very fast and appears to be free. So they’re selling a book at a loss. When I buy a hardcover book from a publisher for my store, I pay $15 and sell it for $26.99. Amazon might sell it for $10. They’re either getting a bigger discount from the publishers, which is a problem, or more likely they’re selling it at a loss. And that’s just to get people hooked in.

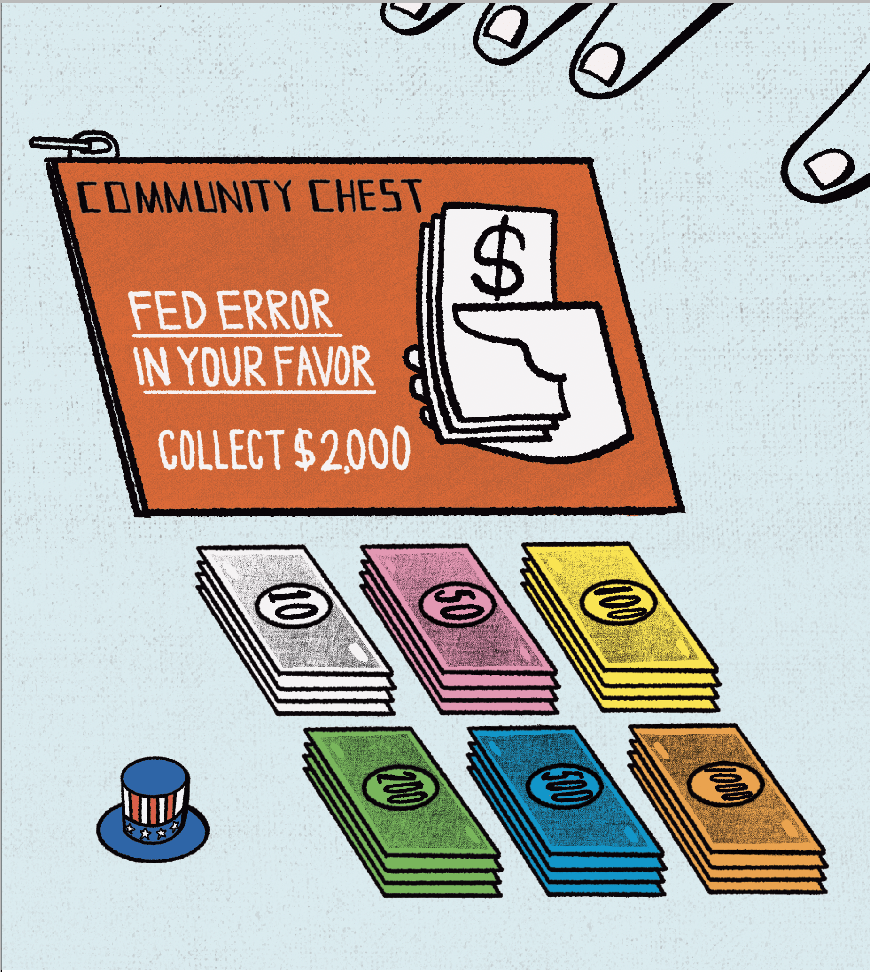

You’ve said that Amazon bends the rules of capitalism. How?

They’re selling at a loss to drive their competition out of business. That’s predatory pricing and it’s illegal. It’s also incredibly difficult to prove. The way government interprets antitrust law, the burden of proof for predatory pricing is extremely high, so it’s rarely prosecuted.

Amazon tried to buy Diapers.com, but Diapers.com refused to agree to a deal. So Amazon dropped all of its prices on competing products, and Diapers.com either had to go out of business or sell to Amazon. As soon as that was resolved, Amazon raised the prices.

How well does Amazon treat workers?

Well, this is a big one. Because Amazon is one of the most profitable companies in the world, other companies are going to look to Amazon for inspiration and tricks. They’re going to mimic the way Amazon handles jobs, which is not good.

They look to catch customers in a flywheel. You get hooked into Amazon products, and you just keep spinning around within their ecosystem.

Next-day shipping for Prime subscribers is built upon a huge network of fulfillment centers, and the workers in those centers are facing dangerous conditions. They’re pushed to incredible quotas and expected to maintain a pace they can’t hope to achieve. They’re working 12-hour shifts with the feeling that they can never catch up.

The grueling effect on mind and body makes Amazon fulfillment-center work twice as dangerous as warehousing industry peers, and Amazon workers are twice as likely to get injured as workers in other warehouses.

Amazon relies on third-party contractors for a ton of what they do. That provides a linguistic loophole: When they say employees get $15 an hour, they might not necessarily mean the third-party contractors. Many of the people driving those vans are third-party contractors who work for private shipping companies. But those private shipping companies have only Amazon as a client, and the owners started their companies with Amazon loans. The contractors’ employees are wearing Amazon shirts and driving Amazon vans, so they’re basically Amazon employees, but by calling them third-party, Amazon can escape responsibility for what happens in those vans, where those drivers can go to the bathroom or who gets injured when fatigued drivers hit people.

Amazon is putting us on the wrong track for worker rights in this country. When the workers try to unionize, Amazon resorts to extensive union-busting tactics. It successfully busted up a unionizing effort in Bessemer, Alabama, with a massive intimidation campaign against those workers.

Early in the pandemic, Christian Smalls was raising the alarm about coronavirus protections at the Staten Island Amazon fulfillment center where he worked. He was fired and scapegoated in that they tried to make an example of him. All he was doing was trying to make his workplace safer.

How does Amazon treat third-party sellers?

The average fee that Amazon extracts from those sales is 30%. As a small business owner, I can tell you that if I had to hand over 30% of every sale to my landlord, it would be unsustainable. We wouldn’t last more than a couple of weeks.

Amazon has its own legal system for appeals and discipline of third-party sellers. It’s notoriously punitive and capricious. There’s a whole industry of lawyers who work only with Amazon sellers trying to get their accounts back after they’ve been banned, often for silly reasons.

Amazon also has been caught stealing intellectual property and ideas from those third-party sellers to make their own store brand. Amazon is both the provider of the platform and a competitor on that platform. That allows them to collect data on these third-party sellers, determine which products are profitable and then create their own competing products.

What’s up with Amazon and the post office?

During its rise, Amazon was seen as a possible savior for the post office, and the USPS even renegotiated its union contract to allow Sunday delivery for Amazon packages. But at this point, it seems more like Amazon is trying to build its own competing version of the USPS.

It relies on the USPS to get merchandise to distribution centers, and then from the distribution centers Amazon last-mile drivers take them to that last stop on the journey. The USPS has a mandate to deliver to every address in the United States, but Amazon can look at a delivery and say, “Well, it’s too expensive for us to get there. We’re still going to make the USPS do this.”

Amazon packages going third and fourth class are getting prioritized over USPS Priority shipments. That means people were getting medications late. The USPS is getting pushed around by Amazon quite a bit.

What about law enforcement’s involvement with Ring Video Doorbells?

Amazon bought Ring after the product was developed, and they have turned police departments into a salesforce for this technology. One feature of the Ring doorbell is that you can share video from your doorbell with the police department. This is appealing to police departments because, like Amazon, the police are interested in collecting data.

It raises all kinds of privacy concerns like sharing video of someone without their consent with the police department. That’s a civil rights problem—a wealthy white person sits safely inside a home, sending video of a person of color to a police department that has a history of racist practices. It’s a dangerous game. Giving them that kind of access to all this surveillance is really frightening to me.

Another frightening thing is that Amazon is working hard to develop facial recognition technology. A couple of Amazon execs are hinting that they might merge facial recognition technology into Ring. If you’re in some database, and you walk in front of the wrong doorbell, you’re going to get your video automatically sent to a police department without your consent, triggering the facial recognition. Facial recognition technology works poorly on dark skin and frequently misidentifies people of color.

Is Amazon taking on some of the characteristics of a government?

It’s becoming a government unto itself. Amazon has its own postal service with its fleet of third-party delivery drivers. It has its own court with its third-party seller discipline system. It’s collecting taxes from those sellers at 30% per sale.

Amazon knows that the only limits to its power are the government and antitrust law enforcement. Jeff Bezos is building a mansion in Washington, D.C., and picked Arlington, Virginia, for the second headquarters. The current Amazon spokesman, Jay Carney, was the Obama press secretary. Amazon’s really concerned and making sure that the government is on its side.

The cozy relationship between the federal government and big tech is souring a little bit on both sides, which I see as a good thing. But local governments still love it when Amazon moves to their area and builds a fulfillment center or opens offices. But Amazon wants these humongous packages of tax breaks and corporate welfare. It won’t open a facility without that, so you’ve got municipalities and counties and cities bending over backwards. Elected officials are giving a free pass on taxes to this company for them to bring these dangerous, low-paying jobs to an area. That doesn’t seem like a great deal long-term.

It collects data on cities the same way it does with consumers. The cities invited to apply for HQ2 put together these giant packages of data and demographics and handed it over to Amazon for free. Many thought it was a foregone conclusion that it was going to pick New York and Washington, D.C., for the second headquarters, and ultimately it did. But now they have all this great, super-valuable data about 400 cities and how much exactly those cities are willing to give over in tax breaks for Amazon to open up there. It was just another data-collection scheme.

What can people do to resist all this?

The individual consumer is welcome to boycott Amazon if that’s their choice. But Amazon is so big, I’m not sure that that’s the best strategy for successfully resisting it. It isn’t going to feel one person canceling a Prime subscription.

Leaning on the government is really important. Be in communication with your elected officials about these issues and about changing the way antitrust laws are enforced.

Support the small businesses that are building your community—doing the work that Amazon isn’t interested in. A bookstore, an organic co-op or a stationery store, a record store is going to feel the addition of a new regular customer.

What actions are the government taking?

Lina Khan has been nominated as commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission, which is a huge deal. She’s a leading architect of this nascent antitrust movement, a super-influential thinker and a harsh critic of Amazon and big tech. To have her in a position like FTC Commissioner is an important sign of progress in reining in big tech and these monopolies. At her confirmation hearing, she drew kind words from both sides.

The left and the right hate big tech for different reasons. When bipartisanship is so rare, I am encouraged to have both sides similarly irritated by this monopoly power. That might be an indication something will happen.