The Real Threat of Deepfake

Videos of events that didn’t really happen can overturn elections and sabotage companies

The pornography industry latches onto new ideas quickly, particularly when it comes to technology. Porn pioneered internet-based video streaming services a year before CNN and a decade before YouTube. But porn’s latest foray into technology could be as disturbing as it is disruptive.

For decades, graphics geeks and the digital literate have been using platforms like Adobe Photoshop and After Effects to alter photos and videos. They do it to promote a cause, advertise a business, campaign for a politician, get a laugh with a visual gag or put a celebrity’s face on a porn star’s body. Until recently, the process required specialized skills and took considerable time, and the results were obviously fake. Anyone could tell with the naked eye that the images were doctored.

But that’s changing. Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is lowering the cost of fake videos, reducing the time it takes to make them and eliminating the need for special skills to manipulate the digital images. At the same time, the fakes are reaching a level of realism that tricks the eye and the mind. Take the example of fake videos of politicians delivering speeches. Viewers feel they’re seeing and hearing the candidates say things they have never really said.

It’s happening because AI captures facial characteristics from thousands of images and puts them together to create a video that’s totally convincing. Welcome to the world of deepfakes.

The term (a mashup of deep learning and fake) and its underlying technology achieved notoriety when a Reddit user whose handle was deepfakes published a series of real-looking fake celebrity pornographic videos in 2017. Fake found a new forum and, with the speed of Moore’s Law, deepfakes are becoming the latest existential threat to political, cultural and privacy norms.

The threat of deepfakes has already expanded beyond victimizing female celebrities in fake pornography. It’s moved into corporate espionage, market manipulation and political interference—presenting a grave new challenge for the Authentication Economy.

Last May, Florida Senator Marco Rubio warned the U.S. Senate Intelligence Committee that bad actors could use deepfakes to launch “the next wave of attacks against America and Western democracies.” Political operatives might throw the 2020 presidential election into chaos by creating a digital “October surprise” that could go viral before it’s detected as fake, he said.

In October, California became the first state to criminalize the use of deepfakes in political campaign promotion and advertising. California’s law is aimed at political attack ads placed within 60 days of an election.

But the concern is global. In mid-December, China announced that its Cyberspace Administration would enforce new laws that ban publication of false information or deepfakes online without disclosure that the post was created with AI or virtual reality (VR) technology.

Big tech platforms are stepping up as well. While Twitter has been drafting a deepfake policy, some insiders believe the company’s decision to ban all political advertising stems from a video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that was altered to show her slurring during a speech. The video went viral, underscoring the platform’s vulnerability to doctored content.

In September, Facebook (FB) donated $10 million in grants and awards to the Deepfakes Detection Challenge, which was established “to spur the industry to create new ways of detecting and preventing media manipulated via AI from being used to mislead others.” Partners in the Challenge, which will run through 2020, include Microsoft (MSFT), Cornell Tech, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Oxford and University of California at Berkeley.

As government and tech firms step up to meet the impending threat, deepfake dissemination is expanding beyond the bounds of pornography, notes Giorgio Patrini, the Authentication Economy tech entrepreneur who founded Deeptrace, a deepfake detection platform. (See “The State of Deepfakes.”)

Some fear that policing and detection won’t keep pace with the technology’s rapid development. In fact, deepfake pioneer Hao Li, associate professor of computer science at the University of Southern California, recently predicted that manipulated videos that appear “perfectly real” will be accessible to all in less than a year.“It’s going to get to the point where there is no way that we can actually detect [deepfakes] anymore,” he said. “So we will have to take a look at other types of solutions.”

The State of Deepfakes: Landscape, Threats and Impact

By Giorgio Patrini

The rise of synthetic media and deepfakes is forcing society toward an important and unsettling realization: The historical belief that video and audio are reliable records of reality is no longer tenable.

Until now, people trusted that a phone call from a friend or a video clip of a known politician was real because they recognized the voices and faces. People correctly assumed that no commonly available technology could have synthetically created the sound and images with comparable realism. Videos were treated as authentic by definition. But with the development of synthetic media and deepfakes, that’s no longer the case. Every digital communication channel our society is built upon—audio, video or even text—is at risk of being subverted.

The deepfake phenomenon is growing rapidly online, with the number of deepfake videos almost doubling over the last seven months to 14,678. Meanwhile, the tools and services that lower the barrier for non-experts to create deepfakes are becoming common. Perhaps unsurprisingly, web users in China and South Korea are contributing significantly to the creation and use of synthetic media tools used on the English-speaking internet.

Another trend is the prominence of non-consensual deepfake pornography, which accounted for 96% of the deepfake videos online. The top four websites dedicated to deepfake pornography received more than 134 million views on videos targeting hundreds of female celebrities worldwide. This significant viewership demonstrates a market for websites creating and hosting deepfake pornography, a trend that will continue to grow unless decisive action is taken.

Deepfakes are also roiling the political sphere. In two landmark cases from Gabon and Malaysia that received minimal Western media coverage, deepfakes were linked to an alleged government cover-up and a political smear campaign. One of the cases was related to an attempted military coup, while the other continues to threaten a high-profile politician with imprisonment. Seen together, these examples are possibly the most powerful indications of how deepfakes are already destabilizing political processes. Without defensive countermeasures, the integrity of democracies around the world is at risk.

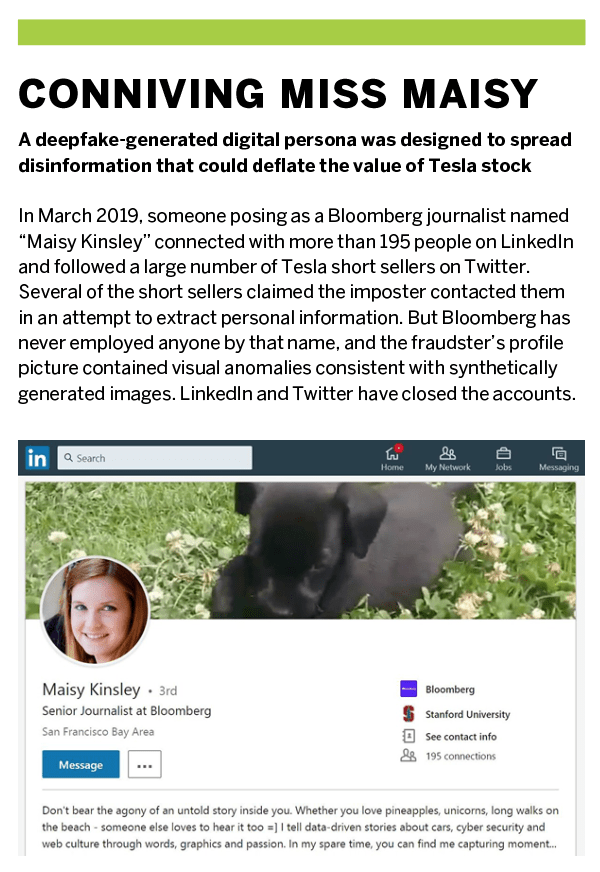

Outside of politics, the weaponization of deepfakes and synthetic media is influencing the cybersecurity landscape, making traditional cyber threats more powerful and enabling entirely new attack vectors. Notably, 2019 saw reports of cases where synthetic voice audio and images of non-existent, synthetic people were used in social engineering against businesses and governments.

Deepfakes are here to stay, and their impact is already felt on a global scale. Deepfakes pose a range of threats, many of them no longer theoretical.

Conclusions on the Current state of deepfakes:

• The online presence of deepfake videos is rapidly expanding and most are pornographic.

• Deepfake pornography, a global phenomenon supported by significant viewership on several websites, targets women almost exclusively.

• Awareness of deepfakes is destabilizing political processes because voters can no longer assume videos of politicians and public figures are real.

• Deepfakes are providing cybercriminals with sophisticated new capabilities for social engineering and fraud.

Giorgio Patrini is Founder, CEO and Chief Scientist at Deeptrace @deeptracelabs