This CBD Manufacturer Welcomes Oversight but with a Caveat

Regulators should not limit the public’s access to the THC-free cannabinoid, a CBD entrepreneur says

Federal regulation could ensure the purity, potency and effectiveness of CBD products while curbing the industry’s unfounded medical claims, overzealous marketing and false advertising. But regulators should stop short of imposing requirements that limit the public’s access to the relaxing benefits of CBD tinctures, ingestibles and topical agents.

Those are the thoughts of CBD entrepreneur and advocate Amy Duncan, founder and CEO of Mowellens, a firm she refers to as “a conscious CBD wellness company.” Duncan doesn’t take those positions lightly. She arrived at them after working in the medical device and biotech industries, studying the business side of the American healthcare industry, caring for a spouse stricken with brain cancer, and observing her spouse’s dutiful acquiescence to Western medicine.

Oversight by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) could include third-party lab testing to ensure the purity of CBD products, Duncan says. “The harm that we see comes when CBD is synthetically derived, when it’s riddled with solvents, pesticides, microbials and heavy metals,” she asserts. “There’s risk when you’re dealing with a dirty product.”

Duncan finds herself on an email list of about a hundred CBD industry players who receive messages from China bearing an iPhone image of a jar of CBD oil shot against a background that provides no sense of where the picture was taken. “It’ll say honey-cut CBD oil, $700 a kilo,” she recalls. “And that’s far below the price point in the U.S.”

The email message doesn’t provide a clue as to where the hemp was grown, who grew it or what additives have been introduced, Duncan complains. “It’s just scary,” she exclaims. “People have to make an ethical decision about whether they’re in this industry for the right reasons or if they’re just in it to make money.”

In contrast to the uncertainty of that offer, Duncan works closely with a hemp farm that tracks its product religiously. She even prints a QR code on her CBD product packaging that customers can scan to view a Google Earth snapshot of the row where the hemp was grown.

Besides demanding purity, the FDA could also ensure that marketers don’t make claims that aren’t substantiated by scientific research, Duncan says. “The packaging and labeling claims that we see put accessibility, the wellness industry and CBD in jeopardy,” she notes.

Regulations already ban marketers of herbal or dietary supplements—such as CBD—from claiming their products diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any illness, Duncan says. That means purveyors of CBD products should not make promises on labels or websites about reducing inflammation, anxiety and depression, she maintains. Failing to staunch such claims could result in strict regulation, she fears.

Inspiration in Adversity

Amy Duncan, who went on to become CEO of Mowellens, a CBD products company, was studying at the University of Missouri at St. Louis in 2007 when she met her future husband, Chris Duncan. He was playing left field and first base for the Cardinals, who were then the world champions. He was also willing to dance to the Cupid Shuffle. They were married in 2011.

The next year he was diagnosed with brain cancer. But the surgery and chemo seemed to work,

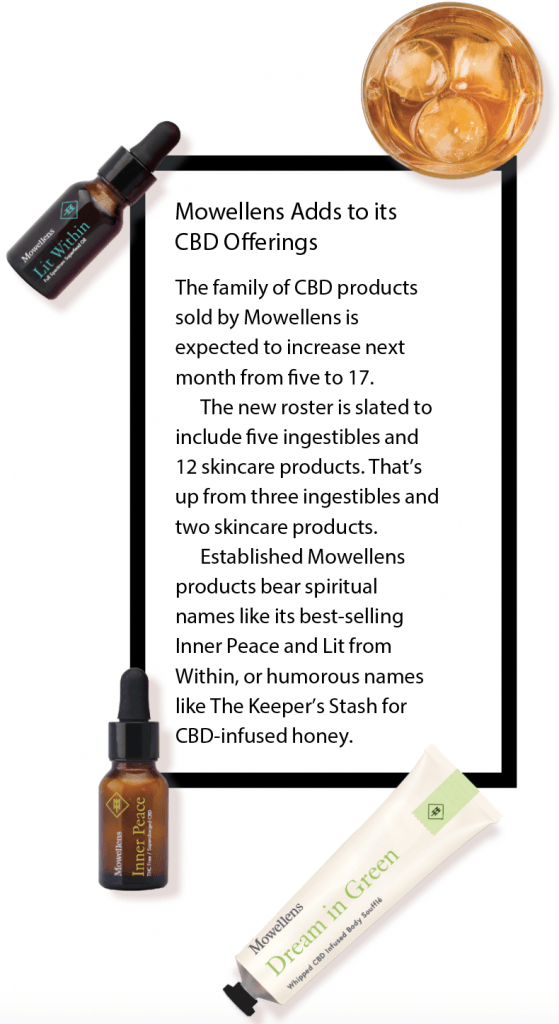

So she decided to take a giant leap in 2016. She quit her sales and marketing job at a biotech company to start Mowellens, a provider of CBD-infused

Then in October of that

Broad marketing claims also cause problems because not everyone reacts to CBD the same way. Duncan takes CBD in the middle of the afternoon to stay productive, while someone else might take the same dose to fall asleep at night. “I hate to paint a false hope for people,” Duncan says of making CBD promises that may not come true. “We like for people to experience it themselves, knowing that they’re not in harm’s way and that they can ask questions,” she says.

At any rate, prohibitions on medical claims could end as clinical studies explore CBD’s effects, Duncan says. Anecdotal evidence supports some of the claims and studies could back them up. So far, research into the endocannabinoid system—which regulates some the body’s processes and contains receptors sensitive to THC and CBD—has remained scarce because of the stigma attached to cannabis.

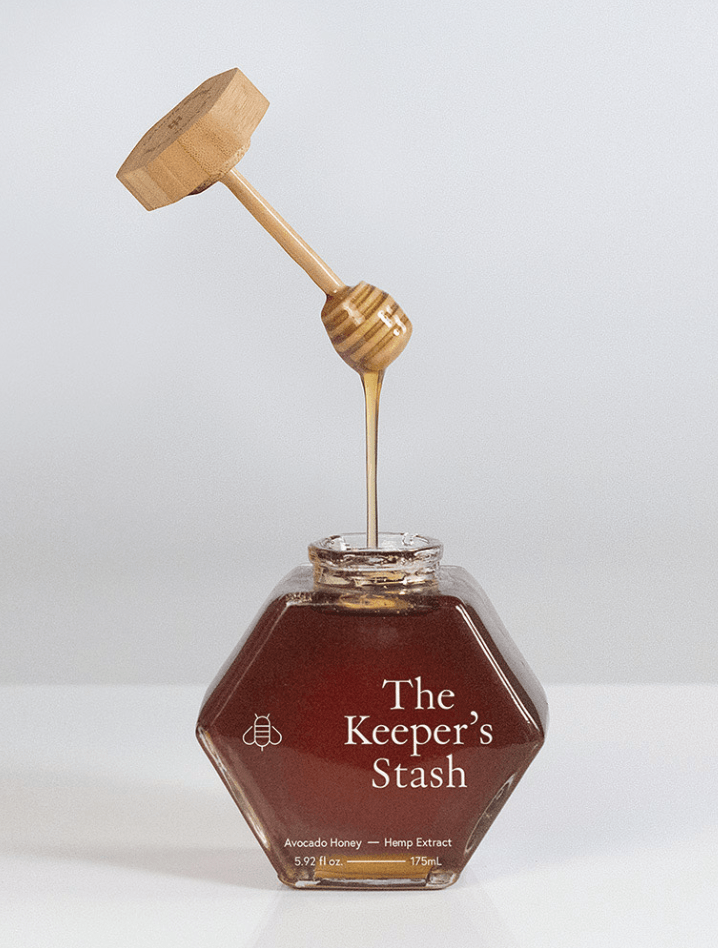

In the meantime, Duncan has found ways of conveying what she views as the benefits of her products without resorting to medical terminology. “It has a very calming, relaxing impact on the body and allows you to handle the stresses of day-to-day life,” she says. “It also any can help with any areas of the body that can hold tension. I call it meditation in a bottle.”

That brings Duncan to the topic of spirituality and CBD. “When it crosses into ethical questions associated with the industry, it crosses into morals and values of the leaders who are operating and trailblazing this industry,” she says. Many CBD entrepreneurs are women working to do the right thing, she concludes.

“The reason I entered the industry is this personal journey I had been on,” Duncan says. “I wanted to return to balance, provide for my family, and have flexibility and freedom.” When she made the decision to pursue freedom, all the elements of her life aligned.

“I know this is where I was meant to be.”

That passion makes Duncan worry that the FDA might go too far if it begins to oversee the CBD industry. If the agency demands the extensive clinical trials required for new pharmaceuticals, it could block the public’s access to CBD for a long time. Instead, she’d prefer the FDA assign CBD to “both lanes,” treating it as both a pharmaceutical and a dietary supplement. That way, the industry could continue to help customers, Duncan says.

Mowellens CEO Amy Duncan sent

Endocannabinoid: Receptors in the body’s endocannabinoid system react to the cannabinoids in cannabis and hemp. The receptors find a home in the brain, organs, connective tissues, immune cells

Pharmacogenetics: The study of inherited genetic differences in drug metabolic pathways is called pharmacogenetics. It identifies an individual’s therapeutic and adverse reactions to substances—such as CBD. Thus it explains why CBD affects individuals differently, or perhaps not at all.