Breaking Bad: Banks & Bailouts

As the pandemic forces more borrowers into default, banks might start failing.

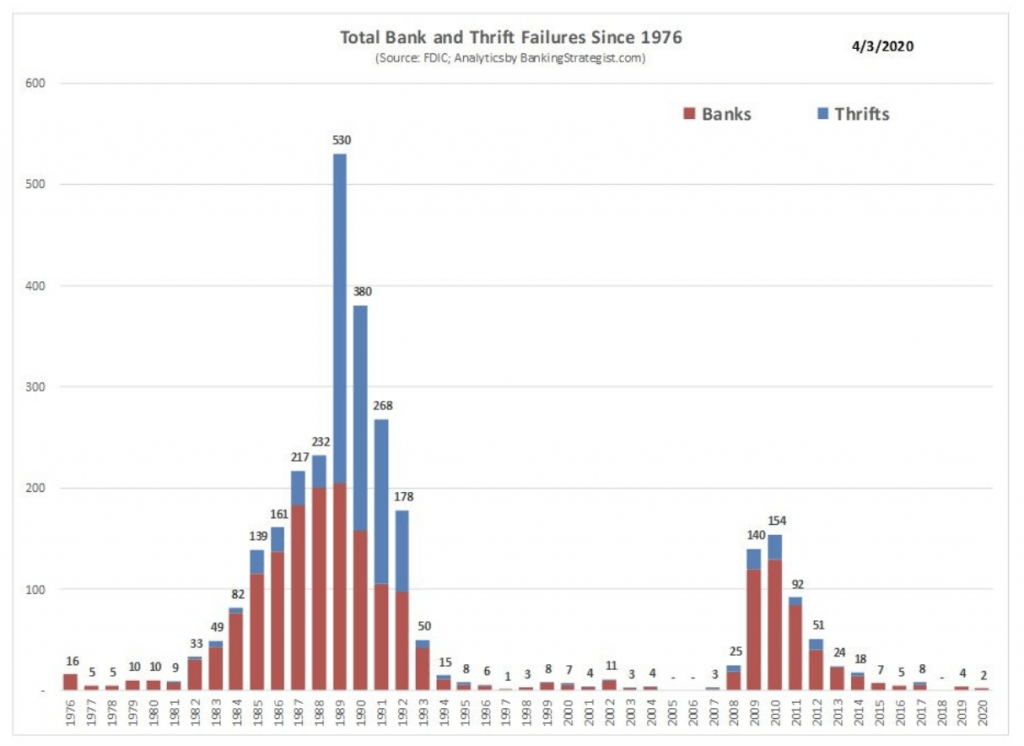

The Great Recession (2008-2009) caused the most bank failures since the Savings and Loan Crisis (1980s to 1990s). The years 2007-2011 saw 424 bank failures in the United States. By comparison, four failed in 2019. So far in 2020 there have been two.

Of course, the pandemic may not force the widespread failure of banks. During the dot-com bubble, which burst in 2000, only 30 banks went bust.

That’s because the dot-com bubble consisted of an economic recession and a severe stock market correction. In contrast, the Great Recession featured a “financial crisis” to go along with the other two.

Like a rusty anchor, a slew of undercapitalized banks paralyzed the financial system in 2008-2009. Billions of future U.S. taxpayer obligations (i.e. bailouts) were needed to grease the wheels to get things humming again.

In 2020, the situation has not yet devolved into a full-blown financial crisis.

So far this year, the stock market correction has come and gone (for now), and an economic recession seems to be intensifying. But the financial system has not yet buckled. Aggressive support from the Federal Reserve and Congress have clearly eased the burden.

But Q2 earnings reports released by the American banking sector suggest that things are likely to get worse before they get better.

Bank earnings in Q2 were down significantly compared with the same period last year, but at least they were still profits instead of losses. For example, net income for JPMorgan (JPM) fell by 51% in Q2 2020 compared with the same quarter last year—from $9.7 billion to $4.7 billion.

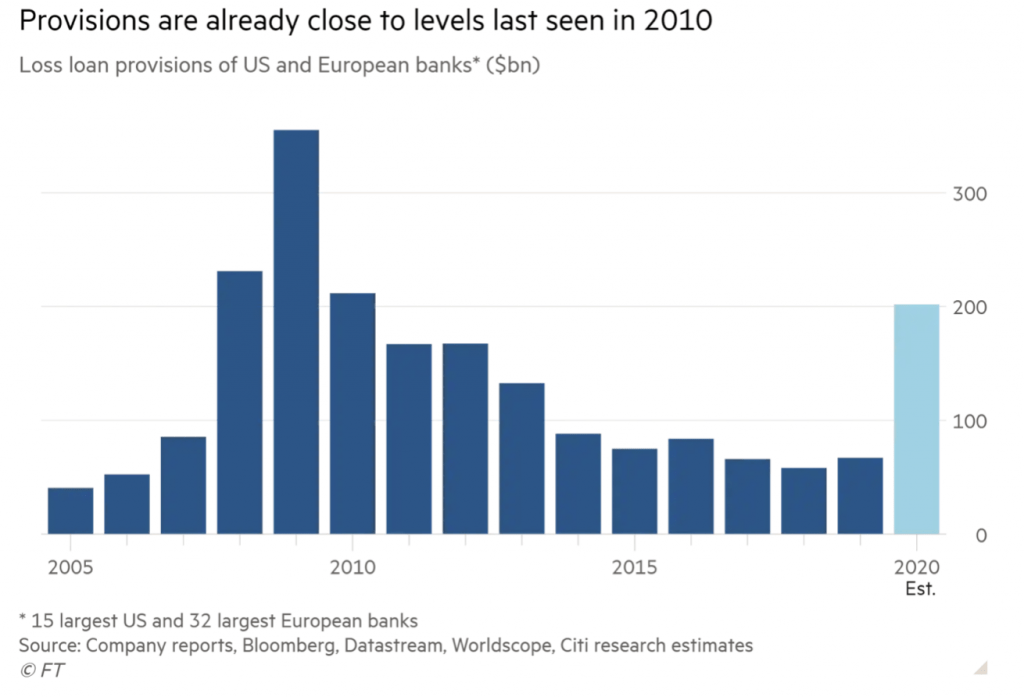

Aside from big declines in profits, earnings reports from the banking sector also seemed disheartening because of significant increases to “loan loss provisions.”

When financial institutions expect a rash of loan defaults, one of the first actions they take is to inflate loan loss provisions. In accounting parlance that means the banks set aside extra capital to cover expected funding deficits caused by bad loans. These are projected figures for future non-performance and aren’t guaranteed—meaning actual losses could be higher or lower.

As shown below, loan loss provisions at the largest banks in the U.S. and Europe have crept back up recently to levels not seen since 2010 in the aftermath of the Great Recession.

While the increase in loan loss provisions is troubling, banks haven’t yet started cutting dividends, which can also signal that trouble lies ahead.

Theoretically, American financial institutions are better positioned to weather a severe economic downturn in 2020 compared with 2008. That’s mainly because of stronger government regulation and oversight enacted after the last crash, commonly referred to as the “Dodd-Frank Act.”

Banks and other financial institutions are now subjected to regular stress tests to ensure they possess the capital necessary to make good on potential liabilities and to weather troubled waters.

That’s the theory anyway—whether it holds is another matter.

If the banks do run aground in the coming months, their troubles will likely stem from Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs).

CLOs are a close cousin of the Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) that became famous during the Great Recession. CDOs are financially engineered products that essentially repackage consumer loans into groups, called tranches. The problem is that it’s a lot easier to hide blemishes in a group.

CDOs combine high-quality, middle-quality and low-quality borrowers, and when the economy tanke, so too did the performance of the loans—especially the loans made to lower quality borrowers. That’s the whole “subprime” thing.

Unlike CDOs, which are linked to individual borrowers, CLOs are a form of corporate debt.

With the extremely low interest rates of the last decade, American corporations took down a historic amount of “cheap” debt. Last year, corporate debt rose above $10 trillion, or nearly half of the annual GDP of the United States—a record.

And just like the borrowers in the mortgage and credit card sectors, some corporate borrowers are less reliable than others.

Therefore, one huge outstanding question is whether CLOs will hold up better than CDOs if things go upside down again amidst the corona crisis. That may be the reason the Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLF) is still down 20% this year.

When the CDO scheme unraveled in 2008, the American economy was forced to its knees. The only reason that the Great Recession didn’t turn into a second Great Depression was taxpayer-funded bailouts of the financial industry.

If businesses continue to drop like flies in 2020, and bank profits are squeezed further, there may be a reckoning for CLOs. Should that come to pass, a rise in bank failures seems inevitable—not to mention another taxpayer bailout.

But with the national debt expected to grow by $6 trillion in 2020, what’s another trillion, give or take?

To follow everything moving the financial markets, readers may want to tune into TASTYTRADE LIVE weekdays from 7am to 3pm Central time.

“Sage Anderson” is a pseudonym for a contributor who has traded equity derivatives and managed volatility-based portfolios as a prop trading firm employee. He is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated company. Readers may direct questions about this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.