Trading the Escalating Trade War

Prior to 2020, the United States and China were embroiled in a trade war that made relations between the world’s two largest economies thorny, at best.

Developments in the current calendar year, mainly as a result of the spread of COVID-19 out of China, have added a new layer of complexity to a relationship that appears to be deteriorating by the passing of every new day.

But one interesting contrast to rising tensions is that the national stock markets of the U.S. and China have both rebounded in somewhat astounding fashion in recent weeks, despite the fact that the coronavirus pandemic continues to dampen global economic growth.

Looking at the iShares China Large-Cap ETF (FXI), one can see that it bottomed in 2020 on March 19 at about $34/share, down roughly 24% from its 2019 highs. As of June 1, the FXI has rallied 15% from there and is currently trading about $39. The 52-week high in FXI is just over $45.

The U.S. stock market took a more severe hit when COVID-19 started spreading in American cities but has also fought back in impressive fashion. The SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) was down about 34% at its low point during the coronavirus crisis (so far) and is now only 10% off the all-time high of $339 observed in late February 2020.

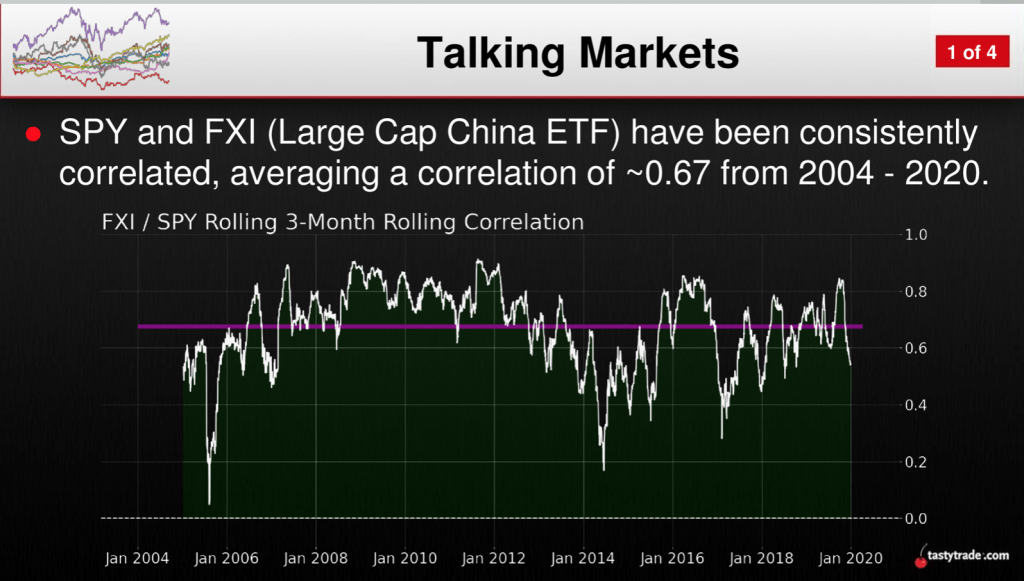

Notably, the SPY and FXI have consistently exhibited a positive correlation, which is by no means insignificant, as illustrated below (2004-2020):

Adding to the above data, the correlation between SPY and FXI rose to 0.87 during the most recent coronavirus correction, moving roughly 30% higher than the historical average.

Outside of stock market performance, one group of data that seems to mirror the negativity in rhetoric between the two countries is the economic data coming out of both regions. It’s believed that the unemployment rates in both America and China could be as high as 20% right now—even if the latter hasn’t admitted publicly the extent of the current downturn.

And beyond economic tensions already simmering due to the trade war, recent actions appear to have pushed the conflict into new areas—a reality that is derailing hopes that a truce (or at least a stalemate) between the two countries could be agreed upon in the near term.

One current flashpoint is the territory of Hong Kong, which is a part of China under the informal “one country, two systems” arrangement. When Hong Kong was passed back to mainland China by the United Kingdom in 1997, it was agreed upon at the time that Hong Kong would continue to govern itself in quasi-independent fashion for the next 50 years.

After that time, China was expected to assume more active leadership over the territory and possibly even fully integrate it with the mainland. Global investors initially cheered the agreement because it meant Hong Kong’s status as a global financial hub would remain intact, for at least the foreseeable future.

It’s that unique status that is now arguably in jeopardy.

Last year, new governance was considered for Hong Kong that was perceived to threaten the quasi-independent status enjoyed by the territory, and in response, many Hong Kong citizens took to the streets to protest perceived interference by the Chinese government.

While the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted that protest movement, it reignited recently when China announced it was instituting new laws in Hong Kong that are perceived to limit the freedoms of Hong Kong citizens further.

Although Hong Kong is technically a part of mainland China, the terms of the Hong Kong Policy Act (1992) stipulate that the U.S. may treat Hong Kong as distinct from the mainland when it comes to economic relations. This means in practice that a different set of rules applies to Hong Kong as compared to the balance of China, particularly when it comes to export controls, customs and immigration.

The ongoing nature of that “special consideration” is reaffirmed annually by the American government based on the perceived independence of Hong Kong from the mainland.

Last fall, American legislators passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act in response to the deterioration of Hong Kong’s perceived independence from the mainland which dictates that a more thorough official assessment must be conducted before the annual certification is decided.

On May 29, 2020, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that based on the current Hong Kong assessment, it was his belief that the territory was no longer sufficiently independent. Pompeo further implied that the annual certification would not be confirmed.

At this stage, it is not known exactly what might happen next, as to whether certain components of Hong Kong’s special status may remain, or whether the special relationship between the United States and the territory could be scrapped altogether.

One certainty is that the Chinese government will likely not be pleased with continued interference in its internal affairs, relating to Hong Kong or otherwise—a sentiment that may affect their willingness to negotiate further on outstanding trade issues.

Exacerbating the situation is the fact that President Donald Trump has been “saber-rattling” over potential retribution against China as a way of holding the nation “accountable” for COVID-19. The Hong Kong certification process, which appears in jeopardy, might be a part of Trump’s wider plan to “punish” the mainland.

And if all of that weren’t bad enough, it appears a new “front” in the U.S.-China dispute has been opened up, and one that has directly ensnared international financial markets.

Beyond disagreements involving economic (trade war) and diplomatic (Hong Kong) items, the new focus has been on listings of Chinese companies on U.S. exchanges, as well as American investments in China.

On May 20, the U.S. Senate passed the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which is focused on increasing scrutiny of all foreign companies on American exchanges but appears specifically geared toward China. Under the new law, foreign companies must disclose whether they are primarily owned by foreign governments, as well as adhere more strictly to American auditing standards when releasing financial data.

The catalyst for this legislation, beyond the trade war, can easily be tied to the recent stock performance of Luckin Coffee (LK), a Chinese firm listed on the Nasdaq. LK lost 95% of its value recently after admitting that certain aspects of its financial disclosures were falsified, including fake transactions that artificially boosted the company’s earnings.

Luckin had raised over $500 million in an initial public offering (IPO) on the Nasdaq exchange in May of 2019, meaning U.S. investors were directly affected by the falsified financial data and ensuing equity crash. It’s believed that the Luckin situation represents only the tip of the iceberg in terms of foreign companies trading on U.S. exchanges which may not be complying with the stringent auditing standards of their American-based counterparts.

While the new legislation should help protect American investors going forward, it could also affect America’s status as one of the preeminent places to raise capital. It’s been reported that the Chinese government is now encouraging mainland companies to target English exchanges (i.e. London) when pursuing future foreign IPOs.

In the same vein, it also appears the American government is seeking to disincentivize U.S. investors from purchasing mainland Chinese shares, too—yet another flashpoint in the broader campaign. On May 12, President Trump and the U.S. Labor Department directed a board in charge of investing federal pension savings to halt plans to invest in Chinese companies.

Taken together, these steps clearly illustrate that new fronts are opening up in the wider U.S.-China dispute, which may mean the “trade war” characterization is much too limited.

The fact that President Trump recently moved once again to limit the sale of American technology to Chinese technology giant Huawei is yet another signal that any real de-escalation between the countries will have to wait until well after the November presidential election.

And while the Chinese stock market may be performing relatively well at the moment, the Chinese currency (renminbi or yuan) has weakened sharply in value, which is almost certainly linked to the aforementioned actions taken by the United States government.

Prior to 2020, the Chinese yuan had already broken through the psychological barrier of 7.00 per dollar and has now dipped all the way down to 7.20. Technical analysts have suggested the yuan could drop as low as 7.40 in the near future, which would be its lowest level against the dollar since 2007.

Because the world imports so much from China, the recent move in the yuan may actually be a partial catalyst for the rally in Chinese stocks. A cheaper yuan versus a basket of international currencies means that Chinese imports are actually cheaper, which can provide a boost to Chinese manufacturers.

However, that also means that imports into China, of foreign goods, get relatively more expensive.

In terms of the so-called “Phase I” deal that was signed at the start of 2020, expectations are plummeting that any real progress will be made on reducing the infamous trade deficit between the United States and China. Multiple media outlets have reported how the Chinese are well behind on growing their purchases of American goods in 2020, as shown below:

In sum, the above likely means that whenever the coronavirus story does move off the front page of the financial pages, it will quickly be replaced by fracturing U.S.-China relations. Interestingly, it was this latter story that catalyzed a deep stock market correction at the end of 2018, similar in degree to the one observed in February/March of 2020.

With so many developments in the ongoing relationship between the world’s two largest economies, it’s possible that investors and traders may find potential opportunities in the financial markets multiplying in the coming weeks.

For more information on the relationship between American and Chinese markets, readers are encouraged to review a recent installment of Tasty Extras on the tastytrade financial network.To monitor ongoing market developments, readers can also tune into TASTYTRADE LIVE weekdays from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Central Time.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.