What May Drive Forward Gold Prices? Look to Oil for Clues

The financial world learned for the first time this week that the value of a crude oil futures contract can trade in negative territory.

One can say without reservation that particular lesson was learned the hard way.

The complication, as most are already aware, is that global lockdowns associated with the coronavirus outbreak produced a historic cratering in the demand for crude oil.

A world economy that previously consumed about 100 million barrels of crude oil per day, now needed only 70 million, or less. And cutting a mere 10 million barrels from daily supply, as OPEC+ did recently, still meant the world was awash with extra crude.

Given those supply and demand dynamics, the price of crude had to move lower. And while the crude oil market has been subject to its fair share of volatility during the last couple of decades, the fact that oil futures went negative was a fairly big surprise to everyone involved.

Certainly, the sudden, steep dropoff in demand was the catalyst for pushing prices to multi-decade lows. But what pushed oil prices into negative territory ultimately came down to the global capacity for crude oil storage, or lack thereof.

With the world consuming only 70 million per day (and OPEC claiming to cut 10 million), that left 15-20 million barrels on the open market that had to go somewhere. And somewhere quickly transformed into anywhere – particularly the huge ocean tankers that normally shuttle oil between suppliers and consumers.

As with the last major financial crisis, energy traders have been renting crude oil tankers to hold “black gold” during this period of depressed prices, hoping to sell it down the road for a profit.

But the supply of ocean-based tankers isn’t endless, and neither are land-based storage facilities. It’s believed that the total global storage capacity of crude oil is somewhere around 6.8 billion barrels, and of that, it’s estimated that less than 40% is still available.

However, those figures don’t account for regional bottlenecks.

One of the primary US hubs for crude oil storage, in Cushing, Oklahoma, is now only about 20 million barrels away from being filled to capacity. It also happens to be one of the storage depositories for the physical oil that underlies crude futures contracts.

The new oil rush in the United States leveraged fracking technology to push the country’s daily output to north of 12 million barrels per day in 2019, which placed it in the top several producers of oil on the entire planet (including Russia and Saudi Arabia). That level of production also means that the Cushing facility could be full in the very near future, unless a drastic cut in domestic production is enacted, or other storage plans are devised.

Regardless, the above circumstances meant that investors planning to take delivery of crude oil at the end of April, after the expiration of the most recent month’s futures contract, had very few options on where to put it.

The end result was that oil traders expecting to take delivery of crude oil were forced to unload those contracts – and price discovery was needed to figure out where along the continuum they would be relieved of their burden.

That price turned out to be below zero, to the tune of about negative $40/barrel, and thus, negative oil futures were born on US soil.

The continuing problem is that the global coronavirus lockdown (even if haphazard) isn’t expected to end anytime soon. And when it does, it will likely be done in planned phases.

With global storage trending toward “full,” that meant that as soon as the current month’s crude oil futures contract expired, energy traders immediately started pressuring the next month’s contract, too—and the month after, and the month after (albeit to lesser degrees).

The June delivery month for crude oil futures dropped 43% this past Tuesday, which put the price/barrel at $11.57. Prices for June delivery did recover slightly on Wednesday and Thursday, rising back above $16/barrel.

Crude oil volatility, measured by the OVX, hit a new all-time high on April 20, and then again on April 21, when it closed above 300. For context, the OVX traded below 40 for most of 2019.

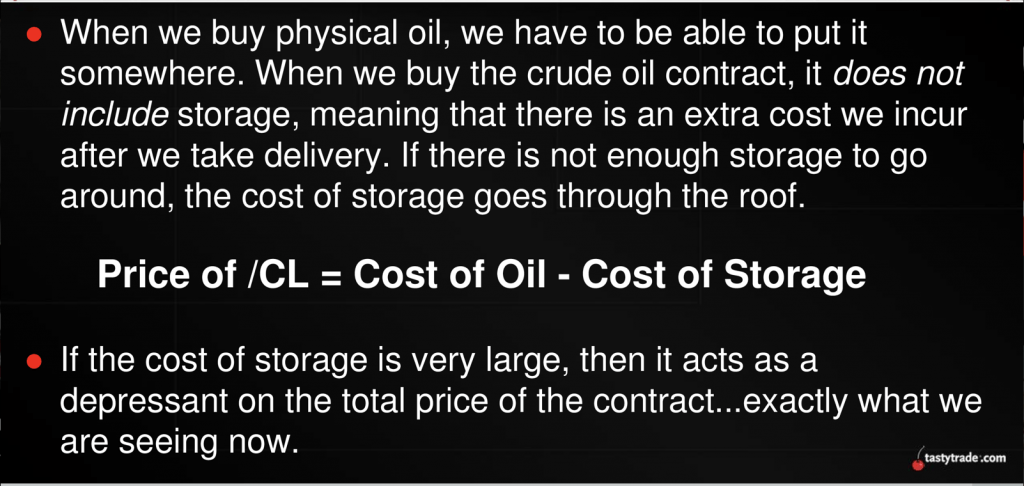

As highlighted on a recent episode of Tasty Extras on the tastytrade financial network, it turns out that the actual value of a given barrel of crude oil in a futures contract must also factor in the amount it costs to store the liquid, as outlined below:

As a result of all this, it’s likely that going forward, the price and availability of crude oil storage will be a much more important factor in pricing models, and the amount produced.

Questions over the potential disruption of a commodities market due to unforeseen circumstances may also ring familiar in the ears of precious metals traders, some of whom have long wondered about the overall security of gold, silver, and platinum markets when it comes to physical vs. “paper” obligations.

The thing is, one never fully understands a thing—whether it be a system, a process, a tool, or a market—until its capacities get stretched to the breaking point.

For example, nobody really wants to find out whether their sleeping bag actually functions correctly at temperatures that rate below the lowest recommended limit, but situations like this do arise.

In the oil market, market participants learned this past week that a sudden and dramatic oversupply in the market can push the price of a crude futures contract into negative territory.

And while the gold market won’t likely enter a phase anytime soon in which buyers are paying sellers to haul it away, the current situation involving drastically oversupplied energy markets begs the question of what might happen if/when there’s “too little” physical gold.

Basically, a scenario in which the physical gold market is drastically undersupplied.

As reported by a variety of media outlets in recent weeks, the physical gold market has seen a sharp increase in demand as the coronavirus epidemic has intensified. Stories range from a “five-fold” increase in demand, to common disclaimers that shipments will be delayed as compared to “normal” market conditions. Mints that make the bars and coins sought by investors and collectors have also reported dramatic increases in sales volumes, and some have even sold out completely of inventory.

The “paper” gold market has likewise seen a strong surge in demand as overall market volatility has increased. Paper gold refers to the non-physical gold market, where an investor holds a piece of paper that theoretically represents a claim for physical gold.

With paper gold, investors don’t own physical gold, but instead hold a promise to receive it.

Examples from the paper gold market include: gold certificates issued by banks and mints, pool accounts, precious metals futures, exchange-traded funds (ETF), and exchange-traded notes (ETN).

Circling back to the 2020 surge in demand, US-listed gold ETFs have added more than $7.7 billion in new investor funds so far this year. And in the last full trading week of March, GLD alone added $2.9 billion in new inflows, its biggest weekly haul since 2009.

Moreover, alongside the spike in demand, there’s also been a noticeable drop in ready supply.

The spreading of COVID-10 has disrupted the operations of gold mints and precious metals mines, and forced workers from these industries to shelter at home – much like everyone else.

In sum, that means that as the demand for gold has risen, the pool of available supply hasn’t followed suit.

That’s the exact opposite dynamic from the crude oil market, and likely represents the underlying reason why the two commodities have moved in opposite directions during 2020.

Gold prices are now at roughly 7-year highs, and have increased about 15% since the start of 2020. Oil prices, on the other hand, hit multi-decade lows recently, and then went negative.

A big question going forward is whether a similar pressuring of the gold trading system could produce a second unexpected event in the commodities trading world this year, or at some point in the future.

For some time, questions have swirled over whether the total amount of “paper” gold in the financial system has a sufficient amount of physical gold held in safekeeping to make good on all claims if every investor were to suddenly request physical delivery.

While many pundits in the marketplace might be skeptical of this somewhat outlandish scenario, those same voices would likely have never predicted that the oil futures market would drop below $0.

As a point of reference, it’s estimated that the totality of all the physical gold mined in the history of human civilization would fit snugly into the Centre Court stadium of Wimbledon.

It should be noted that previous dislocations in precious metals markets have occurred, although an extreme situation like negative crude oil has yet to materialize.

In 2008, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2019 the gold futures market spent time in backwardation, meaning that the spot price for gold moved above the short-dated futures contract value. In layman’s terms, that means the demand for gold available immediately (spot price) was greater than demand for gold that would be delivered in the future.

It may not be surprising to hear that gold markets briefly moved into backwardation again in March of 2020, at the height of the recent panic.

This situation is atypical in commodities futures markets because of the storage component in pricing—the same factor that received so much attention when oil prices got flattened recently.

Commodities markets are usually the opposite of backwardized, and instead trade “contango,” meaning that longer-dated (future) deliveries are more expensive due to associated storage costs that need to be paid in between.

What’s so unusual about backwardation in the gold market is that the physical market for precious metals is theoretically more finite when compared to consumable commodities. For example, when oil or corn is perceived to be in short supply due to drought, the market can backwardize as traders attempt to buy it immediately, due to fears it won’t be available later.

But these are consumable products, which need to be replenished. A precious metal like gold doesn’t decompose or degrade.

With the amount of gold in circulation a somewhat known quantity, there shouldn’t be any reason to pay a premium to receive it immediately. Paying more to receive physical gold right away, as compared to a future delivery, would also imply negative storage costs.

Backwardized gold only seems logical if one assumes that future delivery isn’t guaranteed. Unlike the oil market, which screamed recently there was nowhere to store it, a backwardized physical gold market implies there’s nowhere to find it.

Thankfully, some gold mines and gold mints have already started coming back online, suggesting that the supply side of the gold market may be normalizing. The fact that these entities were working at reduced capacity may have been enough to push gold markets into non-standard (i.e. backwardized) territory.

Realistically, a dramatic breakdown in the gold market (which might actually present as a super-spike) can’t be viewed as highly likely. But then again, an infectious disease epidemic wasn’t included in most 2020 pricing models either, nor was negative-priced crude.

While it may not seem likely, one can see how a dislocation in the gold market, one starving for physical gold, could result in a strong, unexpected rally—the exact opposite of what has occurred in a flooded crude oil market.

As such, investors and traders might want to tread lightly when entering positions that involve short upside exposure in gold (or any precious metal) during the remainder of the corona crisis, and possibly beyond.

This could mean utilizing defined-risk trading structures, as opposed to undefined-risk positions—the latter of which can open a portfolio up to outsized (and theoretically unlimited) losses.

What’s been clearly demonstrated in the 2020 trading year is that risks in the current market environment are more intense than previous years, even if potential rewards are too.

Investors and traders therefore need to ensure they’ve accounted for tail risk (i.e. large, unexpected moves) like negative crude, or super-spiking gold, when considering and deploying new positions.

To learn more about tail risk, readers are encouraged to review this previous episode of Market Measures on the tastytrade financial network when scheduling allows.