Die Probability

Tackling the dicey subject of calculating the probability of contagion, and the mortality of the coronavirus

Americans are struggling to understand the risk of catching and transmitting Covid-19. Should they feel 10 times as scared if confirmed cases increase tenfold in their city or state? Let’s figure it out.

Daily risk

Attempts at rationalizing risk often produce very large numbers that people find difficult to keep in perspective. They can run into the hundreds, thousands and millions. But alternative methods can illustrate the probability.

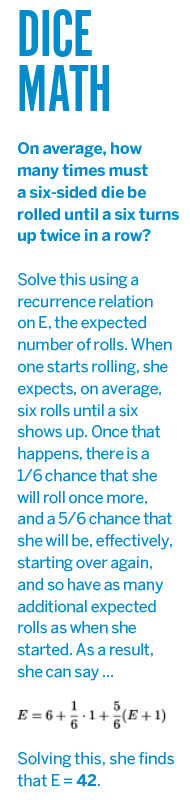

Imagine throwing a handful of dice. What are the chances that they all land on a six? Well, with two dice, the chance of that happening is just one in 36, (1/6 x 1/6) or 2.8%. Roll more dice at the same time, and the numbers rise quickly. With six dice, the chance of rolling all sixes rises to one in 46,656 (66) rolls.

For simplicity, let’s refer to levels of risk in terms of “two-dice risk” and “six-dice risk.” Notice that the probability of throwing sixes on six dice is much lower, and hence safer, than when throwing just two. The more dice, the safer it becomes.

Every day, people expose themselves to some degree of risk. That’s unavoidable. Most tasks—such as commuting to work—lie below the threshold of acceptable risk. They’re safe enough that people perform them without significant concern. (Although they ought to take sensible precautions, such as wearing a seat belt.) How risky are typical daily tasks? Let’s examine a few.

Flying. Taking a commercial flight exposes a passenger to a nine-dice risk. That’s an incredibly small probability, at around 10 million to one. Yet, many would-be travellers develop a fear of flying that demonstrates the difficulty of rationally assessing risk.

Driving. Traveling 100 kilometres by car exposes the occupants of the vehicle to only a tiny degree of risk. If they were to take that journey each weekday for a year, the cumulative risk works out to the equivalent of throwing six dice.

Canoeing. Canoeing typically exposes paddlers to a risk equivalent to throwing six dice each year, based on 141 deaths annually on 10 million canoe trips.

Drinking or smoking. A moderate drinker or smoker increases the chances of developing heart disease and cancer, typically putting life at risk with six dice over the course of a year. For heavy smokers and drinkers, the risk becomes stronger, so they are playing with fewer dice.

Personal risk of COVID-19

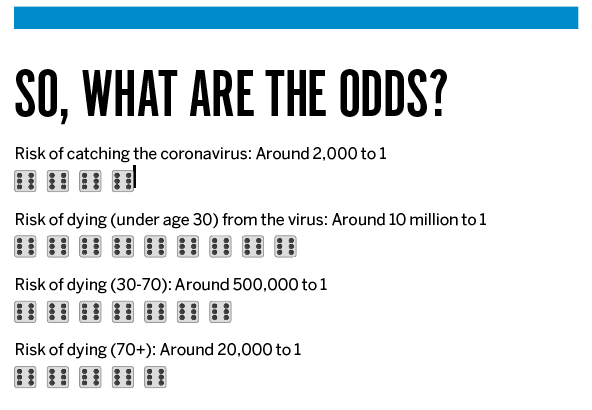

What’s the number of dice when it comes to the coronavirus? The sources of risk break down into two parts: (1) the risk of catching the virus, and (2) the risks once someone has the virus. The total risk can be found by adding the dice from each part. For example, if each of these parts is a three-dice risk, then the total risk is six dice.

Risk of catching the virus

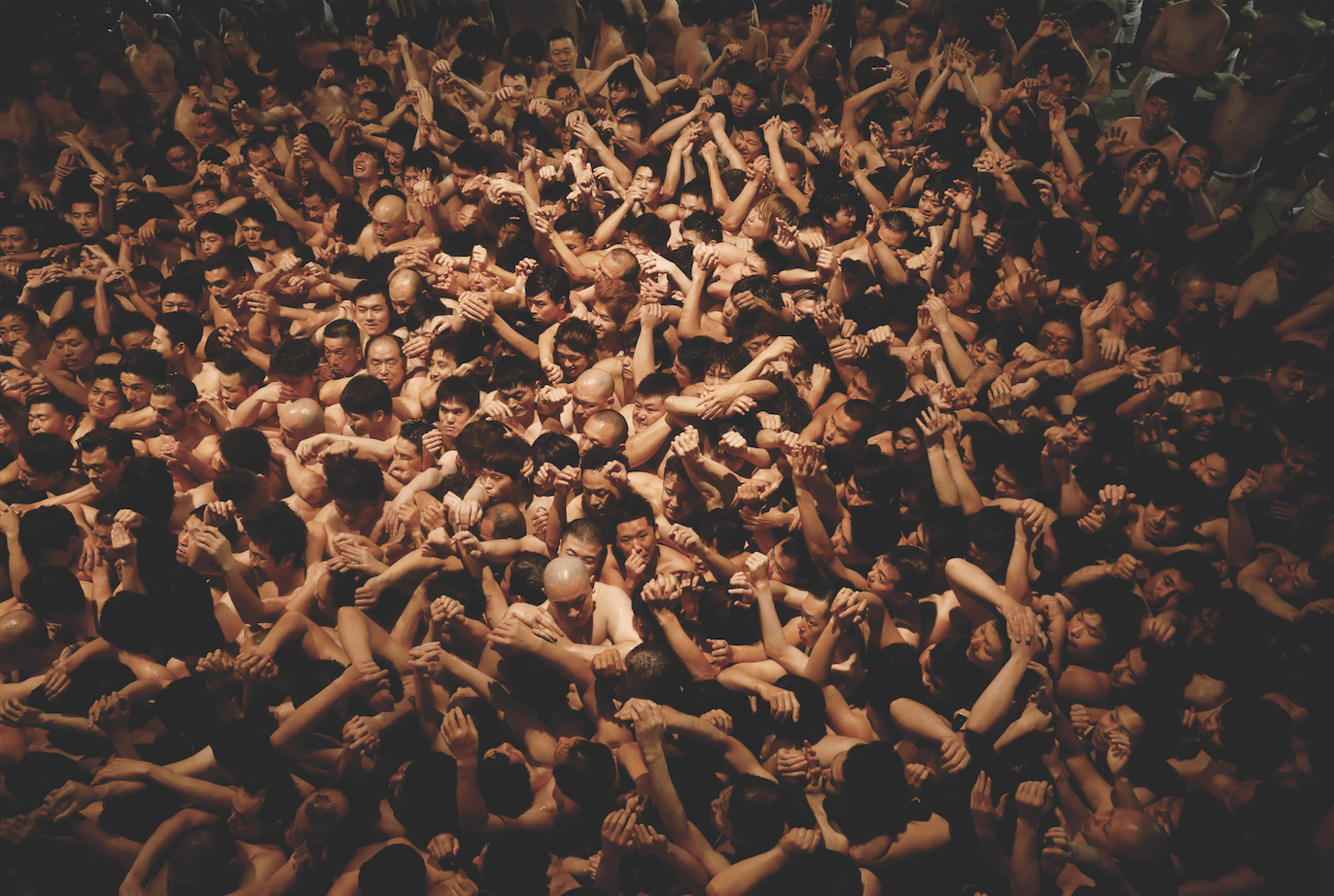

The risk of contracting the coronavirus depends partly upon behavior, such as masks and social distancing, and partly upon environment—how many sick people are in the vicinity. Environmental risk varies from region to region, from country to country and from one week to the next.

In the early stages, when the virus is just beginning to spread through a country, perhaps only one in 10 million people catch it each day. That means that someone going about daily life as usual would face a nine-dice risk each day of catching the virus. That’s an incredibly low risk.

However, if the virus spreads out of uncontrol, the pace of infection increases. At Week 1—defined by the infection rate of one in 10 million people catching it per day—people start with nine dice in hand. But in Week 2, the virus has spread to roughly six times as many people as the week before, and people would have eight dice.

In Week 3 they have seven, and by Week 4 they have only six. Remember, a six-dice risk is still low—not something people would tend to worry about. But if the virus continues to spread, people would face a four-dice risk in Week 6. That would mean one in 1,300 people would contract it each day. For a country the size of the United States, that would result in more than 250,000 new infections each day.

How many infections per day are happening right now? The real number is tricky to pin down, especially in countries without extensive testing. But the number of deaths per day could serve as a slightly more reliable indicator.

The challenge in using deaths as an indicator arises because of the significant lag between infection and death. The death rate provides a glimpse of the infection rate of two weeks ago, not today’s infection rate.

When will a country hit the daily four-dice level? That’s where cases are rising in an uncontrolled manner and there’s more than one death per million, daily. Italy reached that point March 8— the day before the country went into quarantine. (They recorded 1,492 new cases that day, but (a) a substantial delay occurred between infection and diagnosis, largely because of the incubation period of the virus, and (b) many less-severe cases are never tested).

The U.S. reached the four-dice level when it passed 327 deaths per day, back in March. As of July 14, it has yet to fall below this threshold and was having more than 700 deaths per day. Once a country enacts a lockdown, the infection rate begins to fall, and the associated risk falls with it. The dice increase in number.

Risk after infection

Some people who catch the virus don’t get sick. Others develop symptoms and recover within a few days. A small proportion die from complications. The risk of fatality for those under 18 is around one in 20,000. That’s a five-dice risk.

For those in their 30s it’s a four-dice risk, and for those in their 60s it’s a two-dice risk. The figures may improve with the arrival of better treatments, such as antivirals.

Many younger people are less concerned about their own well-

being than about passing the virus to someone more vulnerable because of existing health or immunity problems. So, in a sense, everyone’s risk after infection can be thought of as a two-dice risk. That’s roughly the chance that an infection will kill the person who catches it or someone to whom they pass it.

If the risk after infection is represented by two dice, and the risk of catching the virus is (say) five dice (depending upon the situation), what do the two risks mean in combination? Simply add them together.

The United States was at a four-dice risk of infection at press time. Combine those dice with the two-dice risk of death to find typical Americans are subject to a six-dice (1 in 46,656) risk of losing their lives to coronavirus.

Fergus Simpson, Ph.D., is a senior researcher at Prowler.io, where he applies Bayesian statistics to problems in machine learning. He earned his Ph.D. in astrophysics at the University of Cambridge.

@frgsimpson