GLP-1, the FDA and RFK-J Take on the Food Biz

Junk food manufacturers and restaurant owners are trying to adjust to three looming challenges

Restauranteurs and food manufacturers are facing a perfect storm of challenges to the way they do business.

First, new medications are causing users to shun junk food. Second, the FDA is contemplating a ban that would change the way a lot of foods look. Third, JFK Jr. is declaring war on American obesity and foodborne toxins.

GLP-1 drugs and junk food

The pharmaceutical in this trifecta of challenges, usually known as Ozempic, was developed to reduce blood sugar and thus combat diabetes. It turns out it helps reduce obesity, too, and that’s where things get complicated.

Just as an aside, the med’s development got a boost a few years ago when scientists came across something similar in the venom from the Gila monster, a lizard native to the Southwest. But we’ll put that tale aside for today.

Back onto the subject, the drug often called Ozempic is among several related to Glucagon-like peptide-1—or GLP1 for short. Besides Ozempic, brand names include Mounjaro, Wegovy and Zepbound.

Annual sales of those diabetes and obesity fighters are expected to reach $100 billion by 2035. Several companies have been involved in the research, production and marketing, but Novo Nordisk (NVO) and Eli Lilly (LLY) have emerged as the biggest players.

About 7 million American are already taking one of those meds, and the number could reach 24 million by that oft-cited year of 2035. But with 100 million citizens considered obese, the market could continue to grow indefinitely.

The drugs make users feel full, and they find themselves giving up sugary treats and replacing them with unprocessed fruits and vegetables. People taking the drugs seem to be rewired to reject chemical-laden ultraprocessed foods modified with artificial colors, bleaches, and added sugar, salt and preservatives.

People who’ve kicked their addiction to such foods love their newfound diets and find their old ways of eating repugnant, according to testimonials published in The New York Times.

The newspaper reported that a focus group participant put it this way: “Celery tastes like celery, and carrot tastes like carrot. Strawberry tastes like strawberry. I just started to realize that they taste wonderful by themselves.”

Another participant described negative reactions to formerly cherished foods. “A HoHo no longer seems like food,” one woman told the focus group. “It tastes plasticky or feels plasticky in my mouth.”

That’s good news for people grateful for losing excess weight, and some have shed more than a hundred pounds with the help of GLP1drugs. But it’s a less-exciting new trend for fast-food restaurants, food manufacturers and grocery retailers.

The food industry reacts

Science has helped makers of ultraprocessed foods develop products designed to trigger pleasure in the brain and ward off feelings of having had enough to eat. Some of the chemicals they’ve used taste bad, so they’ve added other chemicals to mask the unpleasant flavors.

Not much is known yet about how GLP1 influences users to choose natural foods, so the makers of artificial foods are hard at work to preserve their influence on what America eats. One success for industrial foods has been Fairlife, a line of sweet protein shakes owned by Coca-Cola (KO) that The Times says has been lauded on GLP1 forums.

But in general, the food industry is continuing to lose business as GLP1 proliferates. The drug is taking at least part of the blame for declining sales over the last six quarters at companies that include Kraft Heinz (KHC) and Campbell’s (CPB).

Fast food restaurants are feeling the pain, too, according to a report in Franchise Times. GLP-1 users report patronizing fast food restaurants less frequently, with their visits to burger joints down 45%. Their meals in all types of restaurants have declined 28%.

Even when the GLP1 crowd does show up at eateries, they’re spending less because they skip the sides, deserts and alcohol, the website says.

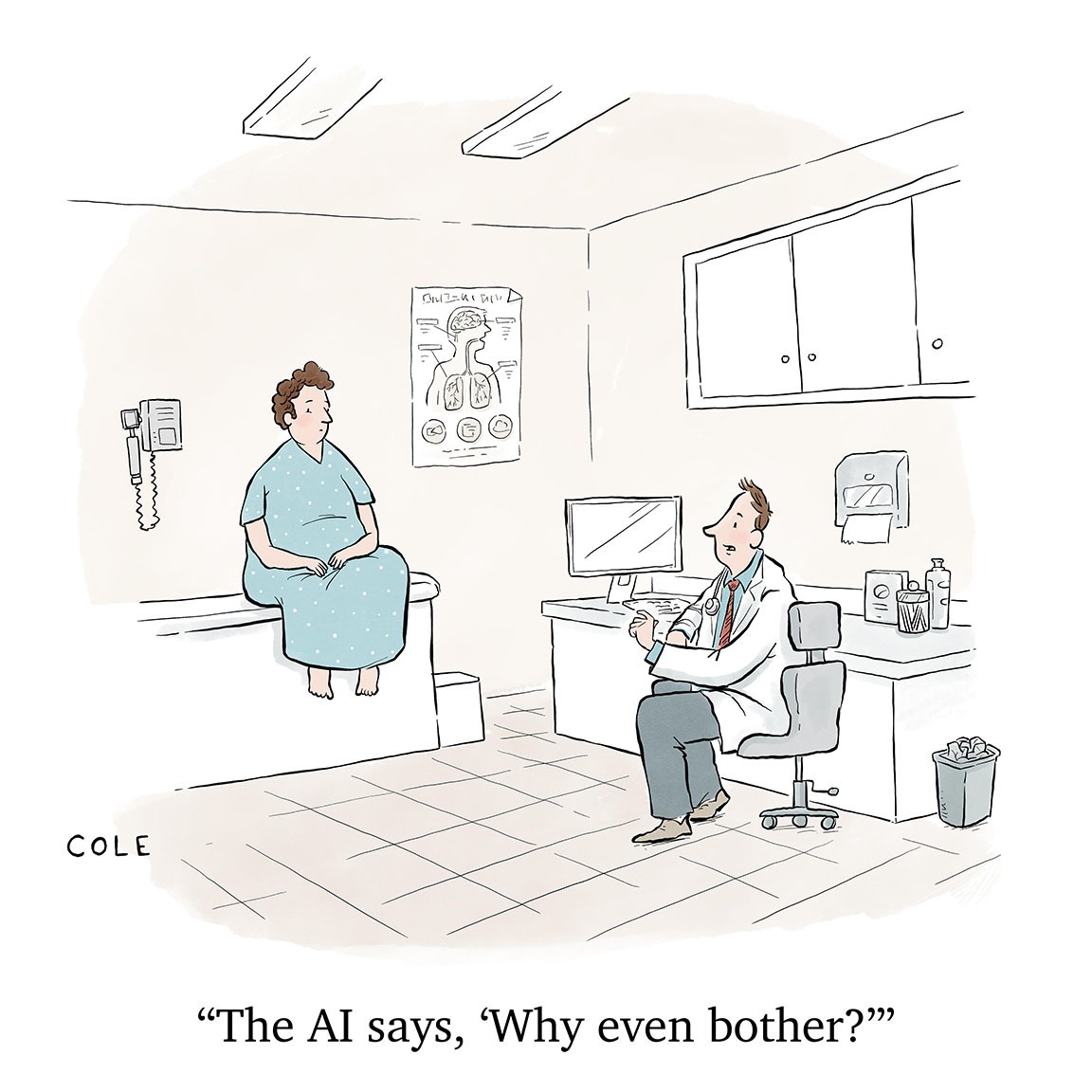

Restauranteurs are responding by changing their pricing and revamping menus with the help of artificial intelligence. One example is the introduction of smoothies that are nutrient-dense, high in protein and rich in fiber.

But the problems for the restaurant industry and for food manufacturers don’t end with taste and nutrition. Change is also in the air for the way food looks, and that can have grave consequences for theirs businesses, too.

Take the case of Red No. 3, a cherry-colored food additive made from petroleum.

Big Red

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is considering a ban on the red food dye in response to a lengthy list of petitioners ranging from the Center for Science in the Public Interest to an organization called Real Food for Kids. The process has been underway for a while, and the period for comment ended last year.

Red No. 3 is incorporated into all sorts of foods, beginning with the obvious—like crimson jellybeans or pinkish sausages—but it also shows up where some might not expect it, like vegetarian meat substitutes. It was approved for use in food in 1907, when the research into its effects was scant.

But then science learned more about it—enough that the Feds banned it in cosmetics 30 years ago because high concentrations can cause cancer. Still, it’s remained in food until now despite more recent evidence that small amounts may or may not trigger hyperactivity and inattention in children, the primary market for brightly colored red foods.

Whether or not the FDA moves forward with a Red No. 3 ban, the food industry is making moves to eliminate it from the national diet. In one example, Kraft Heinz has replaced it in mac and cheese with color from spices like paprika and turmeric.

A ban could come any day, according to reports bouncing around all over the media. But prohibiting use of the dye in food would be just a small part of the change sought by Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who’s President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

RFK Jr. says he and President-elect Donald Trump are forming a partnership called “Make America Healthy Again,” or “MAHA,” with the aim of doing no less than transforming “our nation’s food, fitness, air, water, soil and medicine.”

MAHA to augment MAGA?

RFK Jr. has big plans if he wins the Senate confirmation and take the reins at the department. He explains some of his a mbitions in a YouTube video that begins by highlighting green MAHA hats with white embroidery—a more relaxed-looking version of the ubiquitous red MAGA caps.

“And the first thing you need to do is get one of these hats, and we need everybody walking around and wearing it everywhere they go,” RFK Jr. says in the video. But he emphasizes that the cap alone “is not going to be nearly enough.”

He wants to appoint public servants to replace the current administrators of federal health agencies that he maintains have become the “sock puppets” of the industries they’re supposed to regulate.

The new regulators would eliminate toxic chemicals in food and conduct research and find the causes of chronic diseases. They’d also support alternative medicine alongside Western medicine, he says.

RFK Jr. ends his video presentation with a call to donate to MAHA or support it by buying merchandise on its website. Apparently, altering the American approach to food and scrapping the culture surrounding it won’t come cheap.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox editor-in-chief.