A Sound Investment

The public can profit from music royalties through bonds, ETFs and online platforms

When David Pullman hears Fame by Davie Bowie, he flashes back to the moment in 1975 when the song blew him away for the first time.

“I was walking down the street and I felt electricity from the song—like shivers,” Pullman says.

Little did Pullman know he’d be approached 22 years later to help monetize Bowie’s extensive music catalog. The performer had decided not to sell the rights to his songs, so Pullman, an investment banker and founder of The Pullman Group LLC, came up with the idea of Bowie Bonds.

They were the first-ever asset-backed securities in the world of music and entertainment, and revenue from Bowie’s albums served as collateral. Investors snapped up $55 million worth of the bonds, and royalties generated by Bowie’s music repaid that amount over a 10-year period.

After the quick adoption of Bowie Bonds, Pullman created a successful series of Pullman Bonds for other legendary songwriters and recording artists, including James Brown, The Isley Brothers, Ashford & Simpson and the Motown team of Holland-Dozier-Holland.

The bonds enabled artists to convert intellectual property into a tradeable asset, while investors profited from the steady stream of royalty payments.

“These deals are like Redwoods because they don’t make them anymore,” Pullman says in an interview with Luckbox.

In an ever-evolving industry, Pullman Bonds aren’t viable anymore, Pullman says. Instead, the industry has seen staggeringly large private equity deals—think of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen collecting more than $500 million each for their catalogs. But some very small equity deals have flourished, too.

Before streaming services like Napster transformed the music industry, major record companies tended to have 500 artists on their labels, but now the number is dwindling, Pullman notes.

“Then they had 100, then they had 50—now they have 25,” he notes. “So, you’re not going to see artists put out 10, 20, 30, 50 albums like they used to. Now, sometimes labels put out one or two albums, and then they move on to the next artists because they renegotiate after the first two and they just aren’t as productive.”

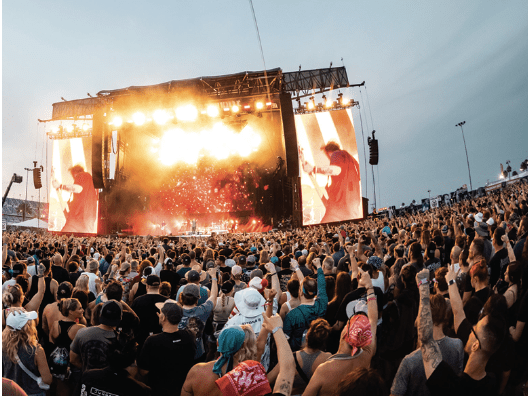

That’s not to say artists and songwriters aren’t creating catalogs. The numbers from streaming, concert revenue, merchandising, record sales, digital downloads and advertising can become astronomical, Pullman says. Taylor Swift, for example, released her 11th original studio album in April and has four re-recorded studio albums, five extended plays and four live albums.

The music industry just keeps expanding. Revenue is growing 12% annually and will reach $53.2 billion by 2030, according to Goldman Sachs. Today, something like 600 million listeners pay for subscriptions to streaming services, but that figure will eventually double to 1.2 billion, predicts Lisa Yang, Goldman’s managing director of media and internet.

So, investment vehicles should not be scarce.

Music fund

Making money in the music industry is no longer limited to big institutions with tons of capital and insider connections—it’s for everyone.

In July 2023, David Schulhof introduced the first-ever global music industry exchange-traded fund (ETF)—Musq Global Music Industry ETF (MUSQ). Schulhof, founder and CEO, was originally looking to kickstart another publishing company two years ago but realized there was no edge.

“I looked around and saw there were so many private equity-backed companies, hedge funds, pension funds, and they were all like sharks in the water—fishing after the same [deals], like Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty,” Schulhof says. “I was like, ‘I can’t do this. It’s not a strategy.”

So he designed the ETF that he wanted to invest in and included 48 stocks in the modern music business.

The ETF is designed to create exposure to global, publicly traded companies and royalty funds in five categories: streaming, content distribution, live music ticketing, satellite radio and equipment technology.

“Around this time, ETFs were becoming popular, and I started analyzing the market,” Schulhof says. “I realized there was a huge demand for retail, yet there was no liquid product. There was no liquid and convenient way to invest in the music industry.”

Fifteen years ago, investors had to show $1 million to $5 million in assets to become an investor in the music industry, he says, and there was no convenient way for retail investors to democratize the situation.

MUSQ allows for diversification across many segments of the industry. “It’s the first pure play music ETF in the business today, which gives investors total diversification and access to the whole music industry, every aspect of it,” Schulhof says.

Plus, it offers a lot more tax advantages than mutual funds, he maintains.

MUSQ ETF Top 5 Holdings as of 6/25/24

APPLE ORD – 6.60%

ALPHABET CL A ORD – 6.09%

AMAZON COM ORD – 5.56%

SONY GROUP CORP – 4.22%

SPOTIFY TECHNOLOGY S.A. – 4.03%

Sonic exchange

Platforms like Royalty Exchange and SongVest offer the opportunity to invest directly in music catalogs and song royalties. While SongVest enables investors to purchase fractional shares of music royalties, Royalty Exchange allows investors to buy into assets directly.

“It’s really the only place with meaningful scale, where you can buy the actual royalties, rather than a company or fund that owns the royalties,” says Royalty Exchange CEO Gary Young.

Royalty Exchange serves as a marketplace for creators, songwriters, artists, or rightsholders to unlock the value of their music catalogs. It’s completely in the rightsholders’ hands to upload their song, or songs, onto the platform.

The rightsholders can set their desired price, as well as how long they want to allow investors to collect royalties. Investors are also able to review how much in royalties the rightsholder has made in the last few years and can make an offer to buy the royalty rights, or to collect all or some of those royalties going forward.

For example, someone who owns the international rights to some My Chemical Romance songs have the band’s entire international publishing royalties listed on the platform for $395,000 for a life-of-rights term. Investors have the option to buy at that price or make a separate offer. It’s up to the rightsholders to decide how they want to proceed.

The investment is in the rightsholders’ royalty revenue only. They are not buying the rights to the music.

“It’s basically time travel,” Young says. “You can go into the future and pull forward today the money you would have gotten over time. For thousands of songwriters who we’ve worked with, the right amount of money at critical moments in your career can make your career get bigger way faster than you could imagine.”

But what makes this a good addition to an investor’s portfolio? Young provides three reasons:

- Royalties provide a steady stream of income for a prolonged period.

- Music royalties aren’t correlated with the broader market, so whatever happens with the Federal Reserve or the bond and stock markets, won’t affect the royalties. They’re based solely on the consumption of music.

- The music industry is growing, and assets that generate a real yield are an attractive investment.

And while Bowie Bonds were riding on the success of a renowned artist, Royalty Exchange is a platform for any kind of songwriter or creator.

“We’re fundamentally a technology company, so we built the technology that lets us serve nearly everyone,” Young says. “Our mission is to create a liquid marketplace for these assets because we think that makes everyone richer.”

Royalty Exchange’s biggest deal to date was $18 million, and the smallest was $2,500.

The platform is seeking big catalog deals but also focusing on up-and-coming artists and songwriters.

“Do your due diligence and make sure that if you make a deal, you have a clear purpose for how you can grow your career or enrich your life with the money you get,” Young says.

Royalty Exchange

10%+ average ROI

2,000+ deals completed

$170 million+ transaction volume

Over 30,000 registered investors

13.3% average yield

Another platform for investing in music, JKBX, was launched in March. It works with music rightsholders to secure percentages of song royalties. The royalty shares are submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission for qualification as an asset. Once approved, investors can purchase a percentage of songwriter and recording artist royalties. For example, OneRepublic’s song Counting Stars, written by Ryan Tedder, is going for $31.37 per share.

“It’s like Bowie Bonds that are public,” Schulhof says. But instead of investing in an artist’s whole catalog, you can select specific songs.

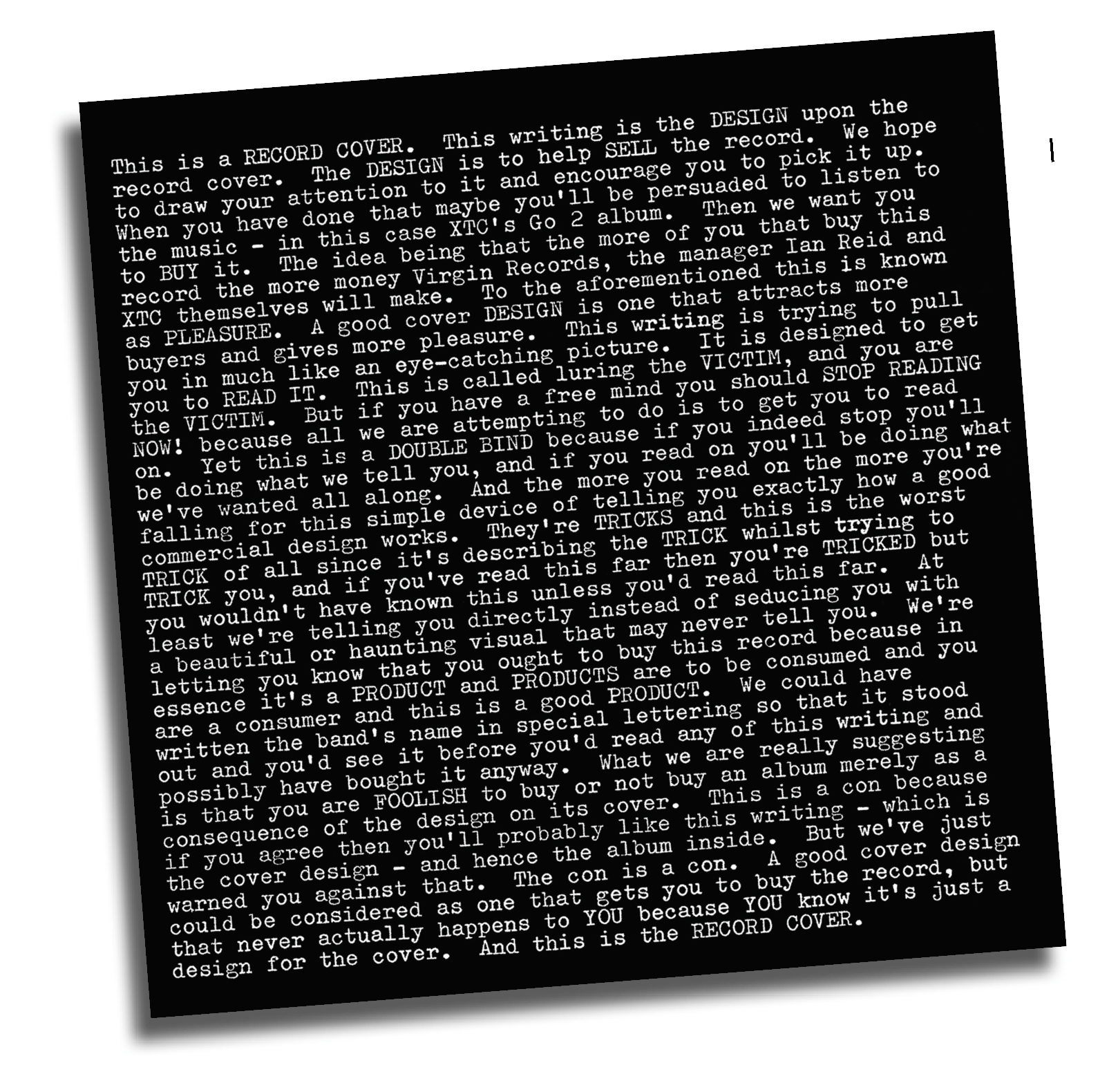

“Those are really exciting ways for artists to monetize their catalogs by themselves,” he continues. “What I’m seeing is the democratization of music. Songwriters, producers and artists being able to sell their works to the public now. It makes it accessible for the first time and have it be very liquid.”

Streamlined royalties

There’s a slew of ways to collect revenues from music today. Think of performance revenue from streaming and radio. Performing rights organizations—ASCAP, BMI and SESAC—collect royalties from radio broadcasters, and sit on the revenue for months. They pay it out quarterly. There’s always a lag in revenue reaching artists.

Under the Music Modernization Act of 2018, the nonprofit Mechanical Licensing Collective was established to issue blanket mechanical licenses for qualified streaming services in the U.S., such as Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon and Tidal. But, Schulhof says more could be done to streamline the process.

“Money market rates are 5%, with Treasury yields going up,” Schulhof says. “So, what they’re doing is they’re holding onto your money so they can make more money with it. That is not correct and needs to be fixed, and that’s what blockchain is doing.”

He says blockchain can track the performance of music and it has a direct payment rail—meaning one pay for one play. “In the perfect universe, it should be paid immediately,” he says.

On a similar note, Young says he’s excited about the “unstoppable digitalization of our lives.”

“Every new popular internet or smartphone platform is going to need a soundtrack,” he says. “Rights are becoming more valuable by the day because of things like TikTok and YouTube growing, and the massive expansion of streaming TV—all those folks need music for what they’re doing.”

A growth story

The Recording Industry Association of America’s 2023 year-end report revealed that recorded music revenues in the U.S. continued robust growth for the eighth consecutive year. Total revenue grew by 8% to a record high of $17.1 billion at estimated retail value. And streaming accounted for most recorded music revenue last year.

“In the U.S., streaming is growing 11% to 13%,” Schulhof says. “It’s growing up to 25% in emerging markets. Content is growing 9% to 11%. These are all like four, five, six times the GDP (gross national product), which is the investment case for music. It’s a real growth story.”

Country music, in particular, offers worthwhile investment opportunities Schulhof notes. It’s the longest performing genre because songs have a longer shelf life than pop hits and don’t spike up and down.

But Young says the music industry still underestimates the massive influence of streaming. It has turned intellectual property into an ongoing stream of payments.

Around 60% or 70% of all songs streamed on Spotify are two years old or older. So, when songs are released today, they have a significantly longer earning lifecycle than in the past.

“That tremendously increases the value of that music,” Young says. “I think a lot of songwriters, artists and producers over the last few years are coming to realize their rights are extremely valuable.”

Kendall Polidori is The Rockhound, Luckbox’s resident rock critic. Follow her reviews on Instagram and X @rockhoundlb, TikTok @rockhoundkp