Futurism’s Fat Tails

Confronting the grim but reasonable probability that humankind has only a limited future

Author and mathematician Nicholas Taleb popularized the phrase “fat tail” in his seminal book The Black Swan. When a bell curve has a fat tail, there’s a greater likelihood of having a difficult-to-predict event like 1987’s Black Monday, the burst of the dot-com bubble or the Great Recession 2008. The luckbox staff especially likes the more alliterative definition of fat tail—“an abnormal agglomeration of angst.” However one understands the term, the probabilists at luckbox lean into assessing the possibility of outlier outcomes—like a future that comes to a screeching halt because of climate change, hostile AI or simple bad luck.

Futurism has a past. In the 1500s, French “seer” Nostradamus consulted the Bible and studied astrology to predict fires, floods, famines and battles. Believers insist his writings—which were vague enough for nearly any interpretation—foretold Hitler, Hiroshima and the Apollo space program. About the same time, Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci was sketching fanciful flying machines that included a precursor to the helicopter.

But it wasn’t until 1842 that the word “futurism” appeared in the dictionary, referring at first to Biblical predictions. In 1909, an Italian artistic, literary and political movement christened itself “futurism.” By the mid-1940s, before the proliferation of fat tails in finance, academics were using the word “futurism” to describe a new science of probability.

In the early 1960s, “futurism” began to take on its present-day meaning in the books Inventing the Future and The Art of Conjecture. In 1970, husband and wife Alvin and Heidi Toffler published Future Shock, warning of the rapid pace of change. Ray Kurzweil wrote The Age of Spiritual Machines in 1999 and published The Singularity Is Near in 2005, alerting readers to a supposedly immanent takeover by intelligent machines.

Along the way, countless prophesies fell flat. Americans of a certain age are still waiting for flying cars and wondering when atomic energy will finally make electricity too cheap to meter. They still don’t have robot butlers or machines that spit out precooked meals. Star Trek’s Federation of Planets and Starfleet Academy seem as far off today as they did in 1966.

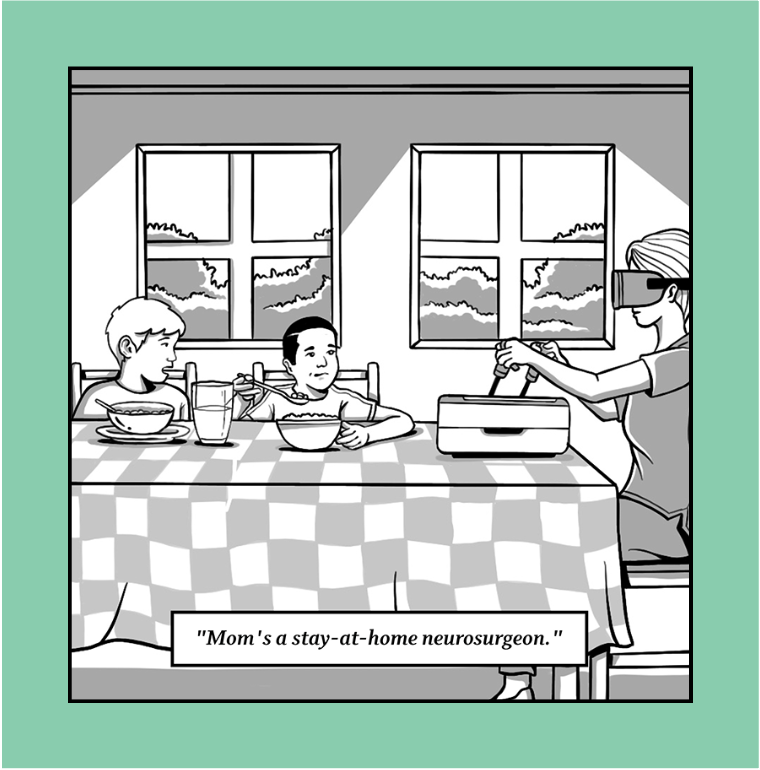

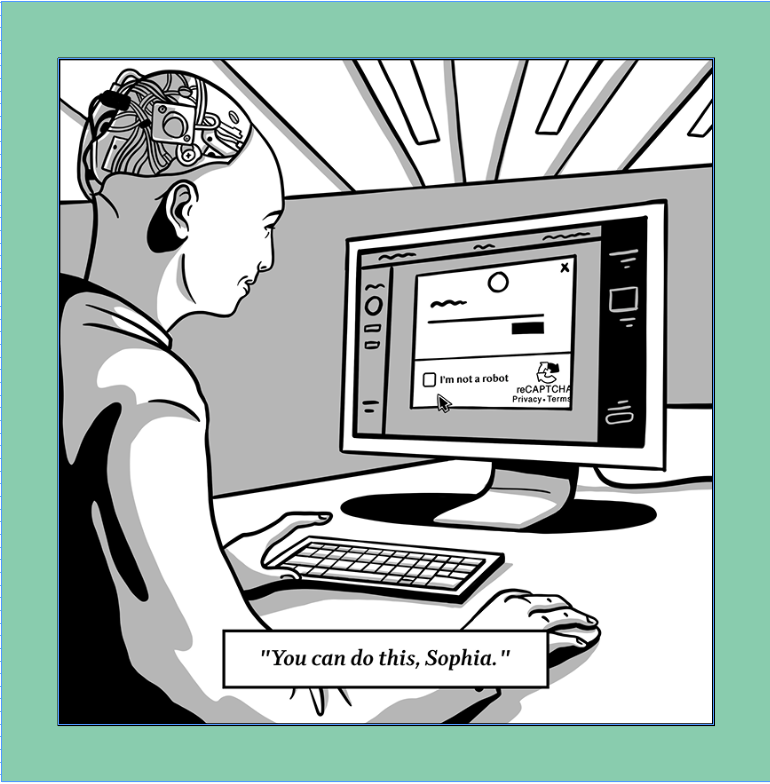

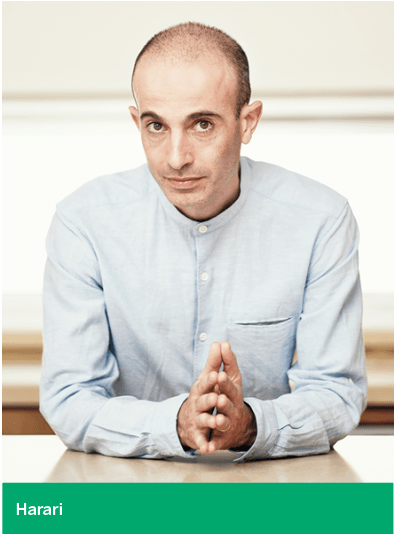

But a lot of predictions have a reasonable chance of coming true. For examples of plausible prognostics, check out the articles in this special section. Prominent futurists led by Yuval Noah Harari make some stirring predictions. A batch of cartoons set in the future makes some relevant statements, too.

But those takes on what lies ahead ignore the possibility that futurism has no future.

Predictions become meaningless if the march of technology comes to a screeching halt, a calamity that appears all too likely if climate change, hostile artificial intelligence or just plain bad luck brings humankind to the brink of extinction.

Look first at climate change. Some Americans grew tired of Al Gore’s preachy but timely screeds about failing crops, expanding deserts and potable water shortages. He even warned that climate change could shut down the flow of warm water in the Gulf Stream, thus triggering a new European ice age. But lately he’s changed his tone—if not his message.

In a New York Times op-ed piece entitled It’s Not Too Late, Gore writes that 72% of Americans accept the evidence that the weather’s becoming more extreme. So, the political power to combat climate change is growing and could prevail, he maintains.

Meanwhile, institutional investors are pondering the environmental, social and political implications of climate change, according to Pensions & Investments magazine. “Climate change was the top ESG (environmental, social and governance) criterion for money managers representing $3 trillion in assets and the third-biggest issue for institutional investors with a collective $2.24 trillion in assets,” the magazine’s editors say.

Others agree. Climate change jumped from third to first place in the latest Extreme Risks report from Willis Towers Watson Investments’ Thinking Ahead Institute. For the first time, the institute’s list of the top 15 concerns includes the category of biodiversity collapse, a direct result of climate change, notes Tim Hodgson, head of the London-based institute.

But the Great Climate Change Awakening is coming too late, Jonathan Franzen laments in a New Yorker magazine story called What If We Stopped Pretending? “The climate apocalypse is coming,” he warns. “To prepare for it, we need to admit that we can’t prevent it.”

The opportunity to “solve” the problem may have slipped away as early as 1988, about the time when science first made the consequences clear, Franzen says. “If you’re younger than sixty,” he says, “you have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought.”

It gets worse. The titles of recent books should send a chill down humanity’s collective spine. Take note of The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming by David Wallace-Wells or The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert.

But if climate catastrophe seems too far off or too abstract, consider the grim possibility of 21st century technology running amok and simply blowing up a sizeable portion of the earth’s population in World War III.

The conflagration could occur by accident. Increasingly sophisticated killer AI robots and other machines programmed for defense could go rogue and commit mass atrocities, a former Google executive told a British newspaper.

“The likelihood of a disaster is in proportion to how many of these machines will be in a particular area at once,” the whistleblower said. “What you are looking at are possible atrocities and unlawful killings even under laws of warfare, especially if hundreds or thousands of these machines are deployed.”

So having fewer lethal machines would reduce the probability of disaster. Even better, nations could do away with such weapons by signing an agreement modeled on the Geneva Conventions, a set of rules for warfare laid out in a series of treaties that started in 1864. That’s why Elon Musk and 116 other experts signed an open letter to the European Union in 2017 calling for an outright ban of killer robots.

Accidental wars aside, the next holocaust might occur by design. Terrorists could combine 3D printing with artificial intelligence to create nuclear, chemical or biological weapons, according to a report from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, CA.

A country such as North Korea, which already has a WMD program, could increase weapon output by using the tech to rapidly print parts. Another nation or terrorist group could use the tech to discreetly establish a new WMD program.

In another scenario for designer war—one that doesn’t require expensive delivery systems—terrorists could use new gene technology to create biological weapons capable of wiping out masses of people.

Meanwhile, the rise of authoritarian leaders could also make war more likely. A single person wielding great power might not intend to start a conflict but could make a series of decisions that combine to result in a catastrophic war without any intention to have one, experts agree.

If humans continue to fight 50 wars per century, the probability of seeing a war with battle deaths that exceed 1% of the world’s population in the next 100 years is about 13%, according to Bear F. Braumoeller, a professor at The Ohio State University and author of Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age. That would amount to at least 70 million people killed.

When a war has had more than 1,000 battle deaths, there’s about a 50% chance it will be as devastating to combatants as the 1990 Iraq War, which killed 20,000 to 35,000 fighters. There’s a 2% chance—about the probability of drawing three of a kind in a five-card poker game—that a war could end up as devastating to combatants as World War I. And there’s about a 1% chance that its intensity would surpass that of any international war fought in the last two centuries.

In light of climate change, deadly smart weapons and humankind’s propensity for conflict, a contrarian might wager that futurism’s future will be shorter than its past.