Taxing the Trade

An advocate and an opponent each have their say about a proposed financial transaction tax

Candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination support a financial transaction tax (FTT). The levy on transactions of publicly traded securities would offer a progressive means of raising tax revenue and increasing market efficiency, proponents say.

Advocacy groups representing individual and institutional investors, including high-frequency traders, have pushed back. They argue that high-frequency trading has lowered the cost of transactions and that an FTT would affect Americans across the income spectrum.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy has waded into the debate with a report on the possible ramifications of an FTT. Luckbox invited Steve Wamhoff, the group’s director of federal tax policy, to make the case for the FTT, and called upon Tom Sosnoff, co-CEO of financial media firm tastytrade to offer a rebuttal.

Are financial transaction taxes a new idea?

Steve Wamhoff: The concept is not new at all. In fact, the United States had a small tax on trades from 1914 to 1966, and that began at a rate of just 0.02%. It did not cover as many transactions as the FTTs proposed today. The U.K. has been taxing stock trades going back to around 1700, so the idea has definitely been around. It’s not a new idea.

Tom Sosnoff: The idea that something is OK because it was done in the past is ridiculous. Thank God we didn’t copy the U.K. model of market structure and free market enterprise.

What are the benefits of an FTT?

SW: An FTT could reduce inequality in a couple of different ways. Some of the tax is not passed on from the financial institutions to investors because some trades would no longer occur as a result of a tax. Some of those trades were not in the interest of investors to begin with. So there’s some evidence that some of the financial transactions made today merely churn assets. It just generates fees for financial institutions without really benefiting the investors. And there’s a lot of evidence to support that.

In one possible scenario, financial institutions would directly pay the tax. But in another possible scenario, they would pass it on to investors. So, investors would pay higher transaction costs on these trades, or they would just not do some of these trades that would otherwise benefit them.

Because most investment is done by well-off households, this would make the FTT a progressive tax and that would reduce inequality. So, for example, the latest data I was looking at from 2016 showed that in that year, the wealthiest 10% of households in the United States owned 84% of the stocks, while the bottom 60% of households owned just 1.8% of stocks.

If this tax is passed on to the investors, it will be paid by well-off households making it a progressive tax. And that will reduce inequality because it will increase taxes on the wealthy and have little effect on anybody else.

TS: The argument that adding a financial “sin” tax to individual investors to reduce income inequality is a bit of a stretch. I’m fine with taxing institutional investors all you want. However, self-directed investing is not about the wealthy. The average account size across the entire industry for active investors is $25,000. The average do-it-yourself investor is learning how to take risk and make decisions—all while becoming strategically articulate and financially savvy. Why should the small, self-directed investor bear any of this unfair toll?

Could an FTT make markets more efficient?

SW: Some of the trading that might come to an end as a result of an FTT is not benefiting investors to begin with. It is just generating fees for financial institutions and not benefiting investors—the economy would be more efficient without it. The economy is actually better off without that. But even beyond that, there seems to be trading that even when it’s profitable to certain investors does not benefit the broader economy or society.

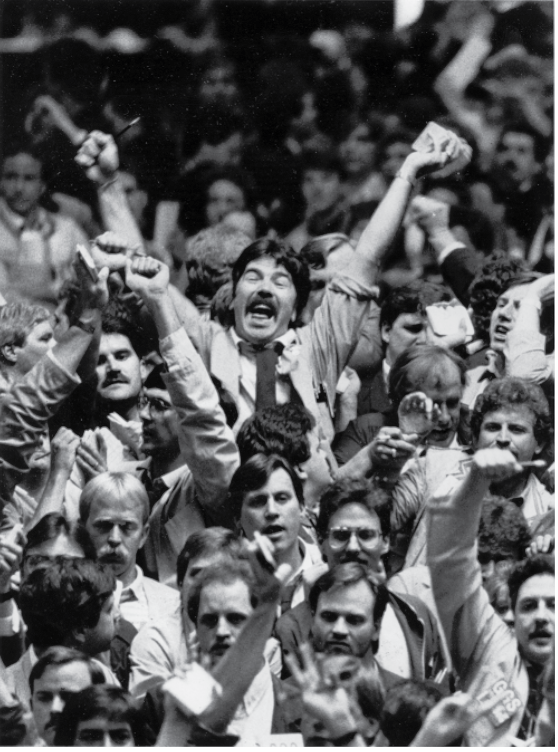

For example, when we think about flash (high-frequency) trading, that appears to reward people who manipulate the marketplace rather than people who are simply identifying sound investment opportunities. Flash trading uses technology to view another party’s order seconds before that information is available to everybody else, and then they try to profit from this asymmetrical information.

Flash trading rewards manipulating the marketplace rather than identifying sound investments. In fact, flash trading is what some economists have identified as making our system less efficient. This flash trading relies on an extremely large volume of trades, and that is the type of activity that an FTT would dramatically reduce.

TS: High-frequency trading and high-volume market-making have added liquidity, tightened markets, reduced trading costs and delivered investors more efficient price discovery. The entire globe trades in the U.S. markets simply because we have the most efficient and deepest pool of liquidity in the world. The reason our exchanges have been able to maintain market leadership is mostly because we have the lowest fee structure and best technology. You never want to risk losing the role of being the global leader for capital markets.

What rate would you envision for an FTT?

SW: Proposals that are floating around now from Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.), called the Wall Street Act, imposes a tax of 0.1%—that’s 10 basis points—on financial transactions. There’s another proposal from Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) and Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) that assesses a 0.5% tax on stocks, a 0.1% tax on bonds and a 0.005% tax on derivatives.

TS: If you don’t understand the problem with an FTT then it’s impossible to make up a number. A fraction of one basis point is insane. The reason America is the leader of the free world and houses most of the richest companies on the globe is because we have the deepest pool of liquidity. Remember, liquidity rules. Politicians can mess with lots of stuff but they shouldn’t mess with the foundation of the liquidity pool.

How much revenue could an FTT raise?

SW: Over a decade we can raise hundreds of billions of dollars. The Congressional Budget Office examined a proposal that is very similar to, or maybe the same as, the Wall Street Tax Act—the proposal from Sen. Brian Schatz and Rep. Peter DeFazio. They estimate over 10 years the tax would raise more than $770 billion. So that’s an example of the magnitude we’re talking about.

TS: A far more sensible way of raising hundreds of billions of dollars without hurting individual investors is to order two fewer stealth bombers, stop building a border wall and collect a fair tax from the world’s wealthiest corporations, such as Amazon (AMZN), Google (GOOG), Apple (AAPL) and Faceook (FB).

The Democratic presidential candidates favor an FTT. Sen. Bernie Sanders has offered a specific FTT plan, and former Vice Pres. Joe Biden has indicated support for the tax. Your reaction?

TS: As a Democrat, this makes me sad. The way to reverse inequality in America is not through a misunderstood tax that has no long-term sustainable benefits. The key to reversing inequality is to continue to make America the primary center for productive market structure, business and entrepreneurship. You can do that without messing with the financial system. It’s the driver of growth. Just fix a broken tax code.

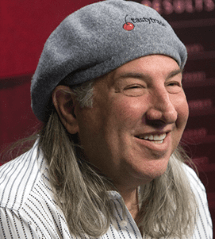

Steve Wamhoff serves as director of federal tax policy for the left-leaning Washington-based Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (itep.org). He previously worked as Sen. Bernie Sanders’ senior tax policy analyst and has held positions with the Social Security Administration’s Office of Policy and the Coalition on Human Needs. @stevewamhoff

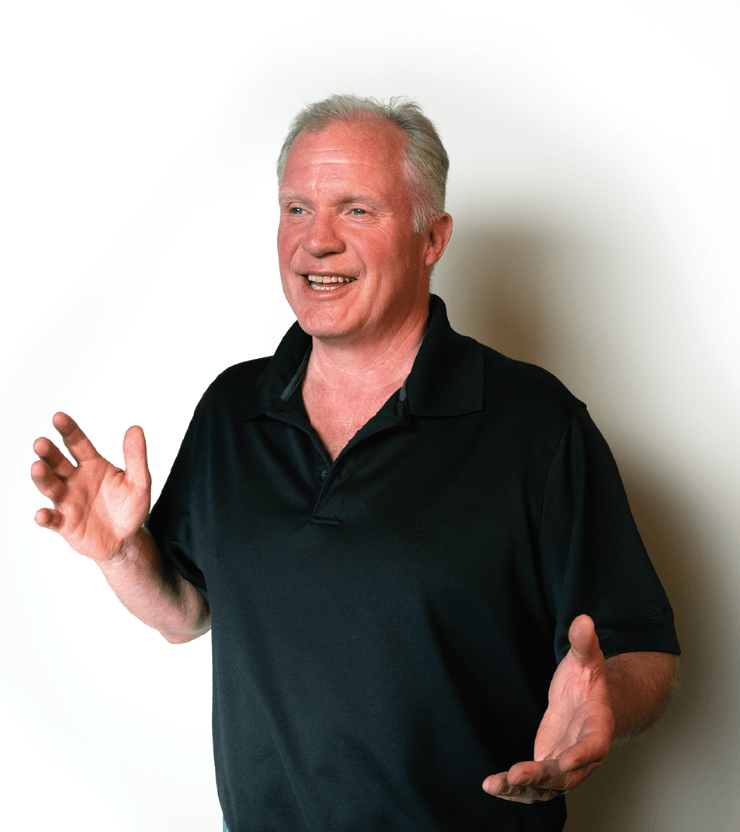

Tom Sosnoff, an online brokerage innovator and financial educator, founded thinkorswim in 1999, started the financial media firm tastytrade (which owns this publication) in 2011 and launched brokerage firm tastyworks in 2017. He serves as co-CEO of tastytrade and appears daily on the tastytrade financial network. @tastytrade