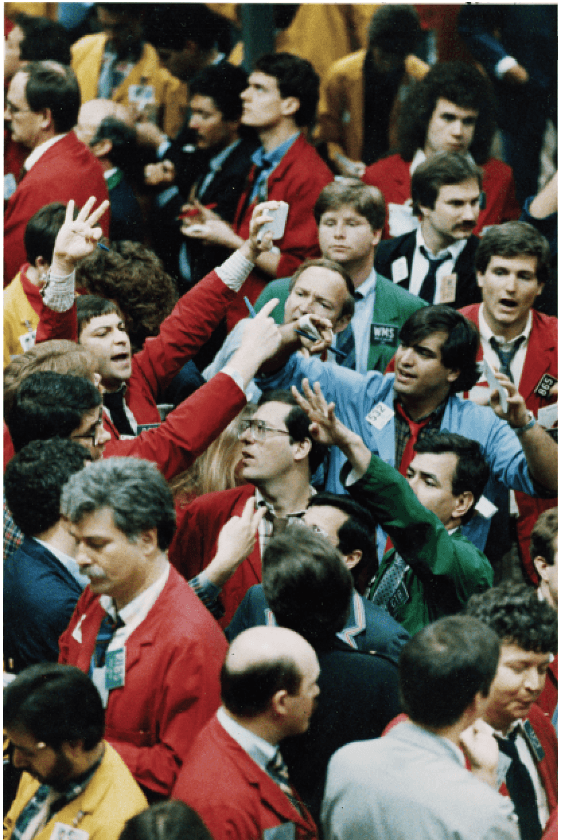

Tales from the Pits

Former floor traders recall their favorite moments from Chicago’s trading floors

From the first moment I saw the trading floor, I knew I had to be on it. And in the late 1990s, Chicago trading floors were the most important pieces of real estate in the country. Every economic statistic, political development and international incident instantly funneled through those rooms, shifting the fortunes of an entire community, from locals to clerks to the newspaper seller out in front of the exchange. The world was moved by the exchange and what happened in it. There was a vital, almost holy atmosphere about

the place.”

— Jonathan Hoenig traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, MidAmerica Commodities Exchange, and Chicago Board of Trade floors from 1996-2000 and is now portfolio manager at Capitalistpig Hedge Fund, a Fox News contributor and the author of The Pit: Photographic Portrait of

the Chicago

Trading Floor.

@jonathanhoenig

A crude IBM trade

My buddy Jules and I were trading partners and we shared a clerk. Clerking on the trading floor was how most new traders got their start in the business. Our clerk’s name was Billy, and on this particularly crazy day Billy had worked his butt off. Although we primarily traded the S&P 100, occasionally Jules and I would put positions on in other stocks and futures. On this particularly busy,

down day, Jules asked Billy to run over to the IBM pit to get a quote on a put spread. He was long and wanted to sell. Just before that, we were chatting about why the market was so weak. The consensus was that it was because crude oil broke to new lows under $10 and was approaching $9 a barrel in a late afternoon free-fall.

Billy, standing near the IBM pit, hand signaled (everything back then was done with hand signals) a $.90 bid for the IBM put spread. At least that’s what Jules thought. Jules aggressively signaled back, “Sell 50!” Billy gave him the fill sign and walked back to the S&P pit. This all happened two minutes before the close.

After the close, Billy told Jules he was price improved on his fill. Jules said great, because he badly wanted out of the IBM position for a profit. Billy snapped back, “What IBM trade?” Things went downhill quickly from there. It turns out Billy heard our crude oil conversion, and with crude oil on his mind he sold 50 crude oil contracts (each contract equals 1,000 barrels) on the all-time low tick of $9.08.

It was a Friday afternoon. I did a goodwill check on Billy over the weekend to make sure Jules hadn’t killed him. He was not a happy camper. Luckily though, the story has a happy ending. Crude opened Monday morning at $8.80, and Jules bought the low and made money on the entire debacle. The crude futures have never traded at that level again.

And no, Billy did not share in the profits.

— Tom Sosnoff traded on the Chicago Board Options Exchange from 1980 to 1999 and is now co-CEO of tastytrade.

Look at the Swiss

When I was a young trader in the Deutsch Mark pit, barely making a living, I spent much of my free time in the Chicago Mercantile Exchange library trying to find some methodology that would give me an edge. Those were the days before computers, when you constructed your own charts with a mechanical pencil. I studied candlesticks, Steidlmeyer and some crazy scheme called the Congestion Theory. Nothing worked, and with every passing day, it seemed that my dropping out of law school to trade was not such a great decision.

One day, I went to see a one of my father’s friends who was a successful trader and whom I had not wanted to bother. He was really nice—gave me a pep talk—and, on my way out, he said, “Take a look at the Swiss franc. It’s an obvious short.” I thanked him and ran to the pit before the market closed and sold five contracts, the largest position I had ever taken. I could barely sleep that night, and when I walked onto the floor at 5:30 the next morning and heard the call in the Swiss was 100 points lower, I could not believe my good fortune. When the market opened at 7:30, unable to contain my excitement, I bought back the five contracts by 7:30:10. I had made $6,250! This was the turning point—the moment my career really began. Then, as it happens, the currencies went into an extremely volatile bear market that began that day and lasted for at least a year, creating a lot of opportunities for pit traders like me.

About six months later, at a social event, I ran into my dad’s friend. We traveled in different circles, and I had not seen him since the pep talk and his life-changing trading tip. I went over to thank him—to tell him how much I appreciated what he had done for me. But before I could open my mouth, he said,

“I hope you held onto your Swiss.” I looked him right in the eye and said with all the bravado of a successful trader, “Of course. Caught the whole move down. Changed my life.” And then, thinking about the five contracts I sold on the first day of a historic bear market and bought back 10 seconds later, I did not remember to thank him.

— David Silverman traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange floor from 1982-1997 and is now CEO of broker-dealer and marketmaker Alpha Trading LP.

Always put a number on it

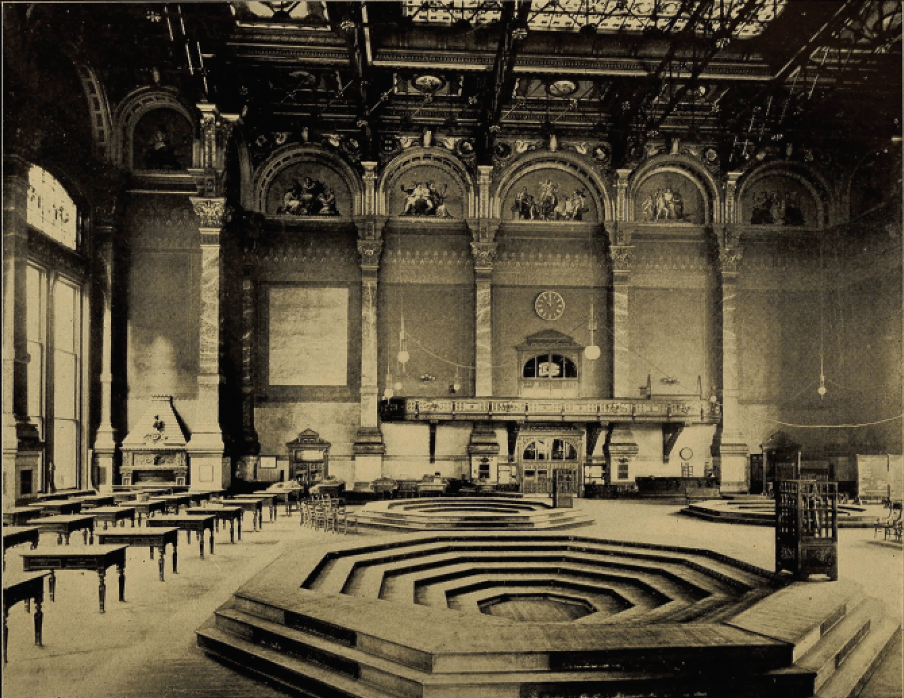

I began my trading career on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in the days when traders used open outcry trading. They conveyed bids and offers by voice in the pit.

A trader would indicate both a direction (buy or sell) and the quantity to trade. For example, someone looking to buy a Canadian dollar contract would announce his intention by verbally bidding “12 bid for 10,” meaning the trader wanted to buy a maximum of 10 contracts at a price of 7610 (usually the first two numbers were dropped for expediency).

This seemingly confusing method of verbalizing bids and offers worked quite efficiently. Strict adherence to these mechanics was the goal, but not often the practice. This played through in a fashion that definitely caught me off guard one day while trading “calendar spreads” in the forex markets.

Every 90 days, traders would “roll” their positions forward, and a portion of the pit was designated the “roll area.” I would actively make markets in these spreads. Typically, a larger order in the spreads would be between 100 and 200 contracts, which equated to an exposure ranging from $10 million to as much as $20 million notional.

One day early in the session, an order filler from one of the larger brokerages came into the spread pit and asked where the bid was for the March-June spread. The first mouth open usually got the trade, so in my zeal to quote the market I yelled out, “6 bid at 7,” putting no quantity qualifier on it. The broker turned to me and said, “Buy 7,000.”

Because I had not put a quantity on my bid/offer, I opened myself up to taking any amount another trader wanted. My spread book in most cases never exceeded two to three thousand spreads at any one time. But in a single trade I was now short a 7,000 spread—my largest exposure ever—all because I was trying to be quickest to the order and forgot to “put a number on it.”

Fortunately, with a cooperative market I was able to cover this position and pull about $10,000 in profit on this luckbox of a trade.

— Pete Mulmat traded on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange from 1980 to 2012 and is now chief commercial officer of the Small Exchange

Feb. 18, 1988.

Your word was your bond

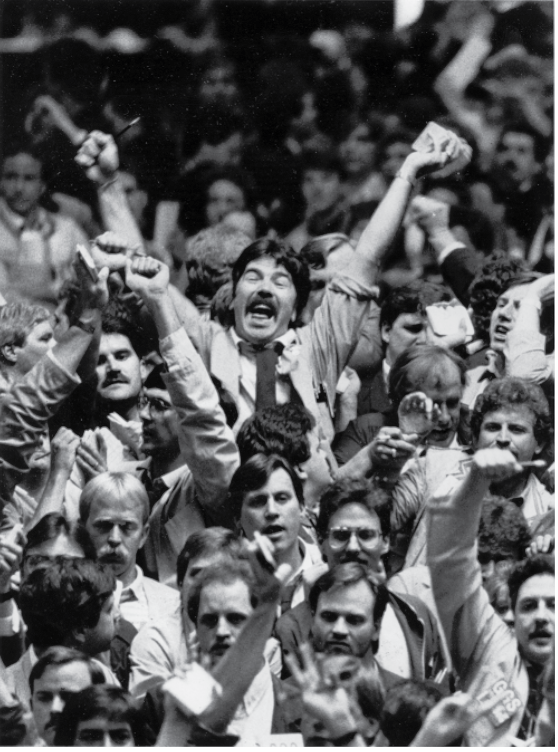

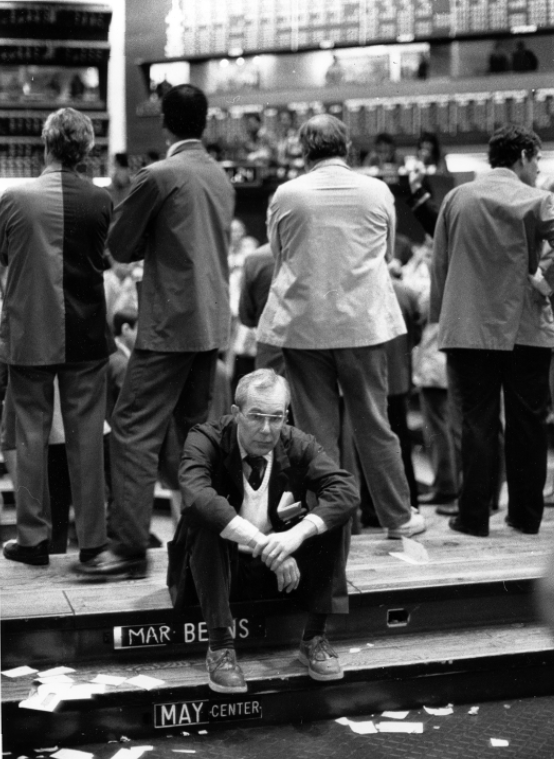

I loved my time on the trading floor, not only for the opportunity to make big money and live the lifestyle that came with it, but also for the camaraderie among the colorful cast of characters who populated the pits.

Traders came from all walks of life. There were Ivy League grads, ex-Israeli Fighter Pilots and engineers. Others had barely graduated from high school. Your pedigree didn’t matter. You had to be fast and aggressive. Often, you had to be humble enough to accept defeat, admit your position was wrong and lock in a loser to minimize risk. Hopefully, you would live to fight another day.

The integrity that I witnessed there was astounding. Your word was your bond. It still amazes me when I think of the number of contracts that were traded amid the chaos and how the vast majority of out trades were settled amicably with words like, “I thought I was buying them, too. If you said I sold them, I take your word for it. Let’s split the error between us.”

Some traders did business unethically, but they didn’t last long. Their fellow traders ostracized them because no one wanted to trade with someone who wasn’t true to his word.

— James Dore traded on the Chicago Board of Trade floor from 1991-2016 and is now director of market surveillance for the Small Exchange. @small_exchange

Think big, think positive, never show any sign of weakness. Always go for the throat. Buy low, sell high. Fear? That’s the other guy’s problem. Nothing you have ever experienced will prepare you for the unlimited carnage you are about to witness. Superbowl, World Series—they don’t know what pressure is. In this building, it’s either kill or be killed. You make no friends in the pits and you take no prisoners. One moment you’re up half a mil in soybeans and the next, boom, your kids don’t go to college and they’ve repossessed your Bentley.

—Louis Winthorpe III, Trading Places (1983)