The Future of Futures

As futures trading evolves, contracts are shrinking; now, a new exchange promises to get even smaller

Becoming a modern investor requires buying shares of stock as the first, fundamental step. That could mean buying 100 shares of Apple (AAPL) or investing $1,000 in a mutual fund.

But that simplicity belies the enormous legal and regulatory apparatus behind those shares of stock or that mutual fund. Without the right infrastructure, stock trading—and especially mutual funds—wouldn’t exist.

Futures, by comparison, are relatively straightforward. Sure, regulations govern futures trading, but an agreement or contract about the price of the future delivery of a product is simpler than ownership in a public company.

That’s why trading futures should become one of the first steps an investor takes, particularly in light of recent innovation in futures products—it’s innovation made possible by the centuries-old relative simplicity of futures.

Stock trading likely began in 1602 when the Dutch East India Company sold shares of ownership to the public. It wasn’t a huge enterprise by modern standards because the company could keep track of only so many transactions with quill pens. Buying stock requires properly transferring ownership, making sure the number of shares isn’t greater than authorized, adhering to accepted accounting practices, paying dividends to the right owners and looking after a lot of other details.

That’s why stock trading came centuries after the Babylonians— and later the Greeks and Romans— traded what would now be called futures on agricultural products. In a largely agricultural economy, the value of buying and selling tons of grain was readily apparent even before it was loaded onto ships or into ox carts.

The Code of Hammurabi included rules about buying and selling goods at a certain price on a future date. Agreeing to pay a certain number of shekels for a big pile of wheat after the next harvest made sense to both the miller and the farmer, and it required not much more than a handshake. Those handshakes occurred for centuries, smoothing trade and helping producers and users get a firmer grasp of their financial future.

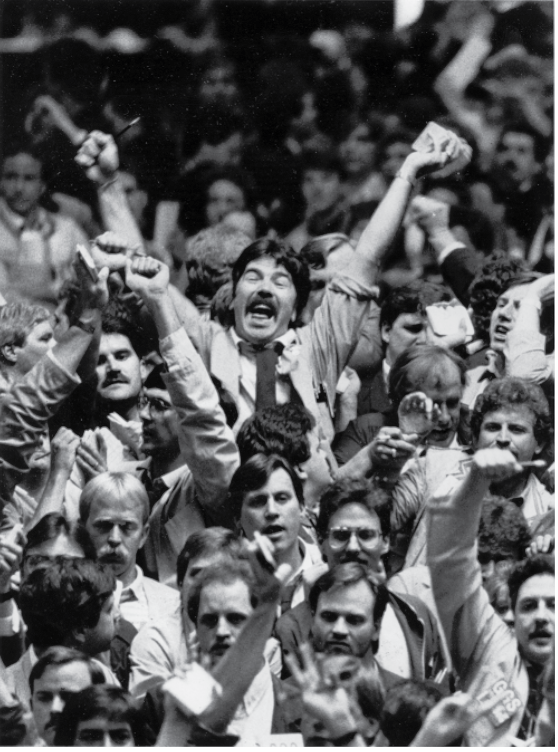

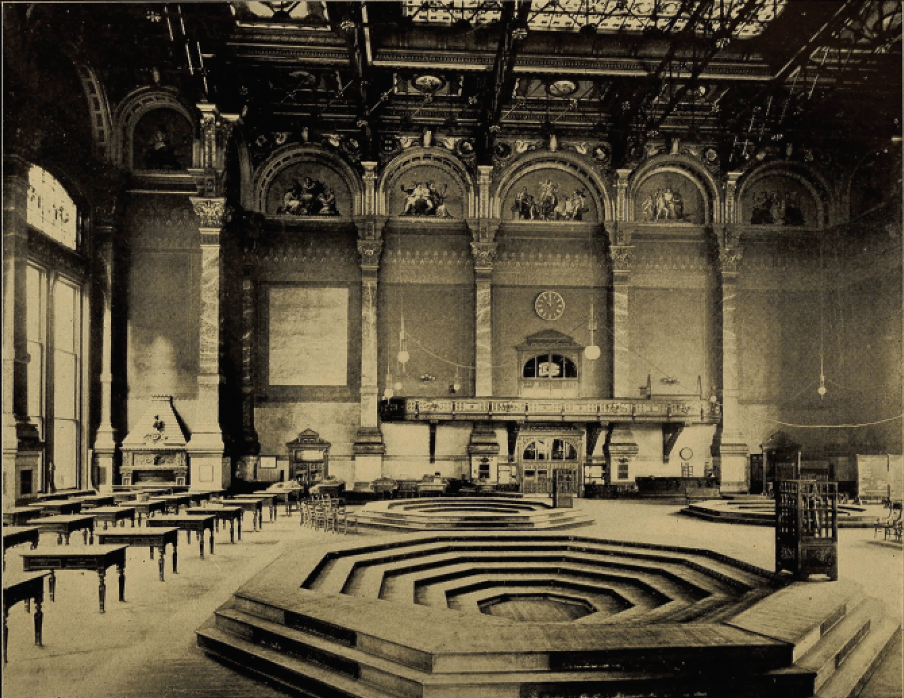

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Japan’s Dojima Rice Exchange began to trade futures more formally, and then in the 19th century both the Chicago Board of Trade and the London Metal Exchange were established to do the same thing in the West. Even though what would become the New York Stock Exchange was established in the late 18th century, stock ownership wasn’t widespread—it was futures prices that influenced economies.

Grain and copper were key commodities, and traders exchanged contracts for huge amounts of those products. That trading provides clues to a certain stage of futures development. A corn future, for example, delivers 5,000 bushels. That’s a lot of corn, and with each bushel weighing about 56 pounds, a corn future wasn’t designed to meet the needs of someone looking to make a batch of succotash. It’s clear that 250,000 pounds is industrial corn.

The same is true for gold (100 ounces), crude oil (1,000 barrels) and bonds ($100,000). Each innovation in futures has carried its industrial past. So, while futures products have exploded to cover just about everything investors want to speculate on or hedge—like equity index futures, currencies, precious and base metals, gasoline, natural gas, interest rates, bitcoin, volatility, and more—they have been “big,” with contracts sized to meet the needs of corporate or industrial users.

Stocks, on the other hand, have always been keyed to the individual investor. It’s always been possible to buy one share of stock instead of the round lot of 100. The arrival of mutual funds in the 20th century enabled investors to buy custom dollar amounts. But innovation in the equity markets has been slow compared to futures, with exchange-traded funds (ETFs) the next big development in the 1990s. And funds and ETFs are just ways to repackage stocks. Anyone who’s ever bothered to read the charter for a fund or ETF got a sense of the underlying complexity, which allows adding fees half-hidden from view.

With equity products consumer-sized and their complexity disguised in legalese that’s largely ignored, Wall Street aggressively marketed stocks, not futures. But that’s starting to change. In the last 20 years, investors have become more sophisticated, and demand for consumer-friendly futures products has grown.

Getting small

Futures are attractive because they enable individuals to speculate directly on specific commodities like corn or crude oil without having to trade an indirect product like stock in a fertilizer company or oil refiner. They enable stock index traders to trade the S&P 500 without the fees associated with funds or ETFs. They’re also capital efficient, requiring less initial capital for a given notional value of risk than a similar equity product.

Still, the industrial heritage of futures means different tick increments and sizes, high margin requirements and funky trading hours. When investors buy 100 shares of Apple or IBM (IBM) or Tesla (TSLA), they make $100 when the stock goes up $1. Not so with futures.

Against this backdrop, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange launched its E-mini S&P 500 futures in 1997, which are one-fifth the size of the standard S&P 500 futures. Those, along with a handful of other E-mini equity index futures, were pretty much the only consumer-sized futures available.

Twenty years later, the Small Exchange was conceived with individual investors in mind. With sub-$1,000 margin requirements, .01 ticks and $1 tick sizes, the Small Exchange futures products are the most accessible and consumer-friendly to date for equity indices, metals, energy, currencies and bonds.

These innovations should level the playing field between stocks and futures for the attention of the individual investor. The Small Exchange’s smaller products, in particular, take advantage of the natural simplicity of futures. That simplicity is passed on to traders. Investors are no longer restricted to a traditional portfolio comprised of highly correlated equities and equity indices that offer no meaningful diversification.

It’s now possible, and affordable, to assemble a portfolio of futures in equities, interest rates, energy, currencies and metals to create real diversity for an account, even with limited capital. That’s not just about trading futures but also about finding a smarter way to build wealth.

Tom Preston, luckbox features editor, is the purveyor of probability and poster boy for a standard normal deviate.