The Genius Guide to IQ

Scores on IQ tests can tell us a lot, but they can’t tell us everything

Does IQ matter? Well, yes and no. High scores on intelligence-quotient tests often correlate with success. But psychologists agree that people amount to more than a single measurement of intellect can capture.

The predictive power and limitations of IQ scores have been apparent almost from the start of intelligence testing at the turn of the 20th century. French psychologist Alfred Binet designed the first tests to calculate a child’s “mental age.” They were administered to identify kids who needed extra help in school.

The testing soon expanded to include adults, and now the tests are calibrated to produce an average score of 100. Most people fall within one standard deviation of the mean with a score ranging from 85 to 115, and the genius level begins at about 140.

At best, IQ scores yield an approximation of intelligence that psychologists characterize as a “snapshot.” Scores can decline as a person ages, and different IQ tests can produce slightly different scores for the same individual.

A slippery subject

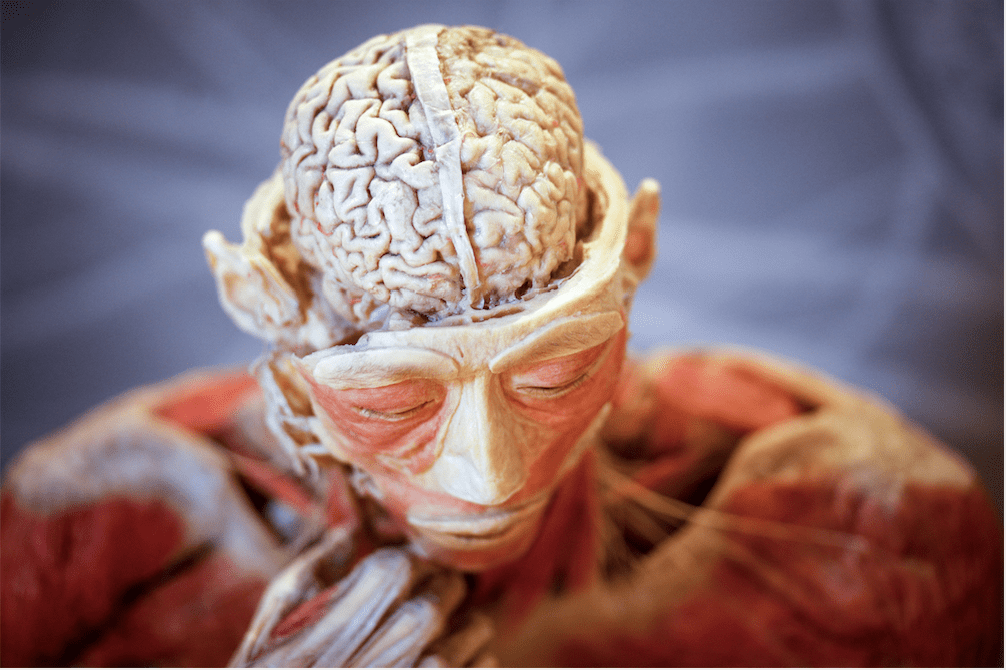

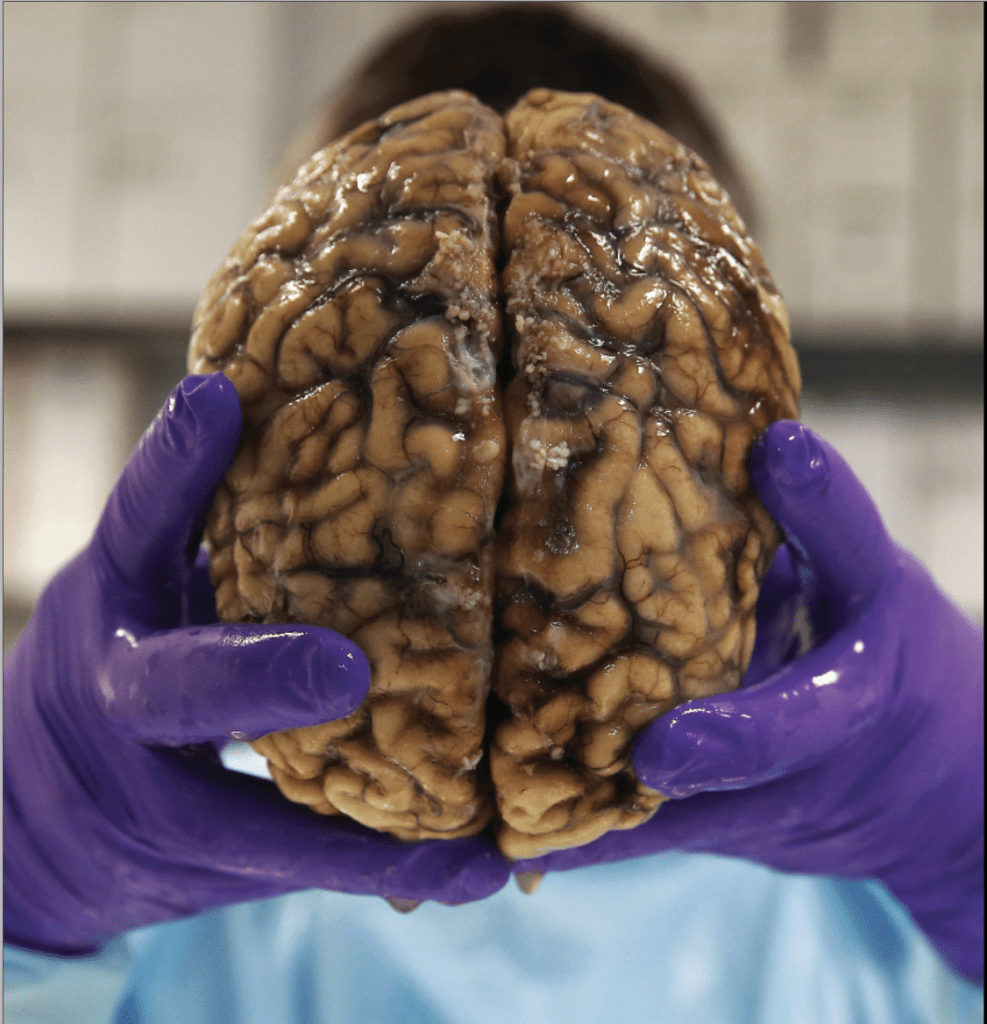

It’s difficult to measure IQ because even after more than 100 years of research, experts still can’t define intelligence. Just the same, English psychologist Charles Spearman proposed in the early 1900s that there’s a general intelligence factor called “g,” which is written as a single uncapitalized letter.

The g factor was originally considered some sort of brain energy or brain deficiency that underlies all human abilities, according to Kevin McGrew, director of the Institute for Applied Psychometrics and a research professor at the University of Minnesota.

“I call it the Loch Ness Monster of psychology” because scholars have written about g for a century and are now coming to the conclusion that it doesn’t exist, says McGrew, who earned the nickname “IQ McGrew” early in his career. “It’s just a statistical artifact of the data,” he says of g. “It emerges from the data but doesn’t represent anything that exists in the brain.”

McGrew explains what he considers the non-existent g this way: “There is no such thing as horsepower in a car engine. We call it an ‘emergent property’ because it emerges from the interaction of all these systems in there working together.”

But Scott Barry Kaufman, a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania (see p. 42 and the sidebar, right), feels confident that his colleagues will reach a balance between overemphasizing intelligence and denying that there’s any such a thing. “In statistics, it’s called regression to the mean,” he says. “It’s a real phenomenon.”

Another phenomenon that arises with IQ scores is their steady 100-year march upward, gaining about three points per decade. It’s called the “Flynn effect,” as documented by James Flynn, a professor who studied at the University of Chicago and taught in New Zealand (see pg. 43).

Scores are rising because the world is changing from the concrete to the conceptual, says William G. Harris, CEO of the Association of Test Publishers. Other experts agree and also attribute the upward trend to improved health, education, nutrition and living standards.

Foretelling the future?

Whatever intelligence might be, it can predict outcomes, according to Charles A. Murray, who wrote The Bell Curve with Richard Herrnstein (see p .42). Murray argues that intelligence is better than parental socioeconomic status or educational achievement at forecasting income, job performance, criminal activity and pregnancy out of wedlock.

Still, a high IQ score doesn’t guarantee a bright future. The word “grit,” meaning “strength of character,” has come into increasingly wide use to describe qualities that lead to success. American psychologist Angela Duckworth describes the phenomenon in her book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance.

What’s more, overreliance on IQ scores as a predictor of outcomes can lead to tragic errors, especially when schools use them as a “gating mechanism” that prevents students from realizing their potential, Kaufman says.

But testing is not going away, Harris insists. Artificial intelligence will find ways to make testing noninvasive and continuous. “It’s going to become effective for instant intervention after diagnostically identifying areas that may need remedial intervention,” he says.

If all of that seems like too much, just take Kaufman’s advice and visit his website, selfactualizationtest.com, to take a test that measures goodness, wonder and awe.

“There’s a wide world out there that lies far beyond knowledge of your IQ score,” Kaufman says, “even though IQ might be an important part of you.”

The Empowerment of “Intellectual Revenge”

Scott Barry Kaufman developed a “screw you” attitude that broke him out of the special education mold and carried him to the highest levels of academic achievement.

“It doesn’t feel good when you’re a child and you’re told that you’re stupid, right?” Kaufman says. “Like, that really upset me.”

Kaufman had an auditory disability that made it difficult to process information in real time. So, his school held him back in third grade and then relegated him to classes for the mentally challenged for the next five years.

In ninth grade, he took himself out of special education and began attending regular classes, where he worked feverishly to prove everyone who had underestimated him was wrong. By his senior year in high school he was getting straight As. Late in his high school career he wanted to switch to gifted education but was disqualified by his score on an IQ test he took at age 11.

Then came college. Based on his SAT scores, the psychology department at Carnegie Mellon University rejected his application. But he got into Carnegie Mellon by applying to the opera department and even won a partial scholarship for his singing ability. He later changed his major to psychology, earned straight As and graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

He went on to earn a doctorate in cognitive psychology at Yale and has taught at Columbia University, New York University and the University of Pennsylvania. He hosts The Psychology Podcast, contributes regularly to Scientific American and has written nine books, including the recent Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization (see p. 42).

He’s made it his life’s work to promote a broader understanding of intelligence.