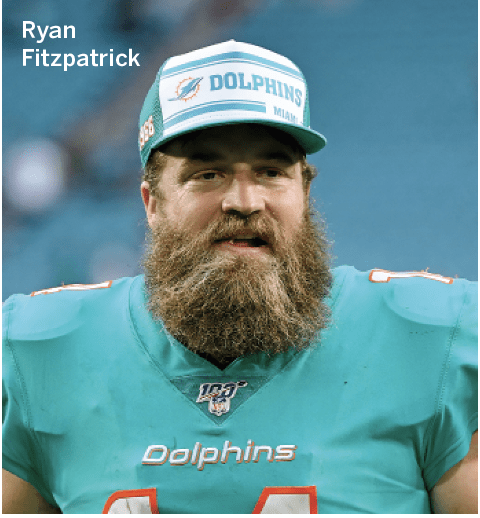

The Smartest Man in America?

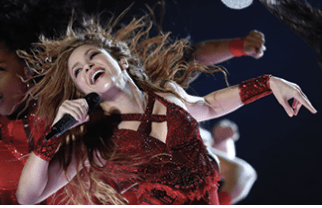

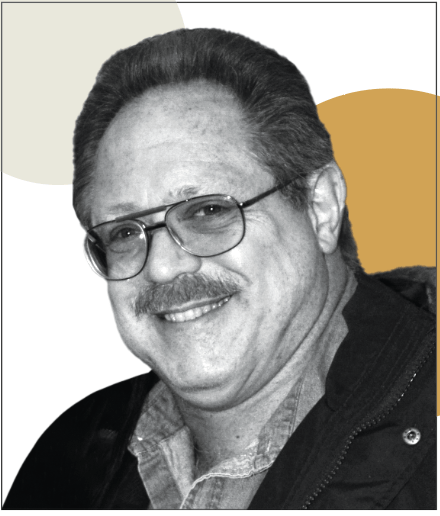

Luckbox leans in with Chris Langan, a man with an estimated IQ score of 200, who breeds horses, ponders the nature of the universe and would never be confused with a rare and delicate hothouse orchid

Some consider Christopher Langan the smartest person in America, but others go even further. They call him the smartest in the world. Either way, the 69-year-old Missouri rancher and philosopher has lived large in ways both good and bad. Despite having an IQ score estimated at 190 to 210 by ABC’s 20/20—or perhaps partly because of it—Langan got off to a rough start in life. He survived a childhood of broken homes and schoolyard bullying. He accuses his third stepfather of abusing him. Dropping out of college, he labored for decades as a bouncer, cowboy, construction worker and forest ranger. Studying on his own, he eventually developed a disputed “Theory of Everything” that uses mathematics to prove the existence of God and the afterlife. Along the way, he’s developed a keen interest in conspiracy theories and stirred controversy with his pointed political views.

Does IQ predict outcomes?

Langan: Up to a certain IQ level, yes. Beyond that level, no … or yes, but in the opposite direction.

If there’s too large an intelligence gap between you and your prospective employer, you’re not likely to get hired. Many employers insist on being the smartest person in the room and don’t welcome competition. Those smart enough to realize your intelligence can make them extra money may not be smart enough to understand your ideas.

There’s an old rule of thumb in psychometrics called the “30-point rule,” usually attributed to psychologist Leta S. Hollingworth. It says that if the IQs of two people differ by 30 points or more (approximately two standard deviations), they’ll probably have a hard time understanding each other. Basically, the higher-IQ subject is not understood because his ideas have too much content for the other to follow, and the lower-IQ subject is not understood because the other perceives errors and holes in his ideas.

Were you ever able to play the IQ card to your advantage—to use it to advance your career or ideas?

That’s seldom the way it works. But on the whole, being publicized as the “Smartest Man in America” has probably been a good thing for me. Specifically, it has been perceived by some as a good reason not to ignore my work. However, it also triggered a “cancel culture” as virulent as that which would later spring up against President Donald Trump.

In the high-IQ world, we sometimes talk about “the danger zone.” This is the IQ range in which one develops overweening confidence in one’s own intelligence but underestimates the intelligence of others and fails to discern the limitations of one’s own intellect. I’ve sometimes tended to attract baseless criticism from danger-zone egomaniacs who fancy themselves the world’s smartest people and claim vast knowledge and expertise that can’t be verified due to their tactical anonymity (use of pseudonyms). They’re a veritable cancer of the internet.

Unfortunately, such trolls are often tolerated as members by social media and special-interest websites that produce valuable content, lending them false respectability. Sometimes this is because those running the forum are discombobulated danger-zone “debunker” types eager to loose the hounds on “cranks,” “crackpots” and “enemies of science.” Unfortunately, it turns out that these terms are readily applied to anyone with a capacity for original thought.

What are the advantages and disadvantges of having a high IQ?

If you have a sufficiently high IQ, you’re better at figuring things out and seeing things coming. Obviously, this can do you considerable good in certain situations. But in some cases, it can make you overthink your situation and can thus interfere with your timing and resolve. Because of the notorious bell curve, which shows that highly intelligent people are much rarer than “normal” people, you can very easily be underappreciated and are more likely to feel isolated or downright alienated.

Do you find it more fulfilling to socialize with people with high IQs? How do they differ from average people?

Obviously, it is more stimulating to converse with people able to understand what you’re saying, if only because they can appreciate your intelligence and respond intelligently. This is why high-IQ people gather together in social groups. However, the level of competition rises in the bargain, leading to jousting, spats and feuds.

Highly intelligent people tend to identify with their ideas, the products of their intelligence, and can become quite belligerent when their ideas are challenged. When you challenge ideas held by a number of them and give them the worst of it, they tend to gang up on you and resort to insult, libel and slander … or at least this is true of the danger-zone “dummies” who proliferate in some sectors of the high-IQ community.

As for super-intelligent people, they tend to be more tolerant of each other’s viewpoints, and try to use them to improve their own understanding.

What tests have you taken? How much did your IQ score vary from one test to another?

I’ve taken several standardized intelligence tests that measure IQ only up to 160 or a bit higher. These tests include the WAIS and Raven’s Advanced Matrices. I’ve broken the ceilings of such tests. I’ve also taken some experimental superhigh-IQ tests that yield higher estimates. (I’d rather not specifically advertise them, but will merely say that they are not without some degree of utility.) It’s important to remember that an IQ test merely takes a “snapshot” of one’s mental ability. A much more meaningful test is that of real-world intellectual accomplishment, especially involving original solutions for important problems. Sometimes, correctly identifying an important problem is itself a major achievement.

You’re self-educated. How do you feel about home-schooling in general?

I’m presently in favor of it. Institutional schooling has always had three main purposes: education, socialization and indoctrination. At one time, the primary purpose of institutional schooling was education, with just a bit of socialization and indoctrination on the side. But this situation has been inverted. Now, PC (politically correct) indoctrination and social engineering often seem to take precedence.

This is largely due to ideological trends and historical movements such as communism, socialism, the Frankfurt School, cultural Marxism, atheism, secular humanism, globalism and other influences that have been pressing on academia and Western society since the first half of the 20th century. Their demoralizing influence has reached a level from which children and young people need to be protected, and from which we all need to defend ourselves.

“If the IQs of two people differ by 30 points or more (approximately two standard deviations), they’ll probably have a hard time understanding each other.”

Would you tell us about your Cognitive-Theoretic Model of the Universe? Has the model met opposition?

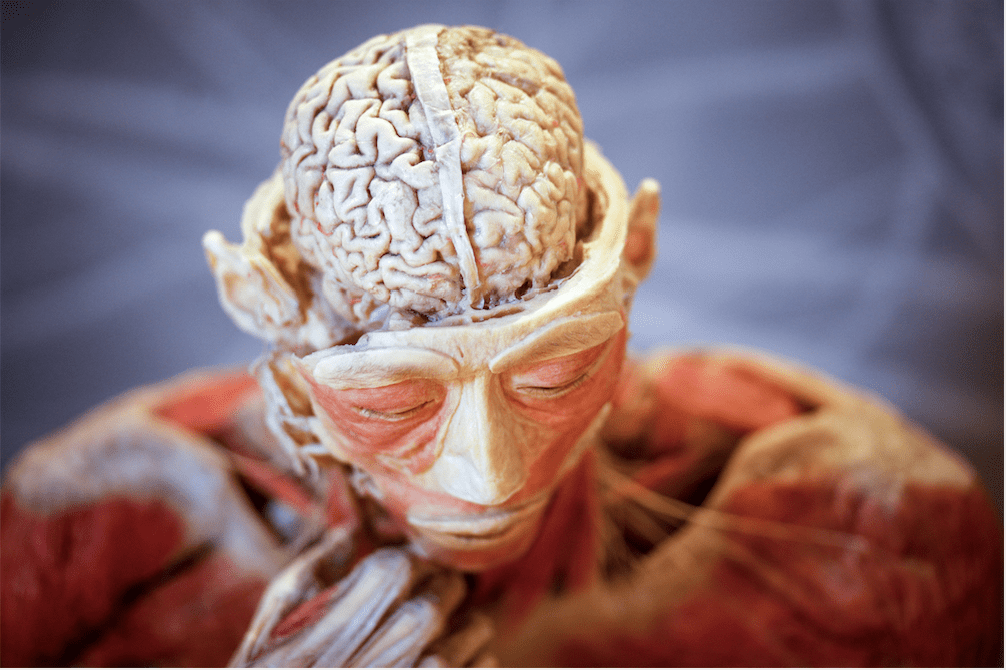

The CTMU, or Cognitive-Theoretic Model of the Universe, is a protean self-reifying theory of reality with a unique structure equating it to reality itself. As such, it is the only viable candidate for an ultimate theory. The “C” also stands for “computation” and “consciousness,” reflecting the multifarious capacity of reality to coherently apprehend and transform itself.

Science now finds itself up against the hardest problems of all time: What is reality? Where does it come from and where is it going? What is life, what is its meaning and what are human beings in the scheme of things? What is consciousness? Is there a God, and if so, what is God’s nature? The CTMU is a highly sophisticated theory equipped with properties that support answers for these questions … answers inaccessible to less-advanced scientific theories and methodologies.

The CTMU is at once a theoretical language, the universe or content of that language, and the model or interpretative mapping relating the language to its content. This structure, which has mental and physical (formal and substantive) aspects, gives it unique properties that make it a true “Theory of Everything.” It can be characterized in several ways: For example, it constitutes a vast, self-contained mind which freely generates its own concepts and percepts; a coherent living language which talks to itself about itself; and a self-replicating “quantum of consciousness.” In spiritual contexts, it is sometimes called “Logos” or “Absolute Truth,” serving as a foundational metalanguage bridging the dualistic gap between science and religion.

One of the most recent and widely discussed scientific ideas about the overall nature of reality is the Simulation Hypothesis, which posits that reality is somehow akin to a computer simulation. In 1989, I published the first application of this hypothesis to a well-defined philosophical problem, Newcomb’s Paradox, and went on to enunciate the “Reality Self-Simulation Principle,” according to which reality models itself for physical self-realization. The CTMU develops this idea to its fullest extent and can thus be described as the ultimate extension of the Simulation Hypothesis and the closest thing that it has to a well-structured theory.

As for opposition to the CTMU, the world is full of people who fancy themselves smarter than everyone else, and the internet provides some of them with an easy way to attack and belittle those who eclipse them or seem to stand in their way. Such people are generally called “trolls.” However, because the vast majority of such trolls fear to put their money where their mouths are and therefore hide behind pseudonyms, they are devoid of credibility. Nevertheless, many users of the internet seem to end up badly misinformed by them.

“The glorified techies who run [Google, Facebook and Twitter] now dominate the internet and are using their dominance to control the information economy, to monopolize social, economic and political infrastructure, and to promote oligarchic world government at the expense of national sovereignty, freedom of expression and human self-determination.”

What new media do you favor? What recommendations would you make?

I prefer media which are not run by people who censor users and promote anti-Americanism.

I’m sure that readers are familiar with the “network effect,” in which the consumers of a product or service contribute to its value—the more people use it, the more value it is perceived to have. The network effect is a golden ticket for those who properly exploit it, including companies like Google, Facebook and Twitter. The glorified techies who run these companies now dominate the internet and are using their dominance to control the information economy, to monopolize social, economic and political infrastructure and to promote oligarchic world government at the expense of national sovereignty, freedom of expression and human self-determination.

The story is always the same. Proprietary technology goes viral and saturates a targeted sector of the World Wide Web. Next comes the IPO. After that, the sky’s the limit! Soon, no one who wants to remain connected and competitive has any choice but to use the viral technology in question, yielding to the demands of its proprietors and passively mirroring their opinions and beliefs.

However, many of us find certain aspects of this standardized ideology false and distasteful, and would rather not be pressured to conform. Accordingly, we prefer social media with proprietors who mind their own business, respect the nation that gave them the economic opportunity to do what they do, and don’t try to cram their own preferences, opinions and beliefs down their users’ throats.

What else should we be saying about your story? After all you’ve been through, what’s most important to you these days?

For me, it has always been about my work. That’s why I became involved in the high-IQ world in the first place—to write for high-IQ community journals, given that academic journals were closed to me—and I’ve never placed a high premium on my life story. In a way that’s unfortunate, as I have a life story that few could hope to match. People love to talk and fantasize about real-world blue-collar geniuses like “Good Will Hunting,” but never seem to know where to look for them. I’m about as real as it gets in that direction. I’ve lived a relatively rough and unsheltered life yet have found myself in the middle of some amazing situations and important transformations.

We’re all familiar with the heartwarming, hope-for-the-future high-IQ stories that periodically show up in the media. Often, such a story features a precocious child who has been carefully nurtured and publicized by his or her parents, is starting college at a ridiculously young age, and hopes to cure cancer and crack the hardest riddles of science. Such children usually end up being spared the necessity of having to make their way from scratch in the real world. Instead, they proceed directly from the computer-equipped nursery to the ivory tower, or, become anonymous cogs in corporate machines run by more practical minds, or like the celebrated prodigy William James Sidis (see below), drop out and squander their gifts on meaningless activities like collecting subway transfers.

This has led to the common impression that intellectual geniuses are rare and delicate hothouse orchids which cannot survive prolonged exposure to the blue-collar lifestyle and hard knocks of the real world, a mold I’ve never fit. Unfortunately, a working-class intellectual is simply more likely than a conventional hothouse orchid to be neglected and “cancelled” by trolls, prigs and hypocrites. Add to this the fact that IQ differences are now regarded as politically incorrect, and the problem is clear.

As for me … well, suffice it to say that the world needs all the help it can get, and I’ve been trying to do my part.

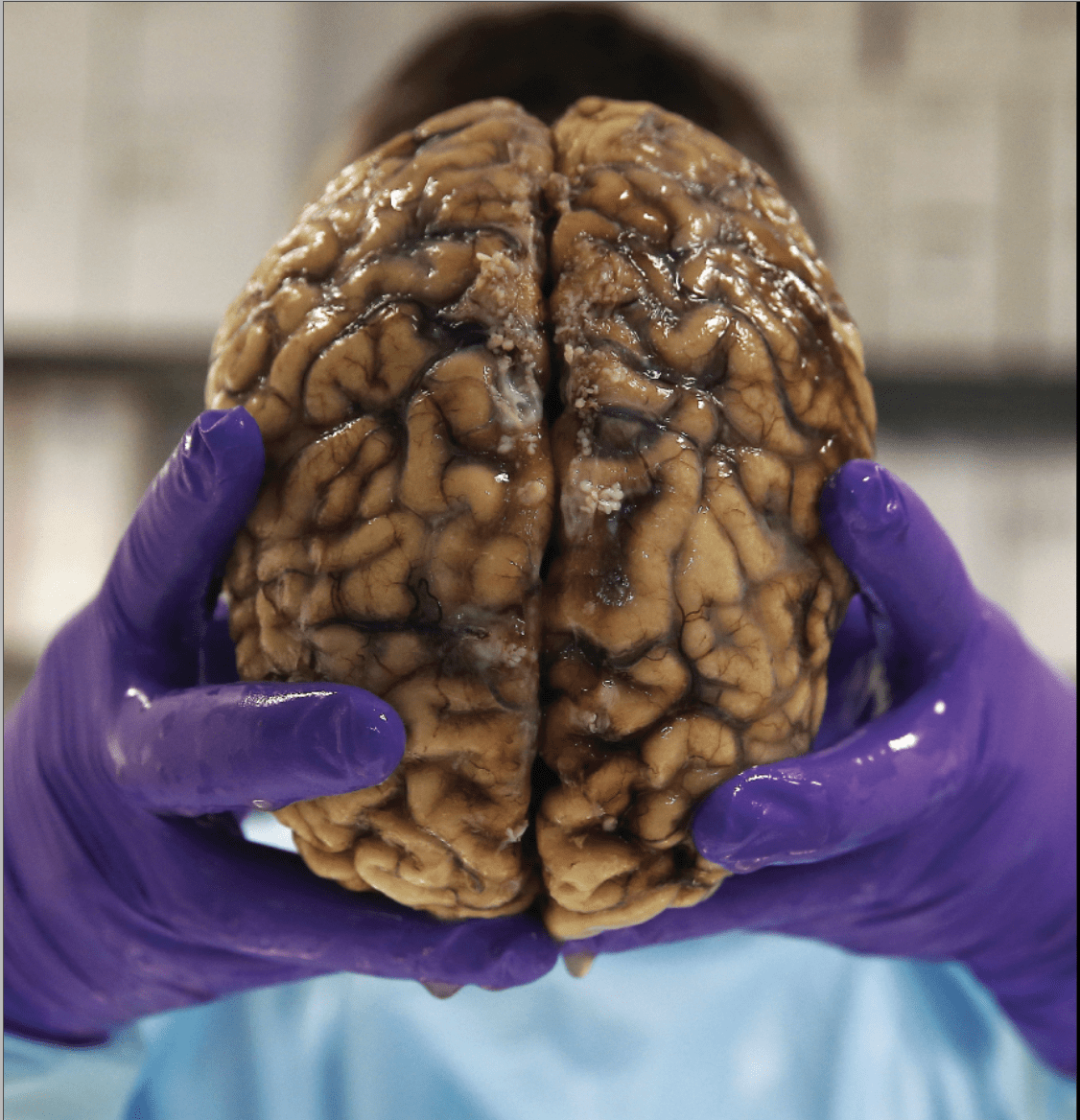

William James Sidis was reportedly reading newspapers by the age of 18 months. He learned 25 languages by age eight, entered Harvard at 11, published a book on the origin of life called The Animate and the Inanimate at 20 and patented a perpetual calendar at 30. But he didn’t maintain that hyperintelligent trajectory. Instead, he wound up in menial jobs and whiled away the time by collecting streetcar transfers. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1944 at age 46. His IQ was estimated to be an extraordinary 250–300.