Who is Hindenburg Research?

The short-seller turns a profit by ferreting out corporate wrongdoing. Just ask Carl Icahn.

- Recently, Hindenburg Research helped sink the stock price of Super Micro Computer.

- It’s not the first time Hindenburg’s research has exposed a company’s problems.

- Hindenburg sells short and then makes a profit when its reports reduce a company’s share price.

A report from short seller Hindenburg Research alleging “recidivist” accounting irregularities at Super Micro Computer (SMCI) contributed to a precipitous fall in the value of the company’s stock.

Shares in Supermicro, as it’s often called, tumbled from $1,229 in March to $416 on Sept. 30. After a 10-1 split on Oct. 1, the price was down to $41 and was still sinking as of this morning.

Hindenburg wasn’t the only entity besieging the San Jose, California-based maker of servers and computer storage. Supermicro is dealing with a lawsuit brought by a whistleblowing former employee and a class-action suit filed by aggrieved shareholders. Meanwhile, it’s coping with an investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice.

But often enough, Hindenburg strikes out on its own to make the case against companies it accuses of wrongdoing. And it stands to profit handsomely from its crusades.

First, Hindenburg takes a short position in the target company’s stock, and then it releases a scathing report that topples the share price. When stock in the company under scrutiny declines in price, Hindenburg and its partners profit.

Authorities, like the Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission, often follow up on Hindenburg reports by initiating investigations of their own or filing lawsuits.

For an example of how Hindenburg operates, click here to link with its exposé of alleged malfeasance at Supermicro, which carries the subtitle “Fresh evidence of Accounting Manipulation, Sibling Self-Dealing and Sanctions Evasion by This AI High Flier.”

A heavy dose of homework

The extensive research Hindenburg performs goes beyond the financial fundamentals to include examination of accounting irregularities, bad actors in management, undisclosed related-party transactions, Illegal or unethical business or financial reporting practices, and undisclosed regulatory, product or financial issues, according to the company’s website.

A look at another Hindenburg report drives home the depth and breadth of the research that’s become the short seller’s stock in trade. A striking example of the company at work came to light for the public in May of last year.

That’s when it took on 88-year-old Carl Icahn, the activist investor who made his name by striking fear in the hearts of executives at companies he attacked. For decades he’s roasted top managers for the way they operate.

Yet, Hindenburg turned the tables on Icahn to the tune of $20 billion.

Yes, $20 billion with a “B”

In a report subtitled “The Corporate Raider Throwing Stones From His Own Glass House,” Hindenburg analysts accused Icahn Enterprises (IEP) of running a Ponzi scheme that paid dividends it couldn’t afford and allowing Icahn to use company stock to back personal loans.

The results? Stock in Icahn Enterprises fell by 75%, losing a total of $20 billion in value. As owner of 86% of the company’s stock, Icahn himself lost $17 billion. What’s more, the SEC charged Icahn with failing to disclose that he pledged his stock as collateral for billions of dollars in loans. For those infractions, he was charged $2 million in fines.

But Icahn’s not alone in running afoul of probes by Hindenburg Research.

Gautam Adani, for example, saw his Adani Group lose $19 billion in market capitalization after Hindenburg in January 2023 published the findings of a two-year inquiry. The subtitle for the report was “How the World’s 3rd Richest Man Is Pulling the Largest Con in Corporate History.”

Here’s an excerpt from the Adani report: “Even if you ignore the findings of our investigation and take the financials of Adani Group at face value, its seven key listed companies have 85% downside purely on a fundamental basis owing to sky-high valuations.”

Highlights of those and other Hindenburg investigations are recounted in detail on the company’s website. By the end of last year, research by Hindenburg and its founders “preceded SEC fraud charges against 63 individuals, Department of Justice criminal indictments against 14 individuals, and foreign regulator sanctions and fraud charges against four individuals,” the site said.

So, who’s behind all this results-driven research?

The origin story

Nate Anderson, the founder of Hindenburg Research, is reportedly approaching the age of 40. He graduated from the University of Connecticut and then drove an ambulance in Israel for nearly a year. Somewhere along the way, he earned certifications as a Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst (CAIA) and a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA).

Anderson worked for some financial companies but has described his experience with them as bland conformity and “run of the mill” analysis of businesses. He later found inspiration when he worked with Harry Markopolos, the investigator who exposed Bernie Madoff’s scandalous investment fraud.

In about 2014, Anderson began preparing whistleblower reports on companies and filing them with an SEC rewards program that paid bounties. By 2017, he was running his own hedge-fund brokerage, specializing in providing fraud reports. But his business reportedly floundered.

In 2018, he started Hindenburg Research, which by now has a dozen or so employees. It’s difficult to track down how much money the privately held company makes by selling short before releasing its reports. A small group of investors supply the cash to support its operations and make short bets on the side, according to published reports.

But it’s not just about the money, the company website declares. “Our aim is to provide critical insights and evidence to the public, market and regulators to effect meaningful change,” it says.

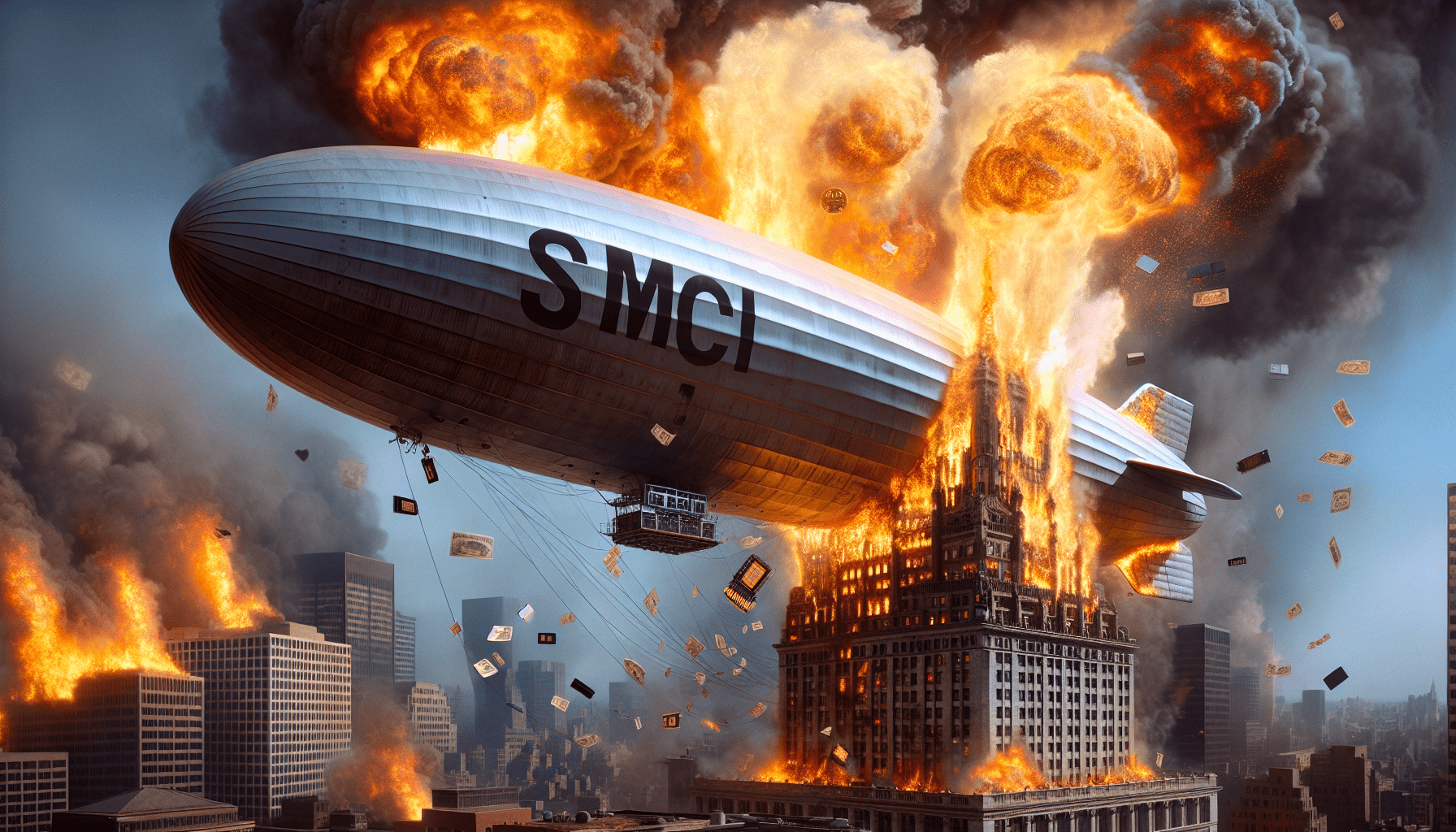

Anderson started Hindenburg Research with a goal he described as exposing “man-made disasters floating around in the market.” The company takes its name from a well-known incident that many would describe as another type of “man-made disaster.”

A German blimp called the Hindenburg burst into flames while trying to dock with a mooring mast in New Jersey in 1937. The tragic spectacle claimed the lives of 13 passengers, 22 crew members and one person on the ground. “Oh, the humanity,” a radio announcer famously sobbed as he witnessed the carnage.

Some might have a somewhat similar if less dramatic reaction to the problems Hindenburg Research exposes to the light of day.

Ed McKinley is Luckbox editor-in-chief.