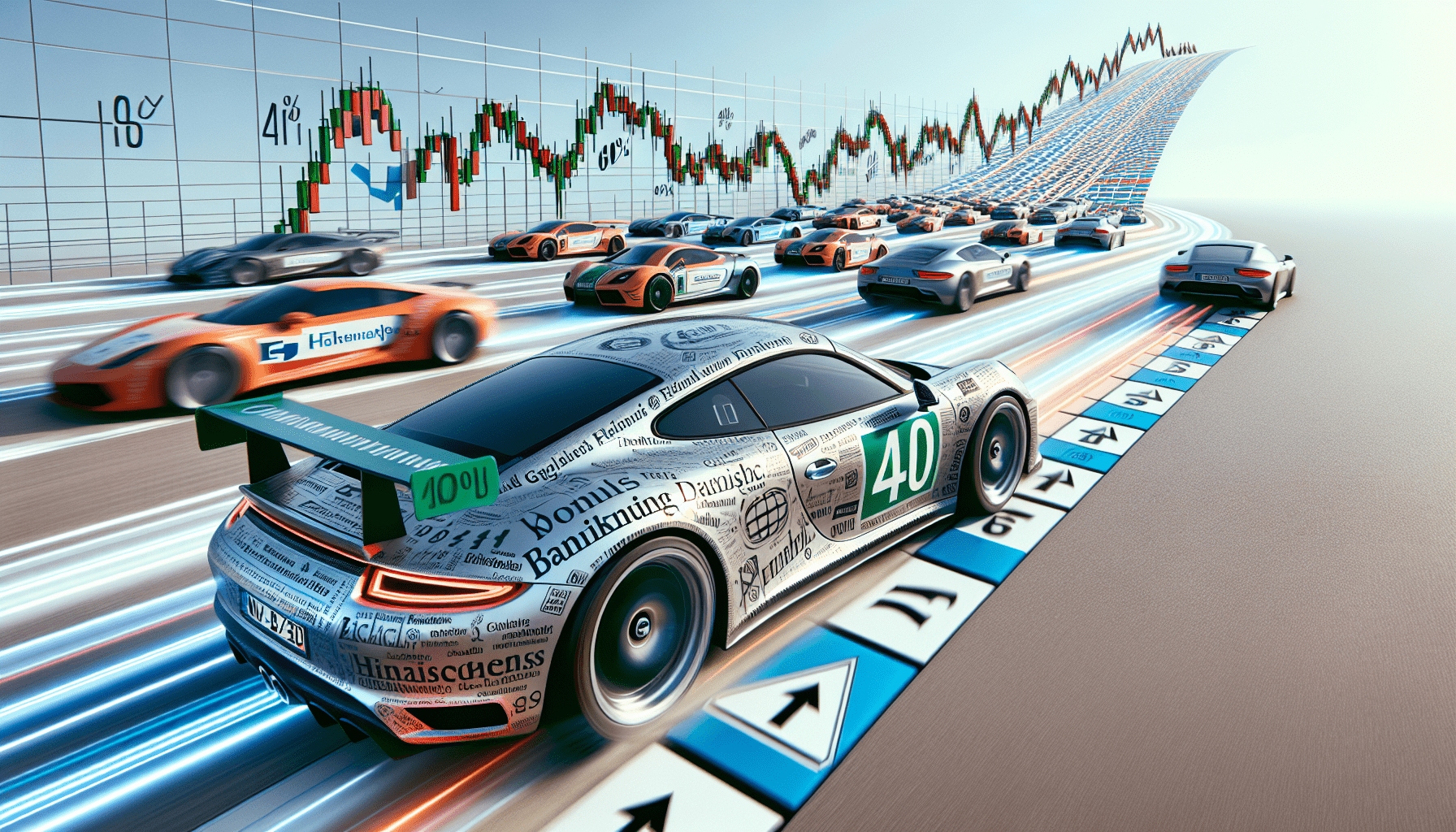

Trading the Surge in Direct Listings

Private companies traditionally debut in the financial markets through a process known as an initial public offering (IPO). But like many business processes in the digital era, this approach is now being pressured by a more streamlined and less costly method: the direct listing.

Interest in direct listings has crescendoed in recent weeks because two big-name entrants to the public markets just chose this approach over an IPO: Asana (ASAN) and Palantir (PLTR).

After debuting on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) on Sept. 30, the stock prices of both companies jumped on robust volume—an increase of 50% for Palantir on volume of 156 million, and an increase of 37% for Asana on volume of 32 million shares.

IPOs and direct listings both allow private companies to enter the public markets, but under slightly different circumstances. IPOs involve the sale of a portion of the company, which requires the sale of newly issued shares. Direct listings, on the other hand, involve the sale of existing shares to the public (i.e. no new shares are issued).

An important distinction between the two is that the sale of new shares through an IPO allows a company to raise new capital, whereas a direct listing does not—at least, that used to be the case, until recently.

Leading up to an IPO, investment banks serve as underwriters of the deal and advise on valuation. They also market the offering and help facilitate the sale of shares to investors.

Unlike direct listings, IPOs require “lock-up periods,” meaning existing shareholders are prohibited from selling shares in the market for a designated period of time. This ensures that only new shares are traded during the public debut, thus avoiding a potential tsunami of existing shareholders dumping stock.

During a direct listing, existing shareholders, such as employees and angel investors, can sell their shares immediately. On the first day of trading, all transactions in the market actually depend on the sale of shares by existing shareholders because no new shares are issued.

One can see how the ultimate avenue selected for a public offering—an IPO versus a direct listing—depends heavily on the exact circumstances of the company in question. It should be noted that prior to Asana and Palantir in 2020, there were only two direct listings on the NYSE during the previous two years.

Notably, those debuts also involved well-known tech companies: Slack (WORK) and Spotify (SPOT).

Generally speaking, companies pursuing direct listings often share one valuable characteristic: name recognition. That’s because unlike IPOs, there’s no marketing assistance provided by an investment bank during a direct listing, which means significant organic demand needs to exist for the shares.

A direct listing might therefore be relatively more attractive to well-known companies because the process allows them to avoid paying sky-high IPO advisement fees. That’s not to say advice on direct listings is free, but the cost for such services is greatly reduced as compared with a traditional IPO.

For example, Slack paid its direct listing advisers about $22 million when it went public in 2019. By comparison, the total fees paid by Snap (SNAP) to a consortium of 26 banks when it went public in 2017 amounted to roughly $85 million.

Interestingly, Airbnb is expected to tap the public markets soon and purportedly has chosen to do so via an IPO—likely because the company is seeking to raise nearly $3 billion in new capital, implying a total company valuation of roughly $30 billion.

After that, the gaming company Roblox is expected to go public, but Roblox has yet to announce whether it will do so using an IPO or a direct listing.

Leaders at Roblox are likely digesting an important rule change recently approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). As of Aug. 27, private companies going public via direct listing will now have the option to raise new capital.

This is a significant change, and it could shake up the existing IPO system controlled by Wall Street. The speed of disruption, however, may be slow. As noted previously, companies typically require widespread recognition in order to unlock a successful direct listing.

In the short term, that means the stratification between the “have” and “have-nots” on U.S. stock exchanges could become even more pronounced.

Going forward, lesser-known companies from outside the tech sector might be forced to pay exorbitant IPO fees in order to access the investor networks of investment banks, while high-flying tech companies are able to more seamlessly navigate the private-to-public transition via less costly direct listings.

Investors and traders may want to monitor the public debut of Roblox in the coming weeks for further insight into how the private-public transition could shift in 2021 and beyond.

To follow all of the daily action in the financial markets, including newly listed shares, readers are encouraged to follow TASTYTRADE LIVE weekdays from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m. Central Time.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.