Gas Price Gouging or Grandstanding

Some politicos blame greed for soaring prices at the pump, but petroleum industry analysts search for a deeper cause

American consumers are paying a lot more than usual for gasoline, but economists don’t lay the blame on

price gouging.

The market is driving up prices because D.C. politicos banned crude oil imports from Russia—the third-largest oil producing nation—in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine.

But President Joe Biden and a lot of members of Congress don’t see it that way.

“American oil and gas companies should not—should not exploit this moment to hike their prices to raise profits,” Biden declared during a Feb. 24 speech at the White House.

Even if they were overcharging, there’s no federal law to stop them. Yet Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Rep. Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., are joining a chorus of lawmakers calling for action.

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., and 31 other members of Congress, sent a letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer demanding an investigation into “illegal profiteering, anti-competitive business practices and price gouging within the oil and gas industry.”

They plan to hold public hearings to question industry leaders, an approach that doesn’t make sense to Boston University professor Robert Kaufman of the Institute for Sustainable Energy.

“The world price for oil is set on several heavily traded exchanges where there are lots of buyers and sellers and they set the price for crude oil,” Kaufman contends.

Oil-dependent industries, like agriculture, plastics, chemicals, homeopathy and healthcare, compete for every barrel during a war and supply crunch, he notes.

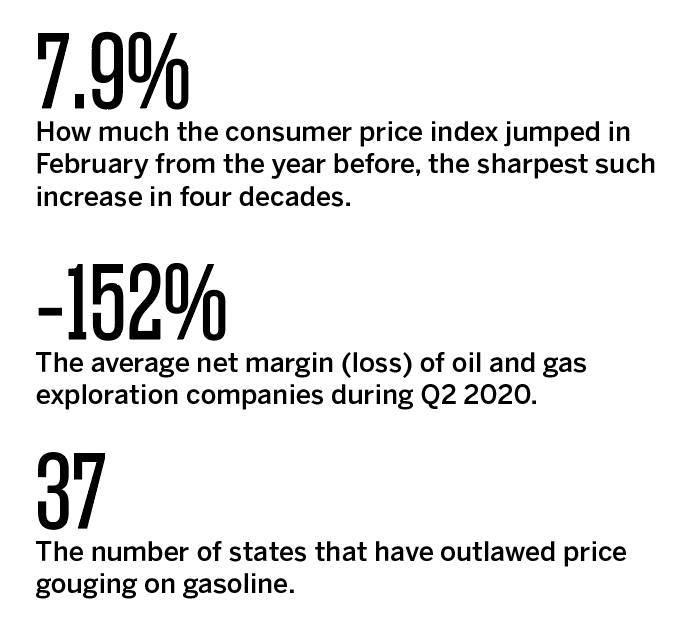

Still, laws against taking advantage of scarcity are on the books in 37 states, Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the District of Columbia. Most of the statutes concern shortages caused by natural disasters or other emergencies. In most states, watchdogs step in when they see evidence of price gouging.

Instead of drafting similar legislation at the federal level, elected officials of every political persuasion prefer to place blame.

Democrats plan to question oil company CEOs publicly about prices that are actually set by global markets and international traders.

Republicans will continue to blame Biden for a market-driven price his administration can’t control. Meanwhile, the GOP is seizing the opportunity to sign up voters at gas stations.

And the independents? They’re just trying to drive to work.

“Come on, man”

Twenty-four of the top oil and gas companies made a record $174 billion in profits in 2021 (these are nominal figures), according to The Guardian. But a deeper look into macroeconomics shows how price volatility and drilling incentives affect an energy company’s bottom line.

The average price margin of oil and gas companies was 4.92% in 2021 as the industry rebounded from losses during the COVID-19 outbreak, according to CSIMarket. However, profit margins are volatile because commodities experience sharp price swings.

During the surge in prices in Q4 2021, the sector enjoyed net margins of 31.3%.

In Q1 2021, the sector experienced net margins of -21%. In Q2 2020, when producers had to pay $32 to have someone take crude away from them from the delivery point in Cushing, Oklahoma, net margins were -152%.

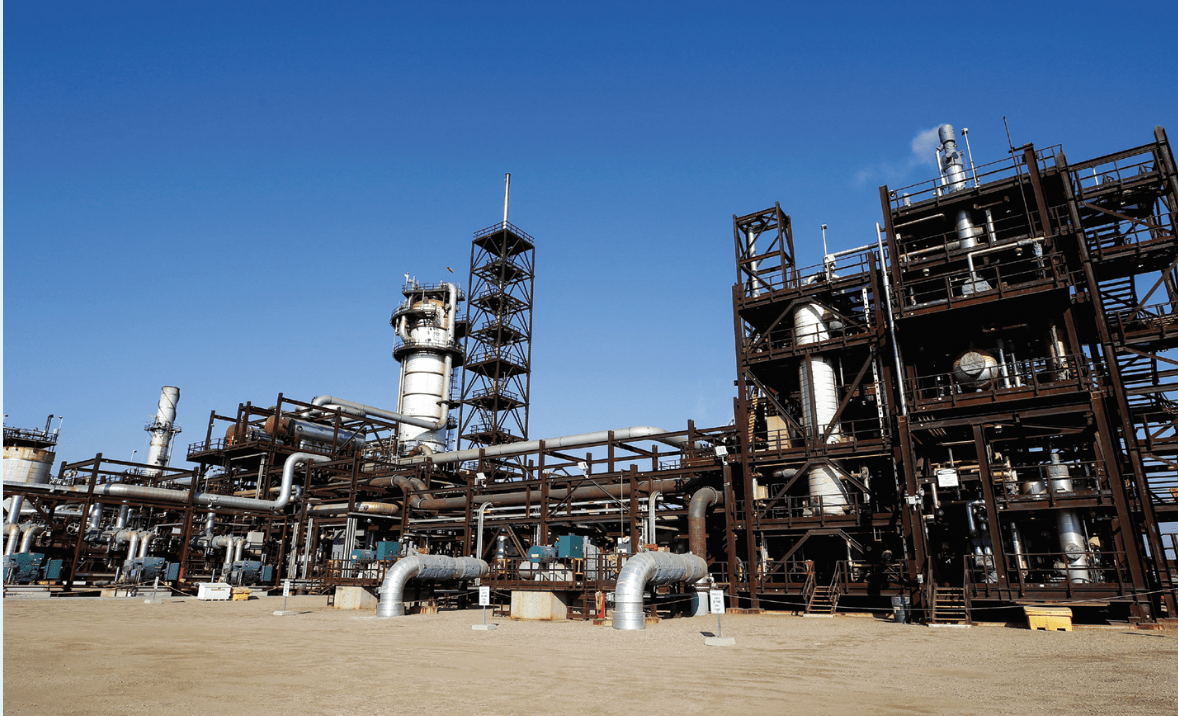

The U.S. energy supply chain is complex.

Oil companies pump crude from the ground and then push it through a multi-dimensional system of pipelines, storage facilities and refineries. Once gasoline leaves the refinery, it’s piped to massive storage containers. Then it’s hauled by trucks (which use increasingly expensive diesel fuel) to gas stations where it’s stored underground in 20,000-gallon drums.

It’s quite a journey from the oil field to an SUV.

There’s a lag between a change in the cost of crude oil and a change in the price for gasoline at the pump. If oil prices decline, gas stations pay a lower price for refined gasoline once it passes through the supply chain. It just takes time. The gas that station operators purchase from refineries typically was refined weeks or even months earlier.

Companies aren’t gouging

Critics accuse companies like ExxonMobil, Shell and Chevron with gouging at the pump, but about 60% of stations branded with the industry’s big names are actually independently operated, according to the National Association of Convenience Stores, a trade group for the convenience and fuel retailing industry.

Those operators buy gasoline from the branded oil company at wholesale and pay marketing royalties. Unbranded operators buy gasoline wholesale and shop for the best price. Although unbranded gas stations tend to have better margins, they can face higher prices when supplies tighten.

Most independent operators (57.1%) own just one store and thus face fierce competition in local gasoline markets, especially in high-traffic areas. State regulators step in if they suspect anti-competitive practices or collusion. And customers drive to a nearby competitor if prices are a few cents lower.

The biggest surprise about gas stations is that they barely make money selling gasoline.

About 80% of gas stations in the U.S. are convenience stores that happen to sell gasoline. IBISWorld, a firm that researches companies, says gas stations make an average net margin on gas and diesel fuel of just 1.4%. Compare that with retailing’s pre-pandemic net profit margin of 5%, as calculated by financialrhythm.com. If a gas station makes a net profit of $0.07 per gallon on 4,000 gallons per day at $5 per gallon, that’s a total daily profit of $280.

On the other hand, merchandise sold inside gas stations represents 30% of revenue and 70% of profit.

The biggest sellers in gas stations and convenience stores include cigarettes, soda, beer and food service offerings

like those spinning hot dogs and the microwave nachos.

So, if higher gasoline prices don’t kill you, the menu will.

Fact or False?

Persistent high gas prices don’t prove price gouging—and neither do comparisons to 2008 gas prices.

Experts said it takes time for gas prices to respond to drops in crude oil costs, and that’s not necessarily indicative of price gouging. The post’s numbers are cherry-picked; the difference in prices isn’t as great as it suggests.

The current situation differs from 2008 because increased labor costs, the pandemic, additional taxes and inflation were all already contributing to rising gasoline prices before Russia invaded Ukraine in February. Direct comparisons lack important context, experts said.

We rate these posts False.

—Politifact