New Tax on Corporate Buybacks

Corporate stock buybacks can boost the value of a company’s underlying shares, but they can also synthetically inflate a company’s earnings per share.

With Q1 earnings season in full swing, some recent corporate announcements have served as a reminder that it’s also “buyback” season.

In this context, buyback refers to share repurchase, which is when a company buys back some of its outstanding shares to reduce the overall net share count.

Buybacks are often announced during earnings season, along with quarterly dividends and other important corporate actions.

Just this past week Alphabet (GOOGL) announced that its board of directors had authorized $70 billion in new share repurchases. In February, Meta (META) announced $40 billion in buybacks.

The Meta announcement was especially interesting because the company has laid off nearly 20,000 employees since last November, but apparently still has an extra $40 billion lying around that it can spend on its own stock.

That’s the thing about buybacks, they’re a bit of a lightning rod—and even more so in recent years.

What is a stock buyback?

In basic terms, a buyback occurs when a company buys its outstanding shares from existing shareholders, or out on the open market.

A buyback represents one potential outlet for extra corporate cash. Instead of a buyback, a company might elect to pay (or increase) a dividend, invest in ongoing operations, or purchase another business.

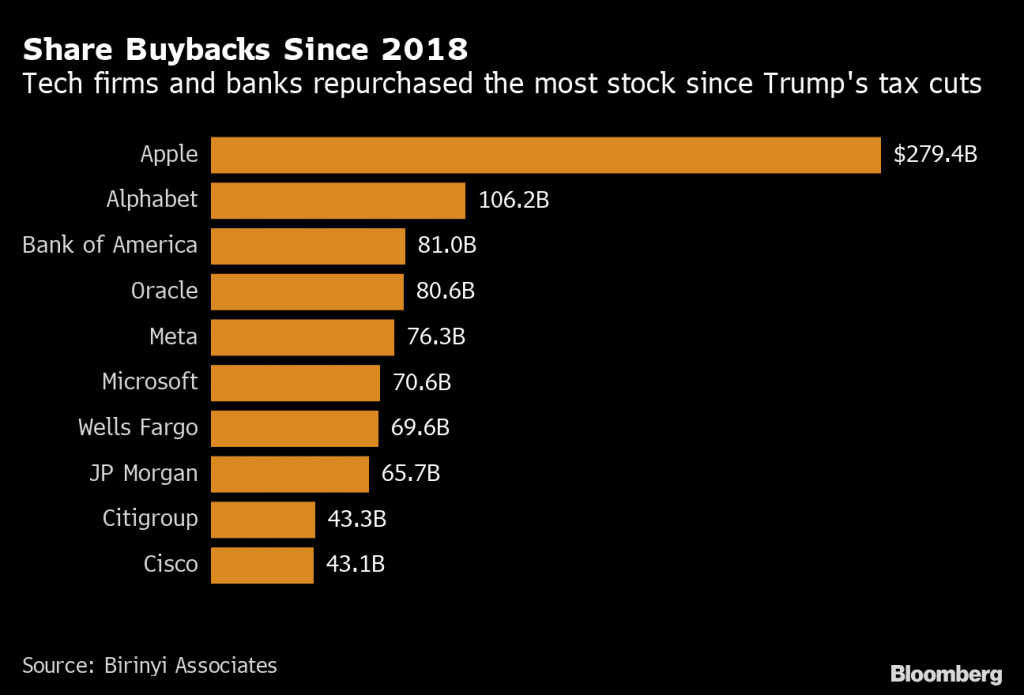

Buybacks have been increasingly popular, as evidenced by the $4 trillion that companies listed on U.S. exchanges have spent on buybacks in the last five years or so. As highlighted in the graphic below, companies from the technology and financial services sectors have been the largest buyback practitioners since the start of 2018.

One reason that companies execute stock buybacks is to try and boost the value of their underlying shares. This premise rests on the basic law of supply and demand. If there are fewer shares outstanding, those shares are theoretically more valuable, all else being equal.

However, another big benefit of a buyback is that it can synthetically boost earnings per share (EPS), assuming the current level of profitability is sustained going forward. Earnings per share is calculated by dividing a company’s net profit by the total number of outstanding shares.

So, if net earnings are $100 and there are 100 total shares outstanding, that equates to $1 per share in earnings ($100/100 = $1). Now imagine a company repurchasing 50 of those outstanding shares.

Assuming that net earnings are sustained, the EPS figure basically doubles, because $100/50 is now equal to $2 in earnings per share. That’s why corporate buybacks are sometimes referred to as “window dressing,” because the earnings figure can improve without any material change to the company’s underlying operations.

Opposition to stock buybacks

One of the most common arguments against buybacks is that the money spent on repurchasing shares would be better spent by investing in the underlying economy, which in turn would theoretically boost employment opportunities for American workers.

An example of this would be if Alphabet elected to invest in a new division of the company, instead of buying back $70 billion worth of its own stock. On the other side of the aisle, proponents of buybacks argue there’s room for both internal investment and share repurchases.

Another common criticism is that stock buybacks are self-serving for corporate management. In the modern corporate environment, many executives and managers are compensated with stock and stock options.

As such, any action that increases the value of those securities theoretically benefits those employees. However, one could also argue that a buyback benefits all shareholders, and that executives and managers typically make up a small percentage of overall stockholders.

In the wake of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis, buybacks were cast in a negative spotlight because some of the banks that went bust during that calamitous period had been aggressively buying back their own shares in the years and months preceding the crisis.

For example, Citigroup (C) repurchased roughly $20 billion of its own stock from 2004 to 2008. But by the end of 2008, the company required a $45 billion government bailout to remain solvent. Along those lines, Lehman Brothers bought back roughly $4 billion of its own stock not long before it went bust in fall of 2008.

These days, Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY) finds itself in a similar position. From 2004 through 2023, the home goods company bought back nearly $12 billion worth of its own stock.

It seems like that money was poured down a drain, though, because on April 23, Bed Bath & Beyond was forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. One of the biggest reasons for the insolvency is the company’s crushing debt load, which is above $5 billion.

Corporate management at Bed Bath & Beyond was buying back stock as recently as 2022, when the company’s stock was flying high amid the meme stock craze.

These examples obviously benefit from the luxury of hindsight, but they illustrate the potential risks associated with buybacks.

Buyback supporters might argue that the aforementioned companies were doomed anyway, and that other uses of those funds—business investments or corporate acquisitions—would have been equally wasteful.

Inclusion in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act

Due to their contentious nature, buybacks have become a hot topic in Washington, D.C.

Back in 2019, the Reward Work Act sought to limit open-market stock buybacks, but the legislation ultimately failed to pass the U.S. Senate.

That said, public outcry over buybacks has persisted, and as a result, a new tax on buybacks was included in last year’s Inflation Recovery Act. As of Jan. 1, 2023, the new legislation mandates that a 1% excise be applied to all stock buybacks.

The caveat is that the excise tax only applies to net repurchases. Due to the existence of stock-based compensation plans, many companies create new shares on an annual basis. According to the new legislation, the tax only applies to net repurchases (stock repurchases – new shares created).

So, if a company issued $100 million worth of stock for the purposes of compensation, and bought back $150 million worth of stock, the company would only be taxed 1% on the $50 million difference ($150 – 100 = $50).

Under the new law, repurchased shares that are contributed to an employer-sponsored retirement plan are exempted. If a company’s total annual stock repurchases do not exceed $1 million, those repurchases are also exempt from the tax.

The purpose of the tax is to encourage companies to invest capital in their own operations, in dividends, or in business acquisitions, which provide a more tangible benefit to the underlying economy. And going forward, stock buybacks will undoubtedly continue to draw both criticism and praise in the court of public opinion.

Prior to the inclusion of the new tax in the Inflation Recovery Act, many experts had predicted that 2023 could be a record year for buybacks. Share repurchases have slowed this year, but not by much. According to LPL Financial, total buyback spending is expected to hit $900 billion this year, which is only $22 billion less than last year.

In February, new legislation was introduced in the U.S. Senate, the Stock Buyback Accountability Act of 2023, which proposes increasing the excise tax on public stock buybacks from 1% to 4%. An associated report compiled by the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business estimates that by increasing the excise tax to 4%, the U.S. government would bring in an additional $265 billion in tax revenue through 2032.

For more context on stock buybacks and their impact in the financial markets, check out this installment of Let Me Explain on the tastylive network. To follow everything moving the markets during Q1 earnings season, tune into tastylive, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastylive or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.