Facebook Advisor Turns Tech Adversary

Seasoned investor Roger McNamee, an early proponent of Facebook and a mentor to Mark Zuckerberg, now advocates curbing the abuses of the internet’s tech giants.

By any standard, Roger McNamee’s record as an investor in the private and public markets has been extraordinary. After earning an MBA at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business in 1982, McNamee joined T. Rowe Price as an analyst. He led the firm’s Science & Technology fund to 17% annual returns through private investments in pre-IPO high-flyers Electronic Arts and Sybase, which was later acquired by SAP. In 1991, McNamee co-founded Integral Capital Partners with venture capital heavyweights Kleiner Perkins. He was a founding partner of the leveraged buyout firm Silver Lake Partners in 1999 and co-founded Elevation Partners with U2’s Bono1 in 2004.

Elevation invested early in Facebook, and McNamee served as an advisor to co-founder Mark Zuckerberg, famously dissuading the then-22-year-old CEO from accepting a 2006 offer to sell the young company for $1 billion. That same year, McNamee introduced Zuckerberg to Facebook’s eventual COO, Sheryl Sandberg, former vice president of global online sales and operations at Google.

McNamee continued to advise, support and advocate for Facebook’s ever-expanding market position and leadership team—until he became increasingly concerned with the frequency and amplification of disinformation emanating from the platform during the 2016 presidential campaign. When the Cambridge Analytica story broke in late October 2017, McNamee described his reaction this way: “Kaboom…that changed everything.”

In January, McNamee published the New York Times bestseller, Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe2, in hopes of increasing public awareness and spurring legislative action regarding issues that Facebook, Google, Amazon and other tech giants represent. He calls those companies “the greatest threat to the global order in my lifetime.” He takes their actions so seriously that he has abandoned his career in finance to become a full-time activist for privacy reform.

In late August, luckbox sat down with McNamee for his take on the continuing saga of Big Tech abuses.

How would you assess current efforts to regulate anti-competitive and data privacy practices by Google, Amazon and Facebook?

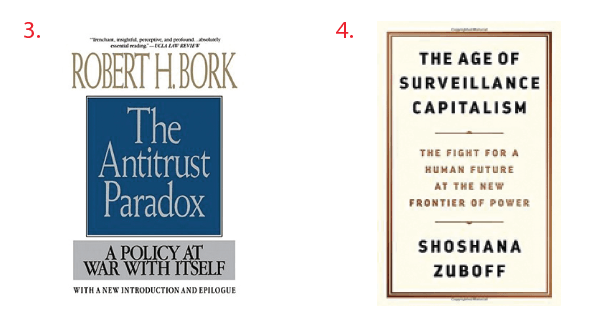

I would describe them as nascent and filled with promise. Beginning in 1981, the United States altered its formula for antitrust regulation according to the principles of the Chicago School, as described by Robert Bork in his seminal antitrust treatise, The Antitrust Paradox3.

Those rules essentially eliminated restraint of trade, anti-competitive practices and conflicts of interest as variables to assess in an intervention, replacing them with a single metric of harm to consumer welfare, namely price increases.

The internet platforms have, until recently, succeeded in convincing regulators that their products are free. It’s only in the past year that an alternative model has entered the conversation. The business model of internet platforms is a barter of services for data, and in such a transaction, data is the currency.

So, if you’re trying to determine consumer harm—to measure whether they are increasing the price—you look at the change in value of the services rendered versus the change in value of the data given up by consumers. The average revenue per user has been rising fairly rapidly for more than a decade. This suggests consumers may well have been harmed.

But antitrust covers only one of the three harms from internet platforms: The damage they cause to competition and innovation. The other harms of internet platforms relate to public health, democracy and privacy.

Those are beyond the scope of antitrust regulators and may require new legislation. There’s a growing awareness in both political parties that something needs to be done. This is a massive change from two years ago, and bills in development focus on privacy, which is as good a place to start as any.

Has your own perspective evolved since you wrote Zucked?

For me, the biggest change during the last 12 months has come from reading Professor Shoshana Zuboff’s book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power)4, which gave me the data for a deep understanding of how the business models of Facebook, Google, Amazon and Microsoft are the root cause of these troubling issues.

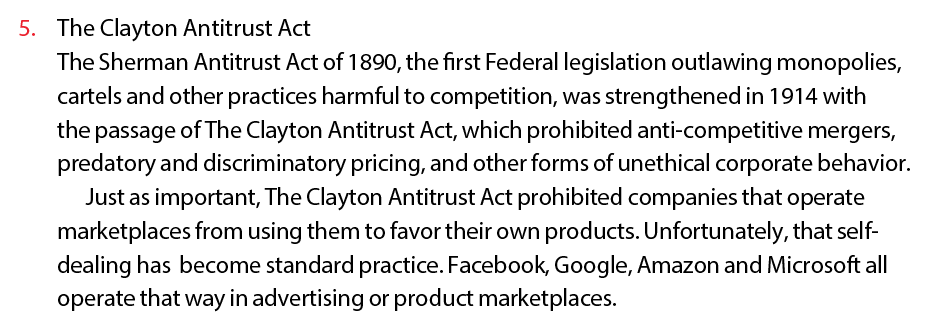

We need for antitrust to create competitive alternatives. The other path is to use The Clayton Antitrust Act5 and the Federal Trade Commission Act, which could prevent or unwind anti-competitive mergers. You could use it to force Google to divest Waze, Amazon to divest Whole Foods, and Facebook to divest WhatsApp and Instagram.

Is the general public sufficiently engaged on this topic?

People recognize something’s not right here—that they may have been deceived by internet platforms.

Some younger people say, “Hey, I’m a digital native. I love these services. I don’t mind trading my private data to get them. And I’ve done nothing wrong, so I have nothing to fear.” My response is that all of those points can be true and not relevant because, increasingly, these platforms harm innocent victims.

Think of it this way. As Zuboff says, Google is in the business of selling behavioral predictions with some degree of certainty attached. That’s a new type of ad market and it’s unbelievably valuable.

How does the business of behavioral predictions work? It starts with products that are convenient. We trust them and expose our entire life to them. Convenience is like a drug, and we always crave more. Platforms gather all the data we give them and combine it with financial, healthcare and location data they buy from brokers and other corporations to create a data voodoo doll that describes our online lives.

Consumers are curious about this issue, but we don’t yet see them rising up. Doubts are creeping in, but they still crave the convenience and utility of internet platforms. We are still in the early days.

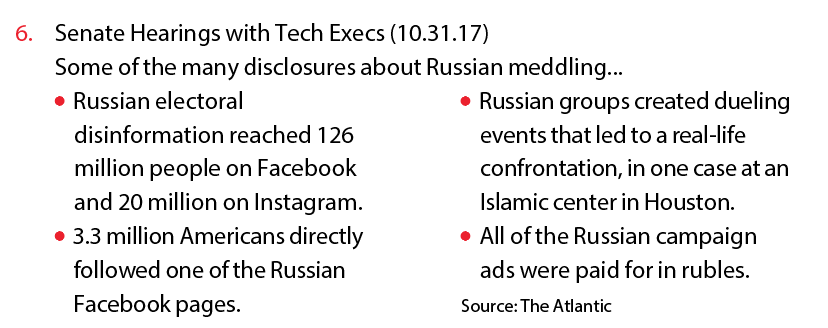

Remember that until Oct. 31, 20176, consumers and politicians believed technology made life better. It had always been that way. And when that stopped, in the early 2000s, it was cleverly disguised, first by Google, then by Facebook, and then by Microsoft and Amazon.

So, we didn’t realize there was harm. We fell in love with the products, but now we’re confronted with the truth. Those products are bad for society and in some cases can be life-threatening. Once you reframe the conversation that way, everybody wants to learn more and almost everyone wants to do something about it.

We are not quite two years into the process of building awareness. Behavior doesn’t change overnight, so I think it’s going pretty well. The best way to solve the problem is to get rid of microtargeted advertising that’s used for manipulative campaigns that are essentially untraceable unless you’re a member of the group receiving them.

How effective are their lobbyists?

Internet platforms are powerful, but growing less so every day. They have all the money in the world. They have large and effective political organizations. But they have an indefensible case to make. And hardly a day passes without a revelation of something truly horrific that they have done.

Recent news of the lawsuit against Facebook related to a breach that resulted in the theft of 29 million identity tokens7, 14 million of which included significant amounts of personal data. Tokens like this would allow the hacker to impersonate people online. Multiple legal cases have been consolidated, so they’re going to move forward. The key element is that Facebook knew about the thefts and protected its own employees, without protecting the people who use the platform. That kind of behavior should not be tolerated.

If something goes wrong in the 2020 elections that can be traced to these platforms, a new conversation has to happen. At that point, the argument shifts from whether we regulate them to whether we should allow them to stay in business.

The internet platforms are not cooperating in trying to protect democracy. At some point the public is entitled to say, “No more.” Elections should matter more than corporate profits. And it will not be hard to replace the platforms with alternatives that aren’t harmful.

DuckDuckGo, for example?

DuckDuckGo makes private versions of search and mobile browsing. If Google search and Chrome went away, DuckDuckGo8 would fill the holes overnight. In markets where there’s no competitor, such as against Facebook, it would not be technically difficult to launch one and scale it up. If Facebook were shut down, that process would take weeks or at most a few months.

Do any public companies pose viable alternatives?

Apple has committed itself to becoming the consumer’s best friend on data privacy. They have a huge advantage over Android and Apple’s new operating system will introduce features that go after the heart of surveillance capitalism.

Apple really takes privacy seriously. They made it part of their business model. That’s a huge deal. If you’re using an Android phone, you’re basically saying you want to make your life transparent to Google. That’s because Android is an extraordinarily well-designed surveillance device.

If you use an iPhone, you’re saying privacy matters to me. Apple’s not perfect, but they are a gazillion times better than Android.

Do you see growing investor or shareholder activism?

When you look at the business of internet platforms, you cannot help but be impressed. The original ideas that underlie Google, Facebook and the advertising-based businesses of Amazon and Microsoft were brilliant. The execution was fantastic.

Investors have rewarded these companies to a degree that’s unprecedented, and it’s completely legitimate given the numbers. During the past year, investors saw the approach of regulators but concluded that regulators have no leverage because users will not permit them to shut down the platforms. To date that’s been a good bet.

At some point I hope investors will begin to question the business practices of internet platforms. Both Google and Facebook are moving into businesses that are much more disruptive to the social order. Google has a smart cities project called Sidewalk Labs, and their project in Toronto may replace democracy with algorithms. Google has made it a condition of the deal that they’d be protected from politics, yet at the same time they want to supervise utilities and other city services.

Do you expect lawmakers and 2020 candidates to intensify their commitment to these issues?

The thing about 2020 that’s so fascinating to me is that in a country where political polarization is extreme, the issue of internet platforms is bipartisan. This issue is about right and wrong, not right and left. No matter their political persuasion, people want an opportunity to understand what’s really going on. And once they have facts they realize this is not political. On one side, you have the million people who work at Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft. On the other side, we have the rest of the country, 329 million people. All agree on this issue.

But for 2020, not all political candidates are equally savvy on these issues. Not many understand that antitrust law is pro-growth, pro-market and pro-competition. If you believe in growth, if you believe in entrepreneurship, antitrust law is a really good thing. In technology, every major cycle was triggered at least in part by an antitrust action. Mainframe computers were made possible by the AT&T consent decree in 1956. Personal computers by the IBM case. Data networking and the internet by Carterphone, which was part of the larger AT&T case. The AT&T breakup accelerated cell phone development and created broadband data communication, which is essentially the internet. And then you created the opportunity for Google with the Microsoft case.

Investors should be cheering for antitrust action. Because in a world with only four monster companies, you won’t get much innovation and eventually they’re not going to optimize for growth. And if they do optimize for growth, they will do it by sucking the profit out of the rest of the economy. That’s what the robber barons did at the beginning of the 20th century, and it’s what these guys are already doing. They’ve sucked all the profits out of the news business, out of the music business. They’re working on video now. Google’s got operations in automotive.

What about the threat to brick-and-mortar retailing?

Amazon is rolling over all of retail, both perishables and non-perishables. They’re doing it in information technology. You have to wonder how long it will be before these guys come after the financial services industry.

Investors should be trying to stop these guys just as a matter of self-preservation. Wall Street has all these great mathematicians, but these guys have great mathematicians and all the data, right? Wall Street is playing chicken with these guys right now. And I don’t want to pretend to know when the bit will slip.

But eventually everybody’s going to wake up and realize, “Wait a minute. It’s not in our interest to let these guys dominate forever.” It’s been really convenient for marketers, right? Marketers love perfect information. The problem is these tech guys are a little bit like banks in 2008. They have perfect information but their customers get spoon-fed the answers these guys want them to have. That’s not capitalism. It’s incredibly destructive.

Investors act in their own self-interest, so I get why they still love these stocks. The time is coming when the right strategy will be to get off the internet platform train and onto a different one. I can’t predict when that’s going to be, but it’s coming. I think everyone needs to pay attention. Consider the case against Facebook over the identity tokens. How are they going to win that?

How is YouTube going to win any case involving children? How is Google Chromebook going to win any case involving children? What they have done is demonstrably harmful. Because they just don’t care. And they keep doing it. The court system is going to be a really active place for this industry over the next few years. Investors should not count on regulators to be as ineffective as they’ve been to this point. In Europe, they are really unhappy about this. When I go to Washington, there are people in both parties who are getting very angry at the way these companies are behaving. Imagine how the Federal Trade Commission feels.

Because Facebook is off the hook for only $5 billion?

They impose a record fine, and Wall Street treats it as “chump change.” They give a blanket immunity and catch a ton of grief for it.

It’s 27 days of revenue for Facebook.

$5 billion9 is a number they will not miss. That’s a problem. These guys are so powerful that you can impose a penalty that’s a large multiple of the all-time previous high and they don’t care. It doesn’t matter because 90 days from now they’ll have earned it back. And the value of the blanket immunity was the better part of a trillion dollars. And from a regulatory point of view, the good news is there’s way more that Facebook has done wrong than just privacy. So there’s a lot of work left to be done.

Hopefully, some aspects of privacy are not covered by the blanket immunity. And people are just starting to look at Google and just starting to look at Amazon.

Would boycotts have any impact?

Boycotts10 aren’t the most effective way to solve the problem. The most effective path is the 2020 election.

Everybody will have an opportunity to engage with politicians. And they should get in their faces and ask, “Why is it legal for companies like Google and Microsoft to scan my email, read my documents and search my messages for data that’s valuable to them?”

Why is that legal for tech companies? Why is it that HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, has so many loopholes that much of our private medical information is available for purchase? Why is it legal for cellular carriers to sell our location? Why can banks, credit card processors and credit rating agencies sell our most intimate financial data? Why is it legal for anyone to track us online? Why is it legal for anyone to gather and hold data about minors?

At the postal service or a telephone company that would be a felony.

These are all real issues and they represent loopholes that these companies have exploited. Too many of us sit there and go, “Well I don’t mind.” Well, hang on just a sec. They have a data voodoo doll, but it’s not because of data you’re putting into their products. The data you put into Facebook, the data you put into Google, that may be one tenth of 1% of what they have about you.

The data voodoo dolls consist of all the data they get from tracking you, all the data they get from spying on your email and perusing your documents, all the data they acquire from banks and healthcare companies, and cellular companies and other applications. All the data they get from surveillance products like Alexa, Google Assistant, Pokemon Go and Sidewalk Labs.

That’s where the data comes from. And you have no control over that third-party data. They use that data voodoo doll for more than targeting ads; they also influence what you see in your news feed, what you get in your search results and the route they choose for you on Google Maps and Waze. Your choices are being influenced, if not made by algorithms. You don’t realize it because you trust these products to be honest brokers when they’re not.

Visit luckboxmagazine.com for the full interview with Roger McNamee.

Big Tech companies combine the data that users willingly provide to create voodoo dolls they can use to manipulate the populace.

7. Last month, a federal appeals court rejected Facebook’s motion to halt a class action lawsuit in which plaintiffs claimed it illegally collected and stored users’ biometric data. Facebook faces potential exposure of billions of dollars in damages.

8. DuckDuckGo

DuckDuckGo, founded in 2008, operates on the premise of privacy, assuring users their search data is protected and isn’t collected or distributed. While DuckDuckGo averages 44 million searches per day, compared to Google’s 3.5 billion, their monthly search averages have been on the rise because of their privacy value proposition.

“We like to say the Internet shouldn’t feel so creepy, and protecting your information should be as easy as closing

the blinds.” —Gabriel Weinberg, CEO