Fakery and the Authentication Economy

Business is booming for companies that identify and combat bogus news stories, doctored videos and counterfeit goods

Fakery permeates life in the 21st century. On every continent but Antarctica, humans and smart machines are laboring around the clock to churn out falsehoods. They’re lying to gain unfair political advantage, peddle bogus merchandise, sabotage competing businesses, manipulate markets or simply to stoke hatred.

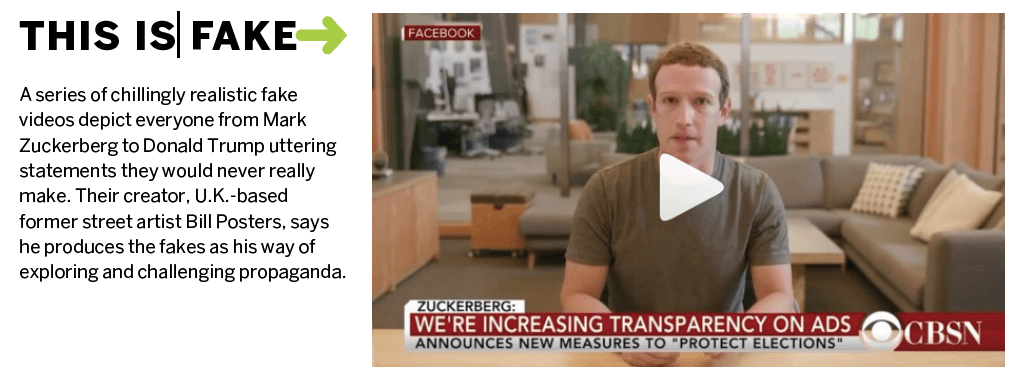

And the onslaught of false narratives is poised to become profoundly worse. Deepfakes—videos that portray incidents that never really happened—are becoming more convincing. (See “The Real Threat of Deepfakes.”) So far, fairly clumsy deepfakes have mostly pasted the faces of celebrities onto the bodies of porn stars, producing bogus porno that doesn’t look real. But soon, as early as sometime this year, deepfakes will almost flawlessly depict politicians delivering statements they would never make. False videos will almost certainly compromise the integrity of the 2020 presidential election and sharpen the already insidious attacks plaguing corporations.

But there’s hope. The avalanche of lies is feeding a booming marketplace for sleuths who sort what’s real from what’s not—call it the Authentication Economy.

Take the example of The RealReal, an online and bricks-and-mortar group of consignment shops that specializes in lightly used luxury-branded merchandise. (See “Getting Real about RealReal,” p. 32.) While most authentication companies use software to reveal falsehoods, The RealReal depends upon a squadron of human experts to verify the provenance of what it sells.

The struggle against fakes began with far-sighted entrepreneurs who established the oldest authentication companies decades ago—long before digital fakery began spiraling out of control. Snopes.com, for example, has been fact-checking and exposing urban legends and hoaxes since 1994.

But it’s not just a matter of checking articles for accuracy. Authentication companies combat the “trending content” model by creating algorithms that assess and rank articles and news sources for accuracy, truthfulness and bias. That holds content creators to account for accuracy.

Companies that specialize in authentication also wage war. They go to battle against bots, the primary distribution engine for online disinformation. The good guys monitor the behavior of site visitors to detect and block non-human behavior. It’s a big job because bots accounted for 52% of internet traffic last year, researchers say.

And the job continues to get bigger. Authentication companies are using something called geometric deep learning, which relies on a new type of algorithm that’s capable of studying huge, complex sets of data. It’s part of the ongoing effort to keep up with the ever-expanding bad behavior that ravages the internet.

Meanwhile, some companies aren’t stopping with authentication. They’ve spent so much time visiting sites all over the political spectrum and authenticating what they find there, that they’re taking the next step and creating content themselves. They’re basing their news stories on the objectivity they hope to have learned by considering as many points of view as possible. (See “Truth be Told,” p. 14.) Such companies are leading a new response to the explosion of online fakery. The technology they’ve designed to detect fakes may also help create a new, truer level of truth.