Truth Be Told: News Is Biased (Odds Are … You Are, Too)

What people say they want in surveys and where they click online doesn’t add up

More than 75% of Americans believe it’s never acceptable for news media to favor one political party over others. Yet big-name media outlets, such as Fox News, MSNBC and CNN, are lambasted daily for alleged favoritism. If media consumers truly prefer neutrality in news, why do they favor biased news platforms?

More than a century before Neil Armstrong would set foot on the moon, English astronomer Sir John Hershel was using a telescope to study it. With powerful new telescopic technology, Hershel purportedly discovered that the moon was home to man-bat hybrid extraterrestrial life.

At least, that’s what defunct New York newspaper The Sun reported in a six-article series in 1835.

The only truthful aspect of the articles, referred to now as the “Great Moon Hoax,” was that Hershel was an astronomer. The telescope was fake, the name of the writer was fake and the journal where Hershel’s research supposedly appeared wasn’t being published at the time. And the man-bats? They were fake, too.

Notably, the moon hoax was published on the heels of what historians call the “Party Press Era,” the period from the 1780s to the 1830s when newspaper editors unabashedly received—and largely depended on—financial support from political parties. In return for the money, prestige and power, editors published endorsements for their parties and didn’t hold back from flinging attacks against the others.

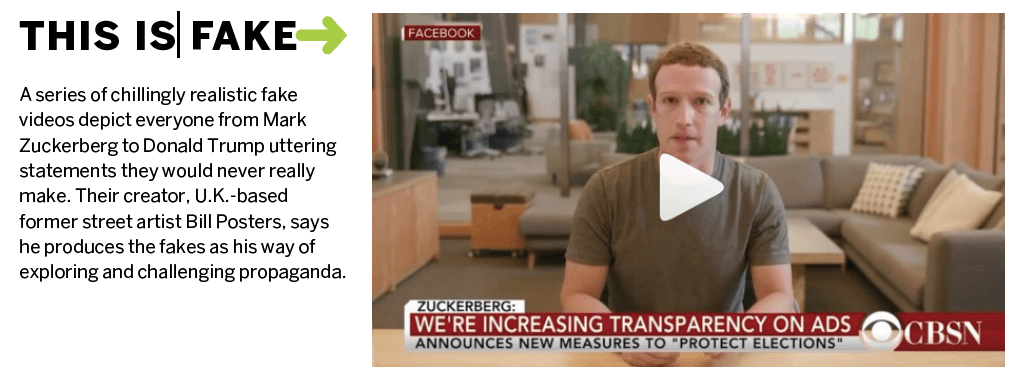

Blatant biases were commonplace, and although the term has only recently been cropping up in dictionaries, nothing’s really new about “fake news.”

Choosing biased sources

Novel or not, bias and disinformation affect public perception of news media today. A 2019 Gallup survey found 28% of Americans had no trust or confidence in the mass media to report the news fully, accurately and fairly. Only 41% indicated that they had either a “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust and confidence, compared with 68% when the survey was first conducted in 1972.

These trends, signaling that trust in news media has taken a beating, beg the question: What, if anything, can be done to restore faith in the fourth estate?

The answer depends partly on truthfulness in media. Americans believe 62% of news in newspapers, TV and radio is biased, according to a Gallup/Knight Foundation survey. And a Pew Research Center survey in 2018 found that 78% of Americans believe it is never acceptable for news media to favor one political party over others when reporting the news.

But what people say they want in surveys and how they vote with dollars—or, clicks—doesn’t neatly match up.

Some news consumers say CNN has an intolerable left-leaning bias and Fox News an insufferable right-leaning one, but SimilarWeb estimates CNN’s landing page racked up nearly 520 million hits in the past six months, and Fox’s scored more than 320 million. During the same period, the pages of outlets with more neutral reputations, such as USA Today and Associated Press News, only saw 119 million and 22 million hits, respectively.

Why then, if consumers can choose sources with more neutral reputations, do they continue to flock to the most polarizing ones?

The underlying causes are a mixture of innate psychological phenomena, including individual biases and tribalism, and technological innovation brought on by the web, such as algorithms. A drive to affirm one’s personal identity plays a significant role, according to Jay Van Bavel, director of the Social Perception and Evaluation Lab at New York University.

“Most citizens cannot tell the difference between a news story and opinion,” Van Bavel told Luckbox. “So what’s happening is they like the opinions that resonate with their own and fit with their own identities and tribal affiliations.”

Reinforcing beliefs

Assessing stories for bias on sites with polarizing reputations, such as Fox News, shows that the news reporting itself isn’t as biased as the opinion-based offerings, according to Van Bavel. “It’s opinion people who are slanted, but the opinion people have the highest ratings because those are the people who appeal to [a consumer’s] identity,” he said.

Algorithms employed by social media sites further complicate matters. More than two-thirds of American adults indicated in a 2018 Pew study that they at least occasionally got their news from social media. Sites such as Twitter rely on algorithms designed to increase engagement to determine what posts users see or don’t see.

Twitter used to put tweets at the top of the feed in chronological order, but that’s no longer the case. Now, Twitter showcases the postings that algorithms judge most likely to reverberate with the user.

Here’s how the changes unfolded: In 2014, Twitter rolled out “recommendations,” which suggested tweets, topics and accounts to follow. In 2016, the platform began restructuring timelines with algorithms favoring “best tweets,” or tweets that garnered a lot of attention. That algorithm was further refined in 2017 to predict and deliver content users would be most likely to find engaging.

That’s good for business but doesn’t necessarily help keep the peace, Van Bavel said.

“Companies make money by having you online as much as possible,” he said, “and to do that they benefit from promoting in your news feeds things that get you worked up the most, either positively or negatively. The algorithms are designed in ways that reward outrage and conflict and polarization. They’re not designed in ways that cool down the temperature of the conversation—that amplify intellectual humility and nuance.”

In a tweet, every word that stirs moral outrage or triggers emotional language causes a 20% increase in the likelihood a user will retweet it, Van Bavel said. It’s a phenomenon that headline writers have learned to embrace.

Near the end of 2018, Twitter introduced the option of toggling between the algorithm-based “Top Tweets” and the chronological “Latest Tweets” models. But the platform assigns anyone unfamiliar with those settings to “Top Tweets” by default.

Persuading social media platforms to abandon algorithmic models that increase traffic, and therefore revenue, is a tough sell. But people could apply psychological approaches to help encourage civil, constructive discourse, Van Bavel suggested.

One of those approaches calls for simply affirming to others that they’re valued before introducing facts contrary to their beliefs or likely to make them uncomfortable, he said. Another is rooted in recognizing one’s own “bias blind spots” before engaging with others.

“It’s starting from a position of a little bit more intellectual humility,” he said, “and so understanding that may make the conversation go better rather than if you come off as somebody who is arrogant and a know-it-all.”

The polarizing web

John Gable, who formerly served as lead product manager for Netscape Navigator, told Luckbox he saw the potential the internet held for political polarization as far back as 23 years ago. After reading Neil Postman’s book Amusing Ourselves to Death, Gabel came to believe that the transition to the internet as a dominant medium, much like the transition from written word to television, could introduce new ways for people to discriminate against each other.

“And that led me to create a patent on how to identify bias,” Gable said. “The idea was to be able to identify different points of view—different sentiment, if you will—so that we could automatically show different points of view and give people a more complete picture.”

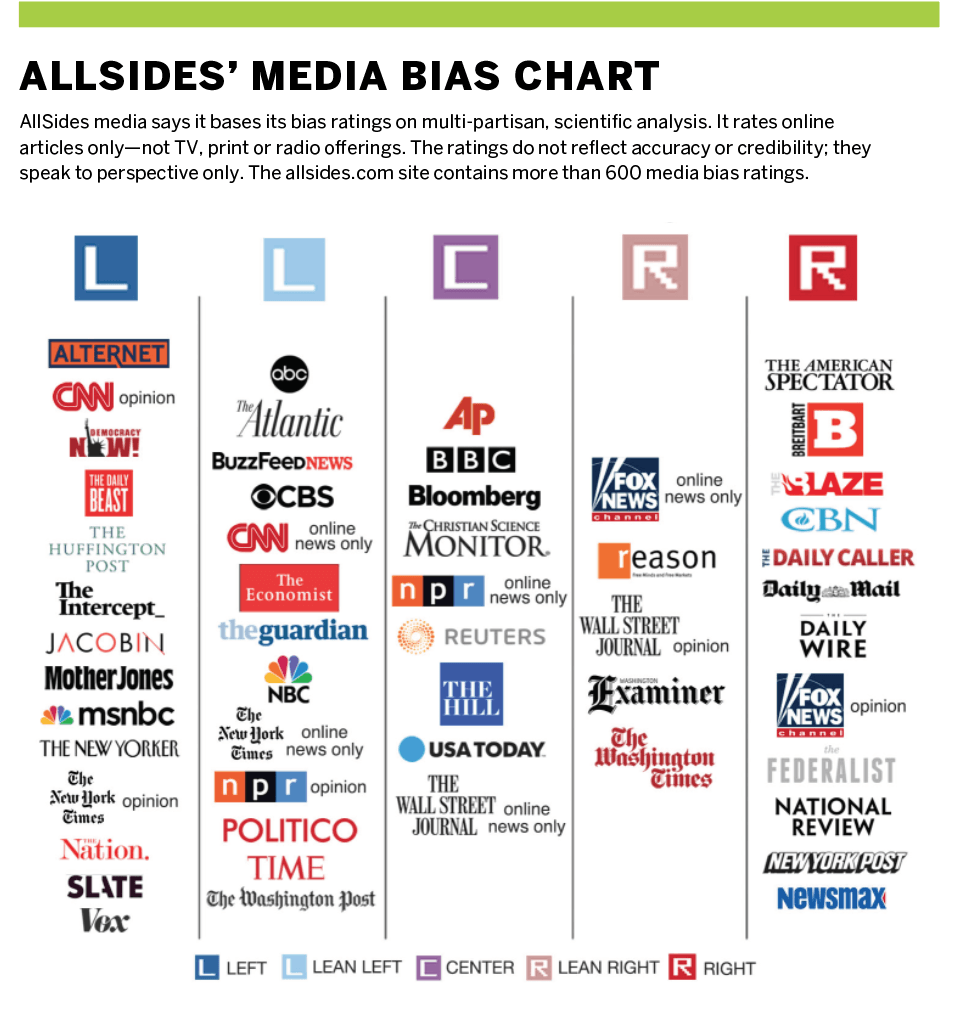

So Gable put together a prototype, and in 2012 launched AllSides, a site that aims to “strengthen our democracy with balanced news, diverse perspectives, and real conversation.”

He built the site upon the notion that unbiased news doesn’t exist—and the belief that that’s not a bad thing. Instead, because social media and search browsers are designed to promote either the most popular opinions or the ones that match consumers’ preferences, it’s important to hear from all sides, breaking people free from “filter bubbles.” Center news often leaves out arguments from the left and or right—arguments sometimes essential to seeing humanity in all its diversity, Gable said.

So AllSides, where Gable serves as CEO, assigns the bias ratings of “Left,” “Lean Left,” “Center,” “Lean Right” and “Right” to help visitors identify the perspectives of their news and explore perspectives they might not have otherwise. The site enables visitors to search for news coverage by specific issues or topics, and in its “Balanced News” section, shows how media outlets with differing bias ratings cover the same story.

“If we were selling food online, and all you’re looking at is clickthrough rates, then the only food we would ever sell are Cheetos and Mountain Dew,” Gable said. “If that’s all you ever eat, you get a stomach ache, and that’s exactly what’s happening with journalism.”

AllSides began as a technology company, and Gable hadn’t intended to create a web destination. Money wasn’t spent on direct marketing, but the press coverage the site attracted brought organic traffic, including visits by teachers who wanted to discuss current events in school but weren’t allowed to because of the perceived biases of news outlets.

“We gave them that ability,” Gable said. “Only two years ago did we start a non-profit for schools, start raising money for non-profit, and we’re already being used in all 50 states by 20,000 students every week.”

“It’s just growing like nuts,” Gable said. The site reaches around three million impressions every month, and direct web traffic increased by at least 20% each month during the second half of last year.

Although detecting fake news and biases in media isn’t as simple today as during the “Party Press Era,” or when “The Great Moon Hoax” made front page news, sites like AllSides are trying to make it easier.

News consumption may have something in common with proactive investing. Without a diversified portfolio, traders run the risk of losing big-time. Without news from across the spectrum, voters could fail to get the whole story.

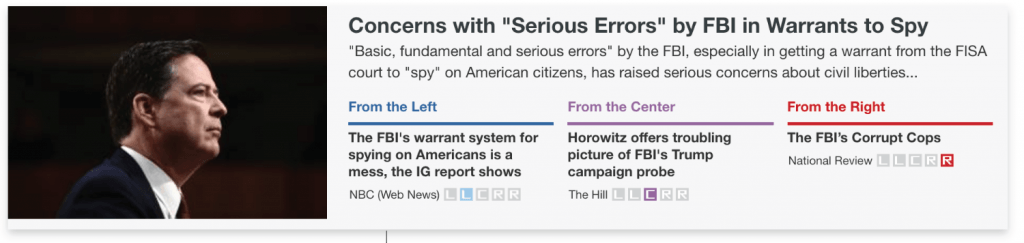

How They Spin It

Media bias assessments from AllSides demonstrate how media outlets serve up varying perspectives on the same event. To illustrate, a recent “headline roundup” from AllSides shows how three publications took perspectives from the left, right and center. After studying a host of articles, AllSides provides its own summation and supposedly neutral analysis of a news event. Here’s what it said about the information it gathered for the headline roundup above:

Concerns with “Serious Errors” by FBI in Warrants to Spy (An AllSides analysis)

“Basic, fundamental and serious errors” by the FBI, especially in getting a warrant from the FISA court to “spy” on American citizens, has raised serious concerns about civil liberties from the left, center and right. Information presented to the FISA (Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act) court was described by Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz as misleading with 17 examples of “significant inaccuracies and omissions” including one case where an FBI lawyer altered an email to help persuade the court to approve a warrant to spy on a Trump campaign aide.

While many groups from the left that normally would be outraged by infringements on civil liberties by national security authorities remained relatively silent, presumably because criticism would politically benefit President Trump, others like the ACLU called for reform. Many on the right were not only outraged by these actions against civil liberties, but also how the FBI under the Obama Administration used misleading and altered evidence to obtain permission to spy on a political rival’s campaign. They felt that even if the Inspector General could not find direct evidence to prove bias, the underlying bias was self-evident and their actions were corrupt.

—AllSides Headline Roundup, Dec. 15, 2019