Activists Poke Amazon’s Shareholders

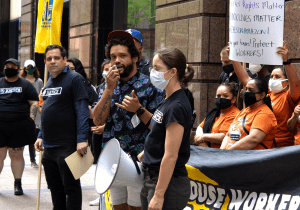

About 30 protesters came together May 25 in front of BlackRock, a financial investment company in Chicago, to encourage Amazon stockholders to vote against what the dissenters view as destructive Amazon business practices.

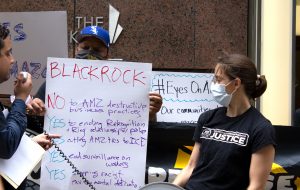

Lining the sidewalk, they waved handmade signs that read “EyesOnAmazon” and chanted “Amazon’s a big polluter, do your part to save our future.”

Their goal was to encourage Amazon investors to vote for the well-being of communities instead of Amazon’s alleged “destructive policies during their next major shareholder meeting,” according to an official of Athena, an anti-Amazon coalition.

The event came after similar demonstrations May 24 in Los Angeles, Boston, Philadelphia, New York and Washington, as part of the Eyes On Amazon Action Alert organized by Athena.

The coalition is attempting to end Amazon’s supposed injustices, which Athena lists on its website as “spying on us, gentrifying our neighborhoods, crushing small business, corrupting politics, polluting the environment and driving its workers to injury.”

Besides the five demonstrations, Athena is asking people to send letters to Amazon shareholders, urging them to “vote against Amazon’s destructive business practices and with our communities at this year’s annual general meeting.”

The events took place before Amazon held its annual meeting with shareholders virtually on May 26, and targeted five corporations that hold 21% of Amazon’s shares: State Street, Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, Vanguard Group and BlackRock.

At the meeting, shareholders voted to elect ten directors to serve until the next Annual Meeting of Shareholders, or until their respective successors are elected and qualified, including Jeffrey P. Bezos, Keith B. Alexander, Jamie S. Gorelick, Daniel P. Huttenlocher, Judith A. McGrath, Indra K. Nooyi, Jonathan J. Rubinstein, Thomas O. Ryder, Patricia Q. Stonesifer and Wendell P. Weeks.

In a statement leading up to the demonstrations, Athena officials said “shareholders have filed resolutions challenging the harmful impacts of Amazon’s business practices on the Black and brown communities.”

Those resolutions demonstrate concern about what coalition members consider Amazon’s use of surveillance in the workplace and the company’s policing communities of color, unfair treatment of workers, and use of surveillance to solidify dominance and market position.

Amazon’s management opposes the proposals shareholders are backing, according to a New York Times article. The company also contends that it aims “to make the company a better corporate citizen, reacting to accusations of labor and environmental abuses.”

Roberto Clark, associate director of Warehouse Workers for Justice, an advocacy group, said it is up to the people to influence Amazon to do more for its employees and the communities it inhabits. Instead of “getting rid of” the company entirely, Clark said the goal is to take a more measured approach. Because the world of online retailing and e-commerce business is not going away, workers should speak out and push the company to do better.

“It is critical to get the word out because public pressure moves Amazon,” Clark said.

In 2020, Amazon brought in more than $21 billion in profit, nearly 84% more than the year before. The company continues to expand, and as demand for its products and services has increased because of the pandemic, working conditions have intensified for independent contractors and warehouse workers making $15 an hour.

Over the last year, organizers and activists have come together to hold Amazon accountable for what they consider its failed pledge to the Black Lives Matter Movement, according to Athena organizers. Activists have fought back against Amazon’s expanding partnerships with police departments, protested the firing of Black whistleblowers who worked at Amazon warehouses and fought Amazon’s environmental damage in Black and brown neighborhoods, which were disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Marcos Ceniceros, an associate director of the Warehouse Workers for Justice, said Amazon has ignored COVID-19 safety precautions and has not responded to pleas for better working conditions. “It’s no secret to most people,” he added.

But the company is not going away anytime soon, Ceniceros acknowledged. “Everyone orders from Amazon,” he said.

In response to the demonstrations, an Amazon spokesperson told Luckbox that “Amazon is committed to the creation of good jobs, a sustainable future, flourishing communities, a strong economy, and successful small and medium-sized businesses. Since 2010, Amazon has invested more than $350 billion in corporate offices, customer fulfillment and cloud infrastructure, wind and solar farms, eco-friendly equipment and machinery, and compensation to our teams.”

At the May 25 event in Chicago, five speakers outlined issues with the company, including pollution, lack of attention to the Black Lives Matter Movement and little support for employees. One of the speakers, Rayshonda Brown, a former Amazon employee, quit her job in one of the company’s warehouses because the company expected her to move heavy boxes while she was pregnant. That led to her pinching a nerve in her neck. But when Brown voiced her concerns to her employer, she said they merely brushed it off.

“Amazon treats you like a slave,” Brown said at the event.

As Clark read a list of the coalition’s demands for Amazon—such as abolishing facial-recognition technology in police departments, cutting ties with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and ending surveillance on workers—employees began to walk out of the BlackRock building, looked at the demonstration and then turned away. The group chanted more loudly.

“We need more action, and we will not give up the fight,” Clark said at the Chicago demonstration.

For more on issues with Amazon, see the interviews with Chris Smalls, Todd Vachon and Danny Caine in the June-July issue of Luckbox magazine.