Is College Worth It?

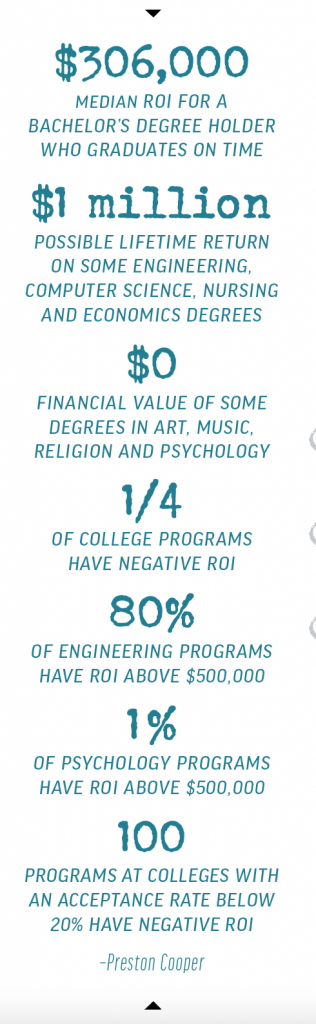

Some degrees increase lifetime earnings by the millions, while others result in a negative return on investment. The biggest factor is your major.

Most young Americans say they want a college degree. But from a financial perspective, choosing a major and an institution can make all the difference. Some programs leave students worse off financially than if they’d never attended, while others can increase lifetime earnings by millions of dollars.

With that in mind, we’ve estimated earnings and lifetime return on investment (ROI) for nearly 30,000 bachelor’s degree programs across the nation and made the information available in an article under my byline at the freopp.org website. Much of the underlying data comes from the U.S. Department of Education and the Census Bureau (see, “The Lesson?” below).

In financial markets, ROI measures profitability relative to cost. For this study, the ROI of a college education is defined as the increase in lifetime earnings a student can expect from that degree, minus the direct and indirect costs of college.

These ROI estimates can help students make better decisions about postsecondary education and also provide direction to anyone interested in higher-education policy.

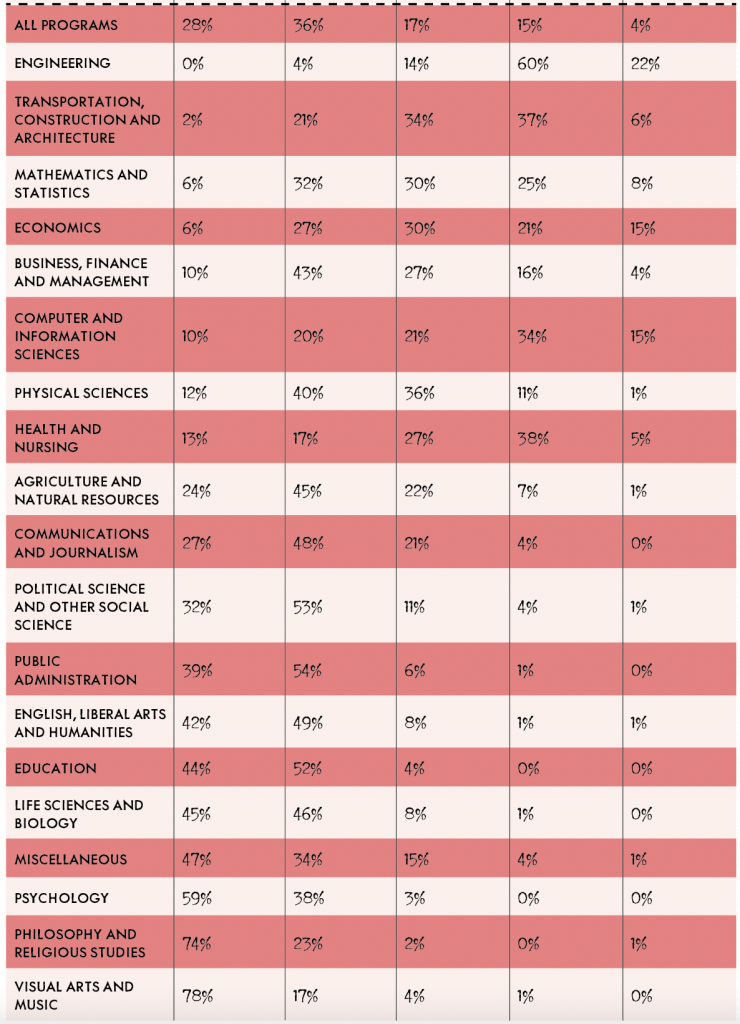

Foremost among the findings is the importance of choosing the right major. College rankings like those in U.S. News and World Report emphasize choice of institution, but research shows the choice of major explains nearly half the variation in ROI.

Students will have a much greater chance of financial success if they study engineering, computer science, nursing or economics—not art, music, religion, psychology or education.

That isn’t to say that lower-earning majors are worthless. Society needs artists and musicians. But low incomes for these majors signal a supply-demand mismatch. Universities are producing too many art majors and too few engineering majors relative to the number of jobs available. As a result, employers bid up the wages of engineers while surplus artists flood the labor market. The answer is not to eliminate low-earning majors nationwide but to reduce their scale.

Attending an elite institution can pay off—but not always. Should you pay more to attend a fancy private school? Sometimes. The best programs in the country are usually at top schools. These colleges and universities may offer more support to boost completion rates, and graduates of elite colleges also have access to professional networks that supply lucrative job opportunities. Pricier tuition can be worth the money if expensive colleges can deliver higher earnings.

But elite schools aren’t necessarily golden keys to success. Even at Ivy League schools, several programs have negative ROI. The choice of major matters more. Engineering and computer science programs at schools without powerful brand names almost always have higher ROI than film or gender studies programs in the Ivy League.

Many bachelor’s degree programs don’t make sense, financially. Having a bachelor’s is usually better than not having one, even if the degree comes with $30,000 of student debt. But after accounting for mediocre completion rates and high costs, many bachelor’s degree programs don’t look too good. Thirty-seven percent of programs do not deliver a financial return when adjusting for spending and completion. Another 32% have a lifetime ROI below $250,000.

Mediocre or nonexistent ROI suggests a misallocation of resources. Many of the students in programs with poor ROI might be better served if those resources were shifted to other forms of postsecondary training, such as apprenticeships, vocational schools or career-oriented associate’s degrees. Because many students do not directly fund most of their own education, policymakers should have a role in a reallocation of funding.

Granted, many bachelor’s degrees have non-financial benefits that students should take into account. Social benefits accrue to some degrees. The engineers who developed the iPhone probably captured only a small fraction of the social value they created. But degrees that generate social benefits often come with gratifying private rewards. Yet, the idea that most negative-ROI programs are generating enough social benefits to justify themselves is doubtful. Degrees with social benefits can also have large private ROI.

Moreover, bachelor’s degrees can generate social costs. As the share of the population with a college degree rises, employers seek stronger educational credentials from job candidates, even though the skills required for those jobs have not changed. It follows that some college graduates simply take jobs away from non-college graduates. This displacement effect likely explains much of the college wage premium. While college graduates benefit, the economy does not grow overall.

For prospective college students, though, those considerations reside largely beyond their immediate decisions. Estimates of ROI should empower students and their families to make more informed decisions. The most important financial question is not whether college is worth it, but how they can make college worth it.

The Lesson? Graduate on Time

When accounting for the risk that a student will drop out of college or take longer than four years to finish, median ROI drops from $306,000 to $129,000. Twenty-eight percent of bachelor’s degree programs have negative ROI when adjusting for the risk of non-completion. If ROI is adjusted to reflect the underlying cost of education, not just tuition charges, the share of non- performing programs rises to 37%.

Preston Cooper, is a senior fellow in higher education policy at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. He is also a contributor to Forbes.com. @prestoncooper93