Existential Threats Aside, AI Will Be Good For Your Health

Algorithms are already surprisingly good at diagnosing ailments, recommending treatment and predicting 10-year heart attack risk. But don’t get too excited.

You shouldn’t expect to have a robot doctor—at least not anytime soon. But artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing health care faster than you might imagine. It’s already creating fresh opportunities to help doctors forecast future ailments and personalize care for individual patients.

The main advantages of using AI in medicine come from its super-human ability to read and analyze gargantuan amounts of data and find patterns humans might not see, even if given years to study the same information. That gives AI the potential to make your doctor more efficient, better informed and more likely to make the right medical decisions.

Studies in the United States and United Kingdom show AI is already surprisingly good at predicting 10-year heart attack risk, diagnosing ailments and recommending treatment options to address them.

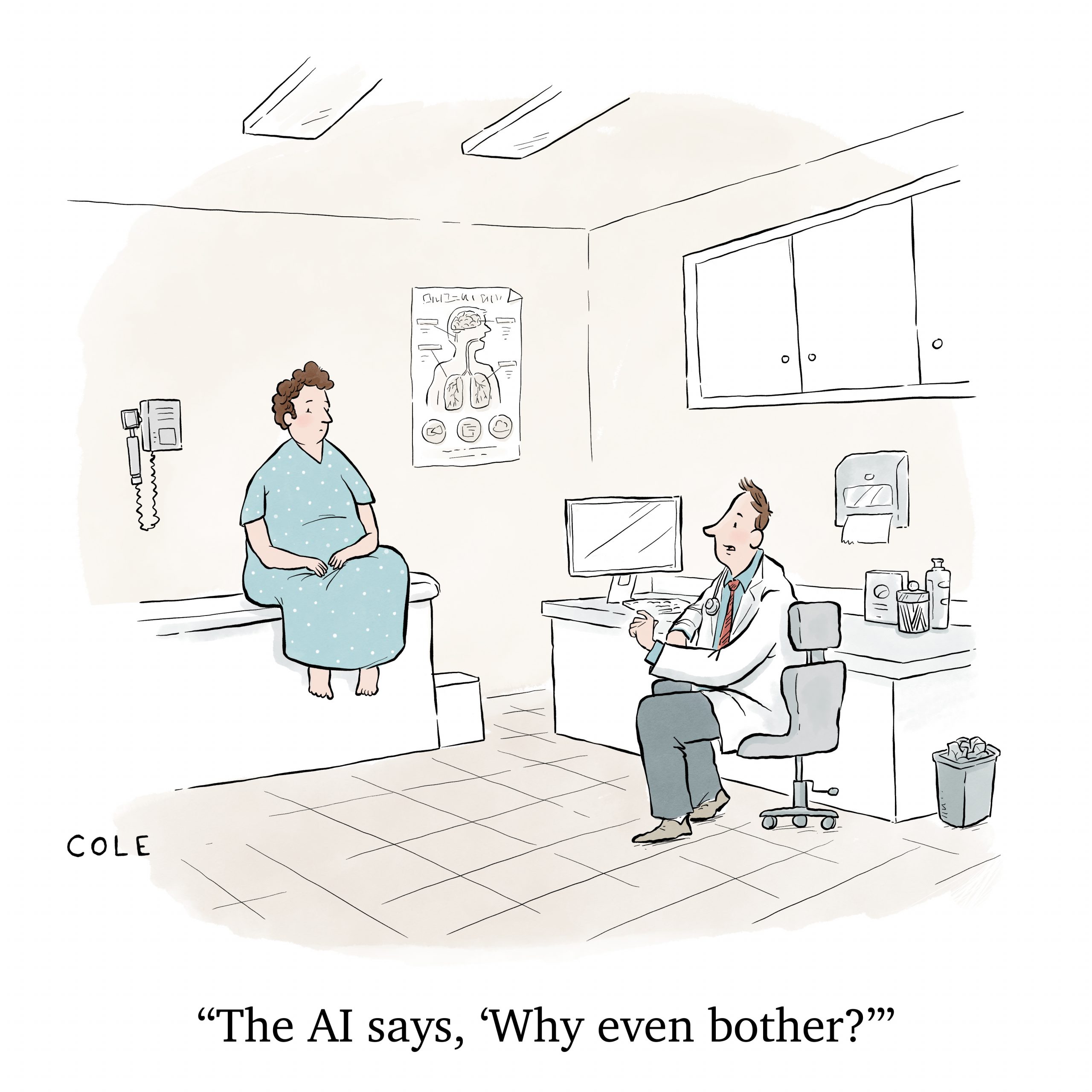

But don’t get too excited just yet. AI still lacks the intuition and self-awareness of a human doctor. And all the rapid calculations performed by AI algorithms can produce mistakes and electronic “hallucinations” that don’t make sense. Plus, issues of cultural and racial bias and medical privacy raise important concerns.

Limitations aside, AI’s number-crunching and pattern-recognition prowess opens the door to making algorithms among the most important gadgets in the medical bag, along with stethoscopes and pulse oximeters. And this not far-off, science-fiction-level speculation. If they haven’t already, patients can expect to start seeing the impact at the exam-room level soon.

Predicting heart attacks

Suppose you had chest pain. Your doctor could respond by ordering imaging tests and find an obvious problem. But not all heart problems are obvious.

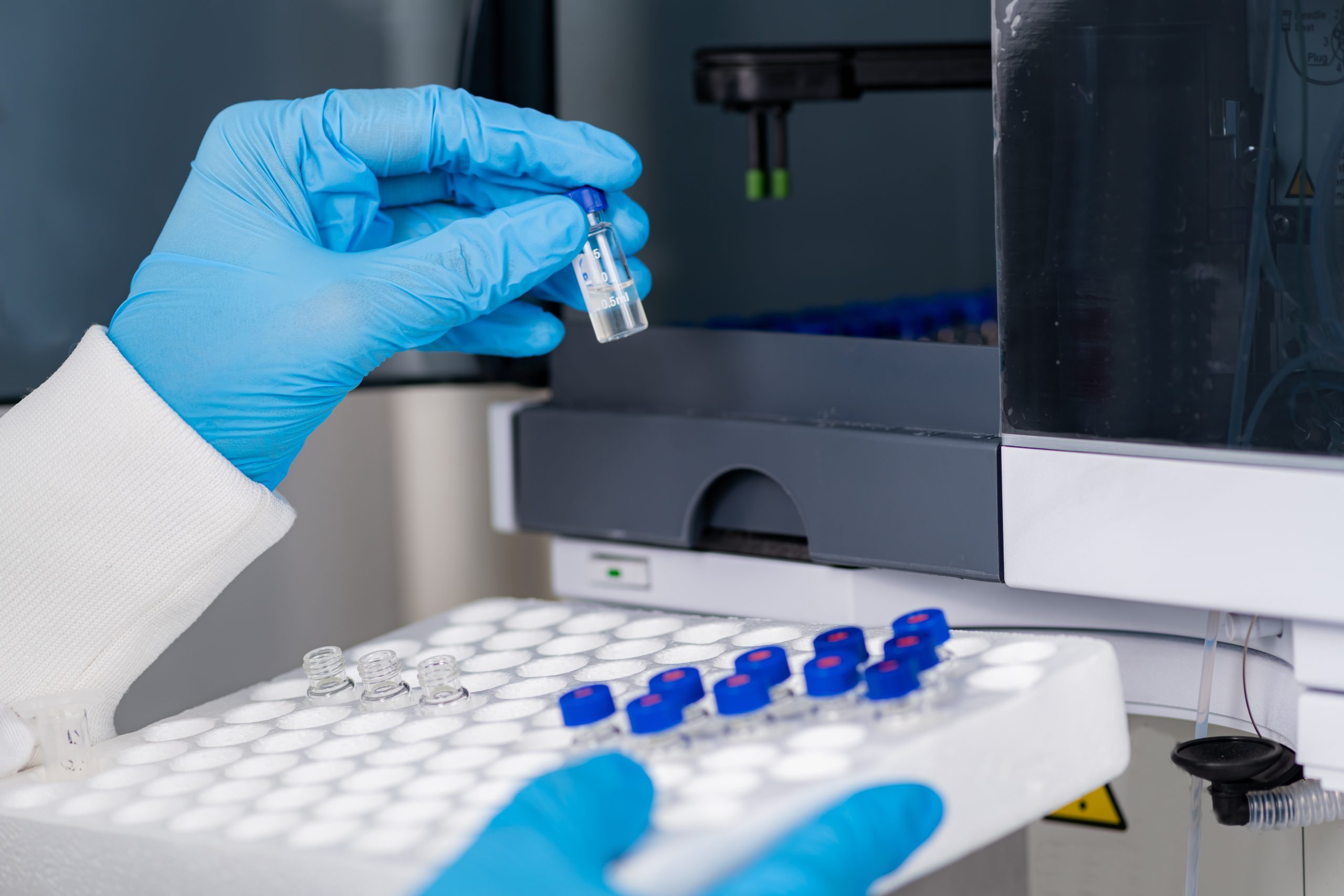

Symptoms that could kill you in 10 years—including some that might be addressed if you changed your lifestyle now—can be hard to spot. But AI technology developed at University of Oxford in the United Kingdom can help clinicians look deeper.

The AI identifies problems not visible to the human eye and, if implemented across the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS), could lead to 20% or more fewer heart attacks and 8% fewer cardiac deaths compared with traditional treatment methods, the Oxford team says.

Caristo Diagnostics—an Oxford-connected tech spinout company—incorporated the technology into a “cloud-based medical device,” called CaRi-Heart. Put simply, the technology combines information extracted from a CCTA scan and other risk factors—like diabetes, high cholesterol, smoking and hypertension—to calculate a patient’s risk of having a fatal cardiac event over the coming decade. It’s already in clinical use in the U.K., Australia, Germany, France and other European Union countries.

The CaRi-Heart technology proved its worth quickly when put to the test, according to an email response to Luckbox from Dr. Charalambos Antoniades, who led the Oxford study and serves Caristo as a co-founder and chief scientific officer.

“Introducing it into the first five hospitals in the British NHS resulted in change of management in 39%-45% of the patients, suggesting that without this technology, we treat inappropriately nearly half of our patients undergoing CCTA,” Antoniades says.

Caristo expects CaRi-Heart to receive United States Food and Drug Administration clearance by the end of 2024 or early 2025 at the latest and in clinical use here soon after that, he notes.

Besides his work at Caristo, Antoniades is chair of cardiovascular medicine at the British Heart Foundation and director of University of Oxford’s Acute Multidisciplinary Imaging and Interventional Centre.

Scientists at the University of Edinburgh developed an AI tool that can diagnose—and rule out—heart attacks with astonishing accuracy. Compared to current testing methods, the algorithm, CoDE-ACS, could rule out a heart attack in more than double the number of patients, with 99.6% accuracy. The university says the technology could greatly reduce hospital admissions.

Assessing ChatGPT

In the United States, research shows that ChatGPT—an AI model that has already shown it can pass medical licensing board and bar exams—can be trained to diagnose patients with as much reliably as an inexperienced doctor.

ChatGPT’s accuracy rate at diagnosing health problems was almost 72% across 36 “clinical vignettes,” or instructive scenarios, according to a study published in May by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital. Its rate was nearly as good as that of a typical recent medical graduate. Another study found ChatGPT an impressive 98.4% accurate at making appropriate breast cancer screening recommendations.

Arya Rao, one of the authors for each of the two studies, says the results show the information-crunching ability of large-language AI models gives them potential as valuable diagnostic tools.

“By myself, I’m not going to be able to read through every single patient file at Massachusetts General Hospital, not just because of [the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act], but because that’s an inhumane level of effort and time that just no one has,” Rao told Luckbox.

Rao, who has a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry and computer science from Columbia University is a student in the MD/PhD program run jointly by Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Junk (or bias) in, junk out

The problem with using AI in medicine is that the algorithms can become out of date or can include cultural or ethnic biases that lead them to the wrong conclusions.

Algorithms can fall victim to their own ability to learn and establish correlations between incoming patient data and patient outcomes, a study in October by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the University of Michigan found.

The study indicated that using the AI models to adjust treatment can, in turn, alter the baseline assumptions used to train the models. The result, researchers found, is that the performance of such models can degrade over time.

Predictive AI models need regular maintenance to keep them running at peak efficiency, said a co-author of the study, Dr. Girish Nadkarni, director of the Charles Bronfman Institute for Personalized Medicine at Mount Sinai Health System.

“The hypothesis is that if you can figure out what will happen to a patient well in advance, you will take steps to change it and you will change the outcome, so a bad outcome gets converted to a good one,” Nadkarni told Luckbox. “And instead of dying, the patient survives, which is a great outcome for the patient.”

But that process introduces data issues, he noted. AI models must be retrained on a regular basis because of changes in practice patterns, patient populations and hospital systems.

Nadkarni described AI as “a tool in your toolkit” that should be regularly sharpened. “And if you don’t maintain it and if you just let it run without proper oversight, proper governance and proper maintenance,” he said, “then that is not going to be the best thing for anyone.”

Another problem he has observed is that bias can creep into AI models and unintentionally put minority communities at a disadvantage.

The danger of bias and misuse

None of AI’s potential problems and opportunities are reasons to either avoid using AI in health care, or rely on it without caution, said Nadkarni, who is also a medical professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

He said the world seems divided into those who fear the advent of Skynet—the fictional evil artificial general superintelligence system depicted in the Terminator movies—and those who think the technology will be unequivocally safe and beneficial.

“I think both these groups of people are missing the point,” Nadkarni said.

“It’s going to be a great tool,” he said, “but we are missing the short-term dangers that are right in front of us without worrying about Skynet. We’re seeing things like biased decision making, both by physicians, patients and health care entities, because of biased data and biased algorithms. We are missing misinformation that can now be weaponized and almost industrialized.”

The alleged misuse of predictive algorithms is at the core of a class-action lawsuit filed against UnitedHealth Group (UNH) in Minnesota on behalf of two deceased UnitedHealthcare Medicare Advantage beneficiaries.

It’s claimed in the lawsuit that the health insurer used an AI model called nH Predict, to set “rigid and unrealistic predictions for recovery” of Medicare Advantage-enrolled patients in post-acute-care rehabilitation facilities.

UnitedHealth staffers used the platform “to wrongfully deny elderly patients care owed to them under Medicare Advantage Plans by overriding their treating physicians’ determinations as to medically necessary care,” the Plaintiffs said in the lawsuit. They also claim the AI model has a 90% error rate.

Time for regulation?

“Obviously, industry collaboration is critical,” Nadkarni said. “And I’ve started companies myself. But at the same time, the incentives have to align in order to make sure that it’s good for the commonwealth.”

He said the government needs to step in to make sure AI algorithms aren’t used by health insurers and others to discriminate against patients or use their data in other ways that could hurt them.

“There needs to be regulation around that soon,” Nadkarni said. “Now there’s precedent for this with the [The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008] GINA … no one can discriminate against you based upon your genetic mutations.” He said the U.S. needs a similar law dealing with AI algorithms.

President Joe Biden signed an executive order on Oct. 30 to seek to address privacy and safety issues related to AI, including AI-facilitated misuse of private medical information.

Nadkarni praised the order but worries that it doesn’t provide enough protection and lacks the authority that a law passed by Congress would convey.