Getting Real About The RealReal

A consignment marketplace detects fake merchandise, but is its stock price for real?

The RealReal (REAL) has been pioneering the authentication economy for nearly a decade. The company employs a squadron of experts to ensure fakes don’t enter the product mix of designer labels in its luxury consignment marketplace.

Its customers are buying secondhand clothes, jewelry, watches and home furnishings, but they demand lightly used merchandise of high quality. To ensure they get it, The RealReal relies on specialists in disciplines as esoteric-sounding as horology (watches) and gemology (gems).

The RealReal operates online and has been building physical stores.

In 2018, the company facilitated 1.6 million transactions worth

$710 million for more than 400,000 different buyers.

Customers value the service. Buying and selling secondhand luxury goods online presents a challenge because of the proliferation of knockoffs. If, for instance, someone posts a Gucci handbag for sale on eBay (EBAY), it’s difficult—if not impossible—for potential buyers to verify its authenticity. As a result, buyers don’t want to pay full price. So no one wants to sell authentic goods on the platform. This creates a negative feedback loop that ensures most of the luxury goods offered online are fake.

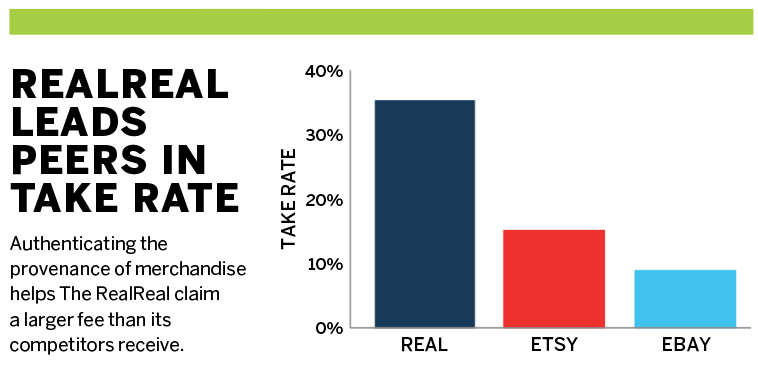

The RealReal addresses this problem by authenticating merchandise and handling all elements of the sales process, including photography, pricing, fulfillment and returns. Such extensive services enable the company to retain a significant portion of the money buyers spend. The take rate, the percentage of each order it keeps as a percent of revenue, was 36% in 2018. eBay’s take rate was just 9%, and craft goods marketplace Etsy’s (ETSY) take rate was 15%, as shown in the chart below.

The company’s consignment empire has been growing, but its stock price of $17 per share at press time tells a different story. The company had its initial public offering June 28 of last year at $20 per share. The stock reached a high of $28 on its first day of trading before steadily declining during the next two months to a low of $13 per share on Aug. 27. From there, the stock rebounded to $24 per share by the end of October before crashing again to $16 per share on Nov. 21.

That wild volatility reflects the key underlying question for The RealReal. Does it have an innovative new business model that has found a profitable niche? Or is the company, whose CEO previously ran

Pets.com, destined to crash and burn in the same way?

While The RealReal keeps a larger portion of the money spent on its site than its peers, it also spends more to earn that revenue. It pays the cost of authenticating, merchandising, shipping and accepting returns for all the items it sells.

What’s more, many of those costs are not reported in cost of goods sold. Instead, they are reported as “operations and technology” expenses. According to the company’s S-1 filing: “Operations and technology expense principally includes personnel-related costs for employees involved with the authentication, merchandising and fulfillment of goods sold through our online marketplace, as well as our general information technology expense.”

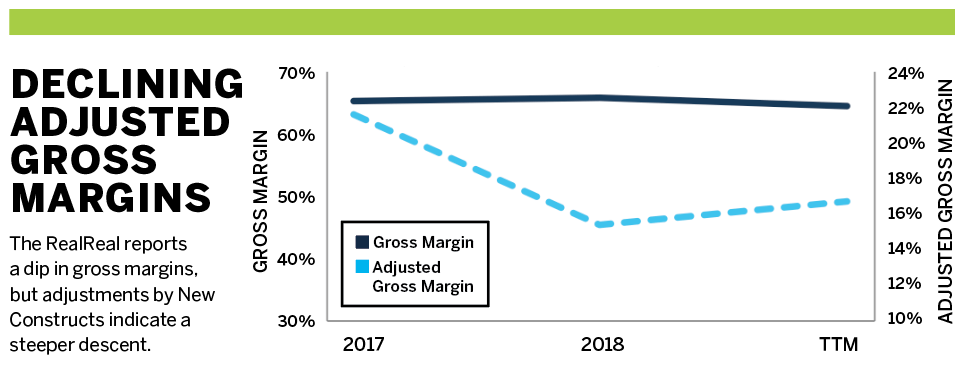

Much of that cost relates directly to the delivery of The RealReal service and should be included in cost of revenue. By reporting those costs separately, the company makes its gross margin look higher and presents a potentially misleading picture of its path to profitability.

The chart on page 26 shows that The RealReal’s gross margin has remained consistent at ~65% since 2017. However, if operations and technology expense are included as part of the cost of revenue, its “adjusted gross margin” declined from 22% in 2017 to 17% over the trailing 12 months.

The RealReal says that it expects operations and technology expenses to decrease as a percentage of revenue over the longer term. That chart also shows they’ve made progress on that front over the trailing 12 months, but they remain a long way away from getting back to even the 2017 margin, much less the level they need to be to achieve profitability.

Overall, the company’s net operating profit after tax (NOPAT) decreased from -$47 million in 2017 to -$66 million in 2018, but its NOPAT margin improved slightly from -35% to -32% at the same time.

The RealReal seems like it should have a profitable business model. It fills an underserved niche and has relatively little direct competition. However, the company has yet to show significant concrete progress toward achieving profitability.

It’s possible that it’s in a business that’s simply not profitable, which would explain why very little competition has emerged.

A beneficial recession?

While luxury goods manufacturers struggle during economic downturns, The RealReal’s consignment business could actually benefit from poor economic conditions. Shoppers who normally buy new luxury goods might substitute used merchandise during a recession. The company could also get a large influx of sellers needing extra cash.

It’s also possible that the decline in spending on luxury goods during a recession would more than offset the substitution effect and become a net negative for the company. As with other recent IPOs, the markets have never seen this company operate during a downturn and thus have no idea how it will perform.

Still, investors have reason to hope this company is well-equipped to handle a recession.

High expectations

Analysis of the cash flow expectations baked into the current stock price reveals the stock price is high. To justify the current valuation of $17 per share, the company must achieve 12% NOPAT margins (comparable to Etsy) and grow revenue by 25% compounded annually for the next seven years.

If The RealReal can grow revenue at the same rate but achieve NOPAT margins of 19% (equal to eBay), the stock is worth $29 per share today, an 80% upside to the current stock price.

A 25% compound annual growth rate seems achievable for a company that grew revenue by 52% year-over-year through the first nine months of 2019, so the issue is margins. Given the high take rate, the company should be able to achieve comparable margins to its peers (with some cost controls), in which case the stock is undervalued. However, the poor performance of the stock since its IPO shows that investors are not satisfied with promises and want to see progress toward profitability right now.

Too often, investors bid stocks up on the hope the company will be the next FAANG (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google) stock. “Hope” isn’t a good investment strategy. The FAANG stocks are driven by once-in-a-decade or even once-in-a-generation disruptive technologies.

Given that the current NOPAT Margin is -32% and the current valuation implies the company will achieve 12% margins, while also growing revenue by 25% compounded annually for seven years, the best case scenario (or something close to it) is fully priced into the stock.

New Constructs rates the stock Unattractive. At the current price of $17 per share, investors should sell. The risk/reward looks poor. The stock price reflects a best-case-scenario future, while the business is not close to achieving that future. Too much upside is priced into the current valuation while too much remains because of negative margins.

Until the company makes more progress and proves it can achieve margins comparable to its peers, investors should take profits in The RealReal and wait until the company shows it can exceed the already high future cash flow expectations baked into the stock price.

The Fakery of Consensus Earnings

The earnings recession isn’t news. But what most investors don’t know is that core earnings, when adjusted for unusual gains or losses hidden in footnotes, are a lot worse than investors and markets realize. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 has been on a tear this year, up nearly 25% and currently at an all-time high.Those two seemingly inconsistent trends give rise to a question. How do stocks rise when the underlying fundamentals fall? Answer: Most investors aren’t aware of the severe decline in core earnings because they don’t read the footnotes.

Over the trailing 12 months, GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) earnings fell 1% while adjusted core earnings fell 6%. Most investors know GAAP earnings are prone to distortion because they include lots of non-recurring or unusual factors. Most investors aren’t aware that the core earnings (from CompuStat or Wall Street analysts) are also distorted by unusual factors.

In fact, earnings for the S&P 500 were distorted by 22% on average in 2018, according to New Constructs, an equity research firm that adjusts data with the aid of machine learning. Earnings distortion from hidden gains is rising rapidly, and core earnings from traditional sources have not been overstated this much since 2000. The rapid rise in earnings distortion since 2015 means that an increasing amount of corporate income is coming from unusual or one-time gains, which is not apparent to investors analyzing press releases or income statements. Corporate managers hide the one-time nature of these gains by disclosing them only in the fine print. In other words, managers are dressing up the numbers in an increasingly aggressive manner over the last few years.

David Trainer is CEO of New Constructs, an independent equity research firm that uses machine learning and natural language processing to parse corporate filings and model economic earnings. Sam McBride is an investment analyst at New Constructs. @newconstructs