Managing the Menace of Internet Powerhouses

A diverse panel plumbs the excesses of Google, Amazon and Facebook

The ravenous rulers of the internet aren’t satiated by the tasty data that innocent users willingly feed them. They augment that information with the voluminous intelligence bought and sold by financial institutions, healthcare providers, location trackers and just about any other imaginable entity that operates online. Eventually, the internet platforms know people better than people know themselves. They can reliably predict behavior and manipulate it for profit. They’re using data to invade privacy, seize monopolistic control, purvey false narratives and threaten the very existence of democracy in America. In this roundtable, six tech experts bring to bear their talents as authors, attorneys, investors, activists, thinkers and administrators in response to 10 questions from luckbox. The panelists clashed on details and even on fundamentals, but all agreed on the desperate need for action. —Ed McKinley

luckbox: How well are regulators overseeing privacy and user data practices at Google, Amazon and Facebook?

Jonathan Taplin: Two years ago, nobody on the policy side was even looking at these issues from a regulatory standpoint. That’s changed a lot, with the FTC [Federal Trade Commission] fining Facebook $5 billion and with the European Regulatory Commission fining Google

$3 billion. I don’t necessarily think they’re going in all the right directions, but at least it’s a start.

Jeremy Carl: I’d give them D or D minus. I’m not giving it an F because regulators finally seem to be waking up. But the privacy violations by Google and Facebook are mostly being greeted by a slap on the wrist.

Chris Lewis: Washington gets a D+ for its efforts over the past few years. We have no privacy rules in the United States that govern consumer privacy protection online. Instead, we have a regime close to industry self-regulation.

Matt Stoller: Big tech platforms regulate our democracies right now, not the other way around. The efforts of policymakers and enforcers are largely pathetic and embarrassing—or downright corrupt.

Daniel Crane: I’d disagree. The Federal Trade Commission has made efforts to enforce user privacy and data standards and is to be commended for not trying to roll out anything as heavy-handed as the European Commission’s General Data Protection Regulation, which creates a monstrously complex regulatory scheme that makes it difficult for small- and medium-sized companies and individual proprietors to maintain business databases.

Cindy Cohn: Dan’s partly right. In general, oversight by the FTC has been a good effort, given how their hands are tied. But the current limits of their power and budget, along with the FTC’s fear of Congress stepping in and cutting them back, leaves much to be desired. The public deserves more. The oversight that the FTC can give is not keeping up with the privacy needs of the public. We need all three branches of government working to protect our privacy.

Should lawmakers revisit the “safe harbor” offered internet platforms under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act?

Taplin: The safe harbor regulations should be revisited. Essentially, companies like Facebook, Google and YouTube have no liability. It lets these people be totally reckless. They want more posts and more content because that gives them more users. If they had actual liability for what happens on their servers, then they’d be a lot more careful about allowing people to post mass-shooting videos, ISIS beheadings or any of the other horrible things that have been on YouTube or Facebook.

Carl: Safe harbor absolutely has to be on the table. It’s the one true piece of leverage we have over Big Tech. It’s the one thing they really fear. During the original debates over Section 230 in the 1990s, the tech companies promised they would offer “dumb platforms.” In exchange, they were granted special liability protections far in excess of what was offered to offline companies. They built multi-billion dollar businesses off of those special protections and then turned around and started making politically biased editorial decisions on what was allowed on their platforms—in direct violation of their original promises. It’s unconscionable.

Lewis: On the contrary, Section 230 is a foundational law for the internet, and we need it. Its liability protection makes it possible to have user-generated content without significant content moderation. Without its basic protections, liability risk could lead to either extreme moderation that limits user speech, or virtually no moderation, resulting in online communities most users wouldn’t want to visit and would likely silence marginalized voices. But it’s not the final word in internet policy. Policymakers can address concerns about online harms with targeted laws that set expectations for digital platforms with respect to user-generated content that do not detract from Section 230’s core purpose of facilitating speech and permitting different platforms to adopt diverse moderation policies.

Stoller: That safe harbor was largely designed for neutral communications networks, to allow companies to have forums where they enabled the speech of others without having to take responsibility for what those speakers said. Advertising is the distortion of the flow of information. Facebook sold roughly $50 billion in ads last year, which means it made large amounts of money by distorting what its users see and read. If the company is going to curate and edit content so it can make ad money, it shouldn’t be legally immune from passing along content that is harmful or illegal.

Crane: Maintaining some version of the safe harbor is essential lest a “heckler’s veto” jeopardize freedom on the internet. If internet providers become liable for all of the abuses committed by users on their platforms, they will respond by censoring large swaths of user content based on overbroadly keyword searches or similar technologies. In such a system, a few maliciously intentioned people could spoil internet freedom for everyone else—the heckler’s veto.

Cohn: First of all, Section 230 is not a “safe harbor,” so I’m worried that the premise of this question is not correct. This isn’t just semantics. A safe harbor is something conditional that you get only if you do certain things. Section 230 simply says that if you aren’t the speaker, you cannot be held liable as if you are. There has been a concerted effort—some of it honest and some of it dishonest—to convince lawmakers and the public that Section 230 is the answer to the problems with Big Tech. I think this is deeply misguided. Worse, I think that it will backfire and further harm already marginalized speakers.

Are you concerned that curbing Big Tech may limit free speech?

Carl: I’m more concerned about exactly the opposite—Big Tech running amok is what is damaging free speech. Viewpoints that are not popular with tech overlords—and the young 20 and 30 something “woke” programmers who work for them—are being arbitrarily and capriciously barred from these platforms. Similarly, their decisions about what is and isn’t “fake news” are similarly politically biased.

Stoller: The threat to free speech is coming from tech platforms that have centralized global communications in a way that is unimaginably powerful. There are ways to make the problem worse, but without action we are in deep trouble.

Crane: That depends on what kind of curbs we’re talking about. There is no “curbing Big Tech” without “using bigger government.” An expansive regulatory system ostensibly designed to “protect the internet” would end up imposing the views of government bureaucrats on everyone else. A system dominated by a few Big Tech companies isn’t perfect, but it’s better than a system dominated by one big government.

Cohn: There are many non-censorship paths to curbing Big Tech, including creating real competition through both law and policy, as well as through technical means, like encouraging adversarial interoperability. Curbing big tech without limiting the free speech of the rest of us is both possible as well as critically important right now.

The FTC’s recent $5 billion settlement with Facebook over the Cambridge Analytica privacy abuses is the largest in history but also the equivalent of one month of revenue for the company. A good start, or a lost opportunity?

Stoller: It’s a corrupt joke. Facebook offered a $5 billion payment on the condition that the FTC not finish the investigation. The agency did not interview Mark Zuckerberg, nor did it get access to his files. This was a bribe to a regulator looking for a good headline.

Crane: To the contrary, it was a good start. The $5 billion fine may not have been a damaging blow to Facebook, but it’s still a lot of money. And the bigger repercussion to Facebook was reputational. But, look, if people don’t want to use Facebook, they don’t have to. I don’t. If people think Facebook is doing a terrible job protecting their data, they can walk away. There are a lot of other ways to reach people on the internet. If people choose to stay, even in light of scandals like Cambridge Analytica, they are doing so with their eyes open. You may feel differently about your data and Facebook’s promises, so act on your own feelings. It’s a free country!

Cohn: It’s a lost opportunity but not really the FTC’s fault. The FTC has limited power and doesn’t want Congress to intervene.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren wants to categorize large tech companies as “platform utilities” and regulate them that way. She also wants to break them apart by rolling back what she views as recent “anti-competitive tech mergers.” Feasible?

Crane: In American history, only two companies—Standard Oil and AT&T—have been broken up on antitrust grounds. It’s not something the courts have generally been willing to do, and mostly for good reasons. Apart from recent mergers, where divestitures of recently acquired assets are a viable remedy, ripping apart long-standing companies is generally bad for consumers, shareholders, employees and society at large. As for making the big tech companies “platform utilities,” that style of command-and-control regulation by public utility commissions has been tried and long since abandoned. Competition is a much better driver of outcomes than heavy-handed regulations.

Carl: I don’t agree with Sen. Warren on many things, but I think they are viable proposals and need to be on the table. In particular, Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp need far more scrutiny. I’m not at the point that I’d say breakup is my preferred remedy, but if we can’t solve their monopolistic abuses any other way then it’s something we’d need to look at. These big tech companies are in fact platform utilities and need to be regulated accordingly. And if you look at the innovation that occurred in the telecom marketplace after the breakup of Ma Bell, it’s hard to argue that a breakup would be inherently destructive.

Stoller: Sen. Warren’s proposals are quite moderate. We have a long history of breaking up companies in the United States, and it pretty much always delivers positive benefits to everyone.

Is there bipartisan political will to address the anti-competitive practices of Google, Amazon and Facebook?

Taplin: That’s not the problem anymore. The astonishing thing is that it’s not a left-right issue anymore. If senators Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Elizabeth Warren can agree that these companies have gotten too big and are exercising too much power, then it’s not a political discussion.

Carl: There’s an opportunity for unusual left-right cooperation because there’s bipartisan voter concern about the abuses of monopoly power by Google, Facebook and Twitter. Politicians on the right from President Trump to Sen. Ted Cruz to Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) have shown significant concern. Politicians on the left, including presidential candidates from Sen. Elizabeth Warren to Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-Hawaii), want to take on big tech’s power. My concern is that some of those on the left would prefer solutions that involve even more censorship of Americans’ views online—often in the name of curbing “hate speech.” Any solution to Big Tech problems has to protect First Amendment freedoms.

Lewis: The will for bipartisan action is not quite there yet. Unfortunately, there is more heat than light around the facts of the digital platform market. Unproven claims of ideological bias distract from the need for bipartisan action to promote content moderation and pro-competition rules for dominant platforms.

Stoller: But, increasingly, the will is coalescing.

Crane: There is certainly a level of political interest in antitrust that there hasn’t been since the 1950s. And, yes, it’s coming from both sides of the political aisle. The heightened political pressure in Washington has already changed the practical reality for these companies. Acquiring nascent competitors is already much more challenging. But will there be political consensus in Washington to pass a big new antitrust statute? We haven’t done that since 1950, and I doubt it’s in the cards today.

Cohn: I don’t think the bipartisan will is there. A lot of people hate these companies on both sides of the aisle. But the reasons they hate Big Tech are so different and contradictory that it’s hard to see a shared coherent policy response aimed at creating competition coming out of the current debate.

Why aren’t Big Tech data privacy issues resonating with the general public?

Taplin: The problem is these platforms have become so much a part of life. How could you operate without Google? It’s the old T-I-N-A—there is no alternative. That’s exactly what the word “monopoly” means. Google is critical to most people’s work existence and probably to their social existence. And Amazon has become that for a lot of people.

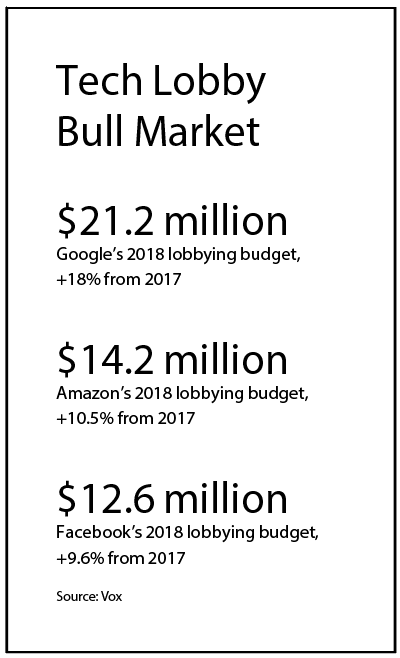

Carl: First of all, we’re in a much better position than we were a few years ago in terms of public awareness and concern. With each scandal, voters are showing more concern. Unfortunately, we also have a lot of politicians on both sides of the aisle who have frankly been bought and paid for by Big Tech. Google is the top corporate spender on lobbying in the country—so much for “don’t be evil”—and Facebook and Amazon aren’t far behind. They’ve done an equally good job of paying off significant think tanks and media. And a lot of my colleagues on the right have fallen into this sort of naïve “free market” defense of Big Tech that ignores the issue of monopoly power. In reality, there’s nothing “free market” about granting special legal privileges to monopolies and then letting them run amok.

Lewis: The public isn’t ambivalent, it simply isn’t empowered or informed about solutions. This is why careful analysis by policymakers like the House Judiciary Committee’s hearing series on the digital marketplace, is important in making the public aware of the facts and possible solutions. These services are popular with the public and so their concerns must be matched by careful policymaking that rebalances the power of dominant platforms without destroying the benefits the public loves.

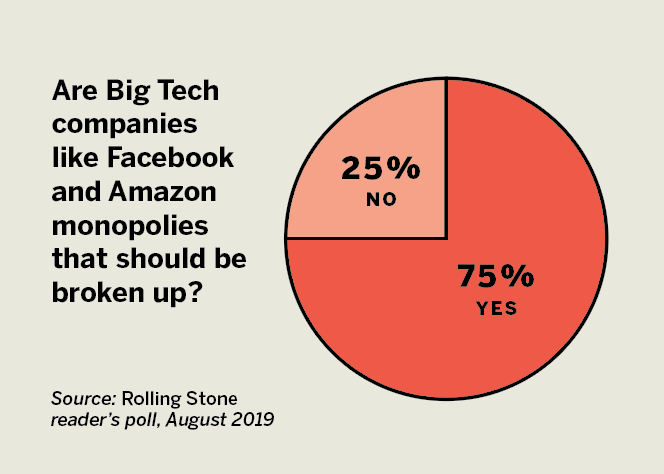

Stoller: They are resonating. More than 70% of the public wants to see antitrust investigations of Big Tech.

Crane: The American people have always felt deeply ambivalent about what former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis called “the curse of bigness.” On the one hand, there’s a Jeffersonian strand in the American consciousness that’s deeply concerned about large scale organizations—whether in business, government, religion or anywhere else. On the other hand, there’s also a Hamiltonian strand that covets the efficiency that comes with certain kinds of large-scale organizations. So even while we complain about the growing shadow of Big Tech, we love our “free” searches with Google, social networking with Facebook and two-day Amazon Prime deliveries.

Cohn: I don’t think people are ambivalent. If you look at the issues dominating the media right now, you’ll see just how much people care about the role these companies play in their lives. However, people are not seeing any viable way out of the current situation. We’ve long seen this in privacy issues—people want to protect their privacy when they are asked, but as a practical matter many have just given up. That means that folks who want a change must first convince ordinary people that it’s actually possible. It’s difficult given the lack of serious investigation and leadership in Congress and elsewhere.

How powerful and influential is the Big Tech lobby?

Taplin: Well, it’s astonishing how much money they spend. Google is the largest spender in terms of lobbying of any Fortune 500 corporation. And they don’t really rely on the government to fund them the way Boeing or General Dynamics does. But I would argue that things are changing. The very fact that the Federal Trade Commission levied a $5 billion fine on Facebook is a big change. Makan Delrahim, the assistant attorney general for antitrust, has opened an antitrust examination of both Google and Amazon, which says to me that something big has switched.

Carl: Yes, they’re very powerful and influential. They’re insidious because they tend to do a lot of their work in secret.

Lewis: All big companies have influential lobbyists, but an informed public can always balance that through grassroots action, by contacting Congress, by voting and by engaging agencies like the FTC and FCC. We’ve seen it work from one industry to the next.

Stoller: But the tech lobbyists are the biggest spenders in D.C., and they finance a large section of the academic world that studies privacy.

Crane: I think it’s a mistake to think about a powerful, unified “Big Tech lobby.” Google, Amazon and Facebook have some interests that are aligned, but many that are in conflict. Also, many other big players out there have their own lobbying agendas that are dead set against Big Tech—on net neutrality, for example, and many other issues. Also, Big Tech faced an unusual set of ideological currents—they have to contend both with anti-corporate progressives and forces on the right that see Big Tech as left-leaning and discriminatory toward conservatives. Yes, Big Tech companies have lots of political muscle, but there are many complex countervailing forces

as well.

The DOJ recently announced an antitrust review of Big Tech companies. How hard will it be for the government to win cases based on rising prices, particularly in light of Google and Facebook ostensibly providing their major services for free?

Carl: People in the scholarly, regulatory and political communities have urged us to take a broader view of monopoly power. There is plenty of intellectual precedent for not just looking at prices to determine consumer harm. Especially given the aggressive barriers they have put up to competitors who have wanted to enter the market. The privacy issue is also a major point of entry. Frankly, If you don’t think that the monopoly power of Google, Facebook, etc., is harming consumers, you’re not really paying attention.

@chrisjlewis

Lewis: Antitrust analysis has become too focused on consumer prices. This is too narrow a view for our current digital marketplace. Big data collection, powerful network effects and the cost of exclusion from a digital platform create market power regardless of an exchange of dollars. We need to improve antitrust law and increase enforcement under current law, but it will be a slow and uncertain process. Instead, new pro-competition regulations should be our first step toward addressing dominant tech platforms.

Stoller: It depends on the judge, but generally speaking it won’t be as hard as they think. Judges will be in the spotlight, and that is meaningful. Enforcers just have to bring cases, a lot of them.

Crane: There’s a popular misconception that the consumer welfare standard that governs antitrust today requires proof of rising prices to consumers. The Justice Department largely won its case against Microsoft in 2001 with evidence that—even though Microsoft was doing things like giving away its Internet Explorer browser “for free”—it was entrenching its monopoly position in the Windows operating system and chilling innovation. The Microsoft case is the blueprint for any antitrust enforcement agency or private plaintiff wanting to sue Big Tech today. It’s not an impossible road. But don’t expect a court to break up the company even if it does find liability under the antitrust laws.

Cohn: This is definitely a big hurdle, and it’s why some folks are looking for other solutions to Big Tech in addition to this government antitrust review strategy. But it’s important and useful even though it will be difficult. We need to ensure that antitrust gets updated for our time. That includes recognizing that there are issues other than the price of a good or service that can be a measure of harm.

What do you expect to happen before the 2020 elections?

Taplin: Don’t expect the government to dismantle these companies before then. But if they were forced to break up, the investors might make more money. I mean if you broke out the value of Instagram from Facebook or the value of WhatsApp from Facebook, the sum of the parts may be worth more than the companies as a whole.

Carl: Well, this antitrust investigation is long overdue,

but we will see if it leads to anything substantive. Some critics think DOJ is not really serious here, but I hope they’re wrong. I have friends in senior positions in DOJ who definitely recognize the scope of the problem here. Certainly, the way these companies have abused their monopoly power has been not just deleterious to consumers, but to this particular administration. The president largely says the right things in terms of big picture understanding, but we’ve got to go beyond words and Tweets.

Crane: Antitrust reform, not just focused on Big Tech but on other industries as well—including banks, airlines and beer—will probably be a second-tier talking point in the 2020 election cycle. Second-tier because it would take a truly extraordinary turn of events to make antitrust enforcement break into the top tier with gun violence, health care, economic growth, immigration policy, and the other most salient political issues. Whether antitrust even makes it into the second tier depends in large part on who wins the Democratic nomination. If it’s a candidate like Elizabeth Warren who has made antitrust one of her signature issues, antitrust will likely be on the table. If the nominee is Joe Biden, expect antitrust to recede as a campaign issue. After all, it would be awkward for Biden to run on a plank of “Oh my gosh, Big Tech is out of control due to lax antitrust enforcement” when he helped preside over an eight-year period when Big Tech became Big Tech. On the Republican side, look for Donald Trump to make an issue of antitrust occasionally and opportunistically, as he did with respect to AT&T/Time Warner. Fun times ahead!

Cohn: I think we will continue to see misguided attempts to undermine Section 230. When bad things happen in the world, it’s understandable to want to hold someone or something responsible. After all, we all want to be safe in our homes and in public places, and recent violence has shaken us all to the core. But it’s important to note that going after Section 230 is not directly aimed at the perpetrators of violence. It will reinforce the power of Big Tech, instead of protecting the powerless.

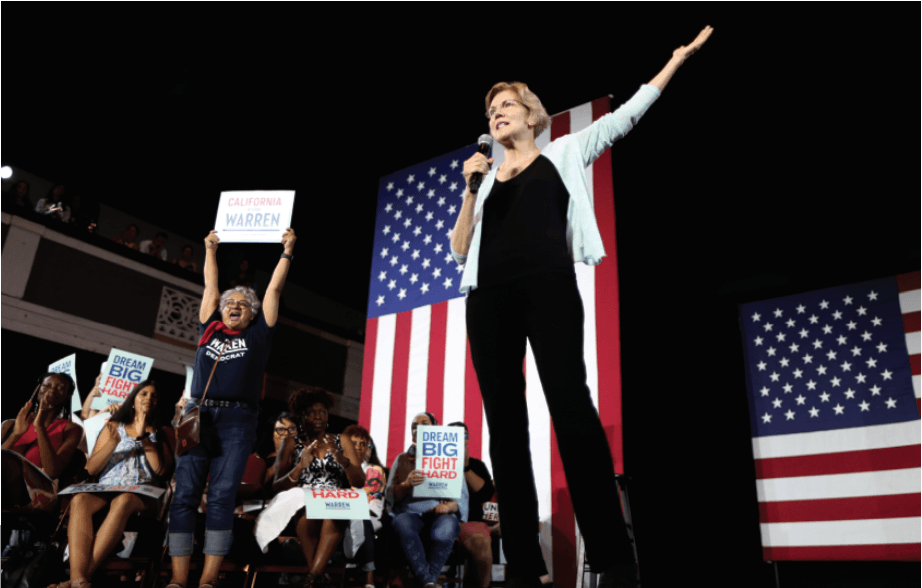

Elizabeth Warren “Has a Plan” for Big Tech

Presidential candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) warns that companies like Amazon, Facebook and Google have “bulldozed competition, used our private information for profit and tilted the playing field against everyone else.” That’s why she wants to break up Big Tech.

The first part of her two-part proposal calls for viewing large tech companies as “platform utilities.” Legislation would prohibit them from sharing data with third parties. Violators would be subject to a fine of 5% of their annual revenue and victims would have the right to sue the platform utility.

Part two outlines steps regulators would take to break up companies by negating recent mergers that Warren views as anti-competitive. In two possible examples, regulators might compel Facebook to divest itself of Instagram or require Amazon to sell off Whole Foods.