The CPI Doesn’t Lie, But It Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

New ways of measuring inflation may more accurately reflect consumers’ challenges

- Consumer price index (CPI) figures suggest inflation is easing, but many consumers still feel financially strained—reflecting a deep disconnect between official data and everyday reality.

- Wage growth has started to outpace inflation, but the cumulative loss in purchasing power has left many Americans struggling with record-high credit debt and weakened financial security.

- Considering the limitations of the CPI, there may be a need to develop alternative inflation gauges—such as PriceStats—to provide a more accurate picture of consumer inflation.

Rampant inflation has plagued the United States and much of the world ever since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s been severe enough to compel central banks worldwide to tighten monetary conditions and raise benchmark interest rates to levels not seen in decades.

But despite those aggressive measures, consumers continue to feel financially stretched and fatigued. Compounding the issue, the government’s method of measuring inflation is arguably flawed, aggravating the disconnect between policymakers’ intentions and the financial realities facing many Americans.

Let’s explore these issues and their broader implications.

A fragile victory over inflation?

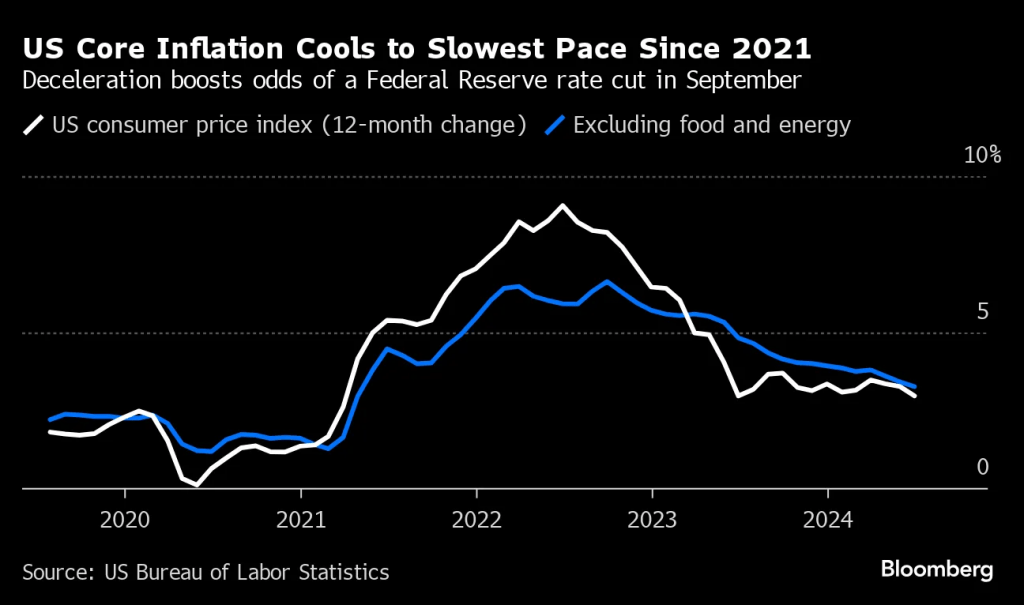

While no one is ready to declare “mission accomplished,” we’re seeing signs that the battle against inflation is yielding results. Inflation figures, such as the consumer price index (CPI), have receded from their peaks. In the United States, the annual inflation rate has fallen below 3.0%, a significant drop from highs of over 9.0% in 2022.

The decline in inflation has fueled speculation that central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, might soon pivot to a more dovish stance. Currently, the interest rate futures market anticipates a potential reduction in the Fed’s benchmark interest rates by 0.25% to 0.50% at their next meeting, scheduled for September.

Several other central banks have already begun cutting rates, signaling concern about inflation is easing andthe f ocus is shifting to the risk of an economic slowdown. The European Central Bank (ECB), for example, cut its benchmark rate by 0.25% in early June, lowering it from 4.00% to 3.75%. Similarly, the Bank of Canada pivoted earlier this summer, reducing its benchmark rate from 5.00% to 4.50% through two successive cuts.

Given these developments, one might assume consumers are all over the world are beginning to feel relief from the burden of high inflation. But economic data and consumer sentiment surveys suggest otherwise—at least for now.

Consumer finances continue to tighten

Despite the easing of inflation, many consumers are still grappling with the effects of the past few years of rapid growth in prices. The consumer price index (CPI) may show a decline, but that doesn’t necessarily bring an immediate sense of relief for the average consumer. Several factors contribute to this disconnect between the official data and consumer sentiment.

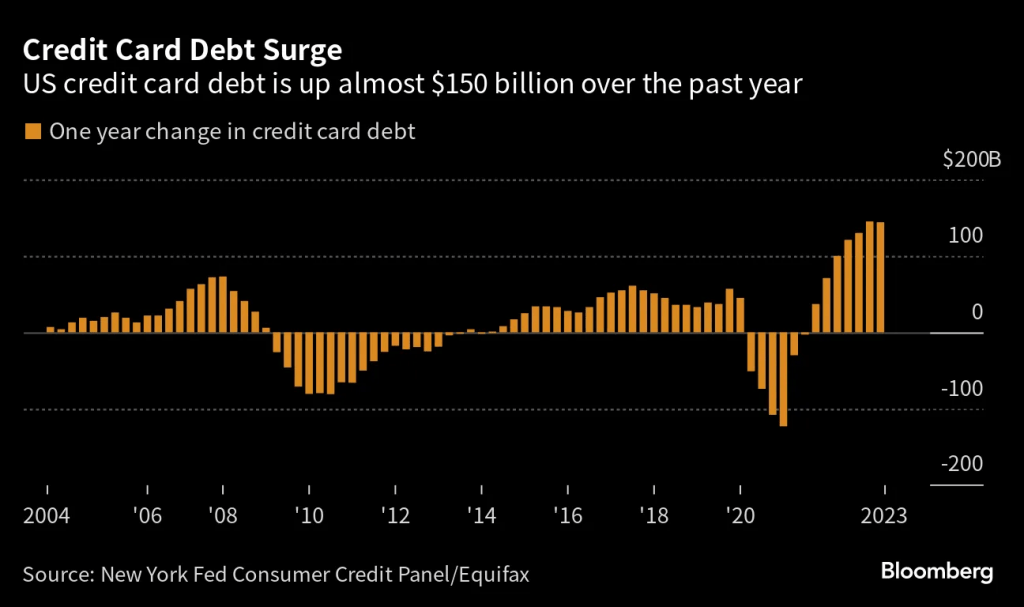

One major consideration is consumer fatigue from the prolonged period of high inflation. Even though CPI has moderated, the relentless increase in prices from 2021 through early 2023 has taken a toll on consumers’ financial well-being. Many households were forced to dip into savings or take on additional debt to cope with rising costs. As a result, credit card balances have surged to record-high levels, further exacerbating financial strain.

Another key to this narrative has been the uneven nature of price changes across different sectors of the economy. Energy prices, for instance, have come down significantly in the wake of the pandemic, but the cost of housing and healthcare have increased persistently.

By measuring averages, the CPI can mask these differences. If the rent is rising or medical expenses are increasing—expenses that constitute a large portion of a family’s monthly budget—they may not notice the overall decline in inflation as reflected in the CPI.

Wage growth lags, exacerbating consumer pain

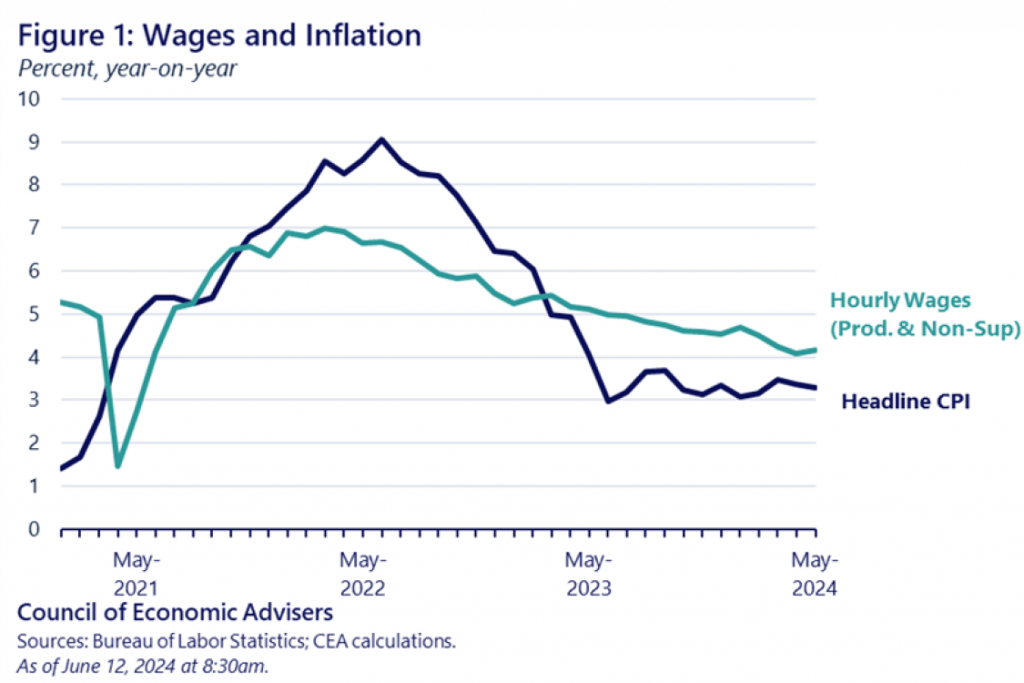

Wage growth plays a crucial role in shaping how consumers perceive inflation. Over the last several years, wages have grown more quickly but have not always kept pace with the rate of inflation, especially during the peak periods of price increases in 2021 and 2022.

The growth of wages is now outstripping inflation (illustrated below), but the cumulative loss in purchasing power from previous years means many consumers are still feeling financially stretched. So even though wages are theoretically rising, the corresponding recovery in “real wages” (wages adjusted for inflation) has been slower. It leaves many consumers feeling their financial positions have weakened.

Another factor is that consumers’ perceptions often lag behind actual economic conditions. It happens because of disappointing personal experiences, the long-term psychological toll of enduring historically high inflation, and confusing or misleading media reports.

That stark reality has been underscored by the recent decline in consumer confidence. The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index recently dropped to an eight-month low, registering a reading of 66. This decline marks a 2.2-point decrease from June, reflecting consumers’ ongoing concern about their financial outlook despite the purported easing of inflation.

Existing inflation gauges are imperfect

While observers has long relied upon government inflation metrics like the CPI to gauge the economy’s health, those measures often fall short of capturing the full reality of consumers’ experiences. The CPI, which tracks the prices of a fixed basket of goods and services, is updated only periodically, leading to delays in reflecting shifts in consumer behavior and sentiment.

Moreover, when prices rise, consumers often substitute cheaper alternatives for more expensive goods. But this substitution isn’t immediately (or fully) reflected in the CPI, leading to a potential misalignment between the index and what consumers are actually paying.

The method used to adjust for changes in the quality of goods and services, known as “hedonic pricing,” can complicate the picture . While it helps to account for improvements in products—like a more advanced smartphone—such adjustments can obscure the true increase in costs.

The CPI also excludes certain significant costs, such as investment goods, income taxes and regional price differences—the latter of which can vary widely. These omissions mean that the CPI may not fully capture the inflationary pressures faced by all consumers, particularly those in high-cost regions, or those whose expenses fall outside the scope of the index. This can lead to a situation where the official inflation rate appears lower than what many consumers experience in their day-to-day lives.

Potential remedies

In response to the limitations of CPI, new metrics are emerging that are intended to fprovide a more accurate and timely reflection of inflation. The Billion Prices Project at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is one such effort.

The project collects real-time price data from millions of online retailers, offering a broader and more immediate view of inflation trends. Unlike the CPI, which is updated monthly, it continuously tracks prices, capturing fluctuations in real-time. This data offers a more accurate picture of the inflation consumers are facing in the moment, as opposed to a retrospective snapshot.

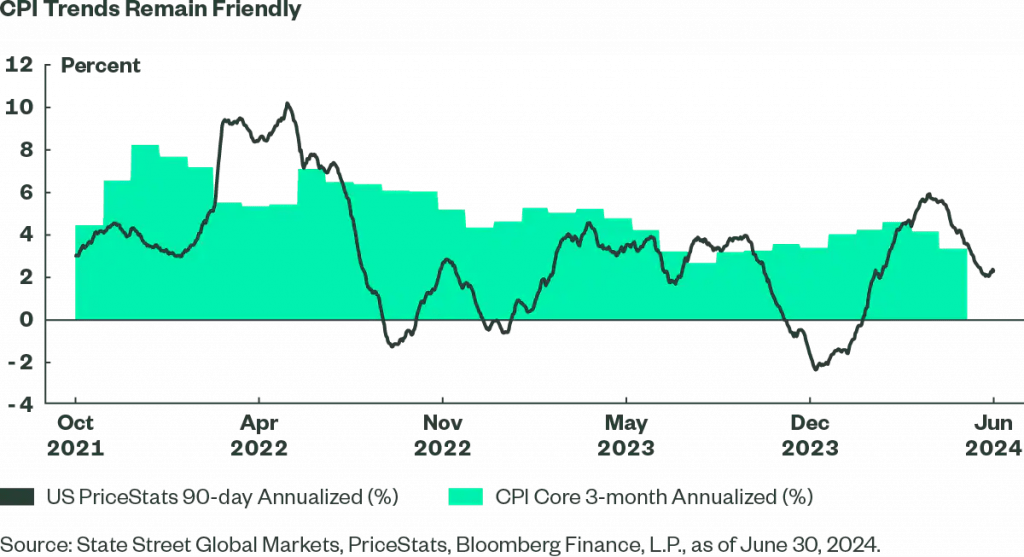

The Billion Prices Project, now operating under the “PriceStats” umbrella, has revealed the post-COVID spike in inflation was more severe than the CPI indicated. These variations in the chart below show the value of alternative inflation tracking.

By incorporating a broader range of goods and services (and continuously updating their associated prices), PriceStats addresses some of the limitations of traditional inflation gauges. And as these alternative metrics evolve, they hold the potential to not only complement but also significantly enhance economists’ understanding of inflation.

With a real-time, comprehensive view of price changes, tools like PriceStats should enable policymakers to respond more quickly and accurately to ever-shifting inflation trends. Moreover, the deep insight afforded by this data should help develop economic policies that may alleviate some of the financial challenges faced by American consumers.

Andrew Prochnow has more than 15 years of experience trading the global financial markets, including 10 years as a professional options trader. Andrew is a frequent contributor of Luckbox Magazine.

For live daily programming, market news and commentary, visit tastylive or the YouTube channels tastylive (for options traders), and tastyliveTrending for stocks, futures, forex & macro.

Trade with a better broker, open a tastytrade account today. tastylive, Inc. and tastytrade, Inc. are separate but affiliated companies.