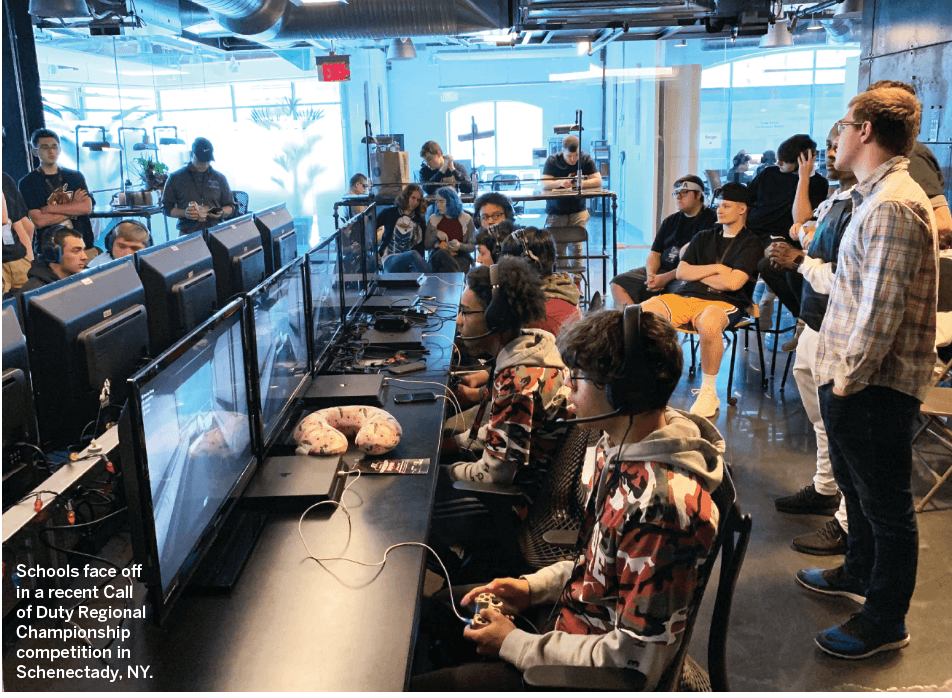

Young Money

With esports prize pools in the millions, where does the money flow? Meet a past and present pro

This Med Student spent his gap year as an esports pro

After devoting a gap year between high school and college to playing StarCraft II professionally, Conan “Suppy” Liu, aka “Superiorwolf,” went back to the books, completing a bachelor’s at the University of California at Berkeley.

But he didn’t stop there. Now, he’s studying medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of the Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

When it comes to meeting the high cost of so much education, it can’t hurt that Liu racked up $75,000 in prize money during his pro esports days, having his best year at age 19.

A seasoned pro with upside

Understandably, teenaged pros generally don’t have much previous experience of the world when they hit the big time, Sunderhaft, notes. “I’ve never worked a conventional job in my life,” says the 21-year-old who’s been making his presence felt on the professional scene since age 16.

Nefarious teams can take advantage of such inexperience, some observers claim. One young pro, Turner “Tfue” Tunney, recently sued Team Faze Clan for allegedly limiting his business opportunities, appropriating a huge share of his earnings, and encouraging him to gamble and drink underage, according to published reports.

But Sunderhaft reports that he hasn’t experienced the fate described in Tenny’s headline-making lawsuit. “My sponsor, (mobile networker) Ting, has been easy to work with and reliable regarding salary,” Sunderhaft says. In the past four to five years, he’s reportedly earned just shy of $440,000 in 156 tournaments.

That degree of success required extraordinary measures. After graduating from high school Sunderhaft skipped college and moved from New York to South Korea to hone his skills on StarCraft, because that’s where that game’s played with particular intensity.

“I practice three to four hours a day, which is standard for StarCraft,” Sunderhaft says of his current regime. “I’d imagine the very popular games have players with strict practice schedules to optimize their entire day, just as StarCraft did when it was at its peak about eight years ago.”

Looking to the future, Sunderhaft plans to “simply enjoy StarCraft for as long as it stays a viable esport.” But he doesn’t blame other professional video game players for dreaming big. “Esports offers endless opportunities for ordinary people,” he says. “I’ve been grateful ever since I started almost 10 years ago.”