Inoculating the World Against Recession

The Covid-19 pandemic plunged the world into deep recession as nations retreated into lockdown to contain the viral spread. But monetary and fiscal officials responded to the crisis swiftly and powerfully, based on the collective wisdom they gained during the 2008 global financial crisis and its aftermath. This time, world leaders took bold action to avoid a sluggish recovery.

The Federal Reserve Bank slashed its policy rate to 0% and quashed early signs of credit market stress with open-ended quantitative easing. It supplemented those actions with an assortment of targeted lending facilities and a pivot to average inflation targeting. That allows policymakers to tolerate periods of inflation above the target 2% following spells of undershooting and thereby to remove stimulus more slowly once a rebound is afoot.

Other top central banks followed suit, slashing benchmark interest rates and introducing a host of non-standard easing schemes, from asset purchases injecting liquidity into markets and repo operations capitalizing banks to yield curve control regimes capping bond rates. Still, the U.S. dollar is the dominant transactional currency worldwide, so the Fed’s effort was most crucial.

A similar story can be told on the fiscal side. Most governments loosened their purse strings to some degree, but the United States has done the most. Congress spent a whopping $4 trillion on stimulus before Joe Biden took office as president, and his administration has pushed through another $1.9 trillion in spending. That puts the total at a staggering 25% of GDP in 2019, the year preceding the COVID-19 outbreak.

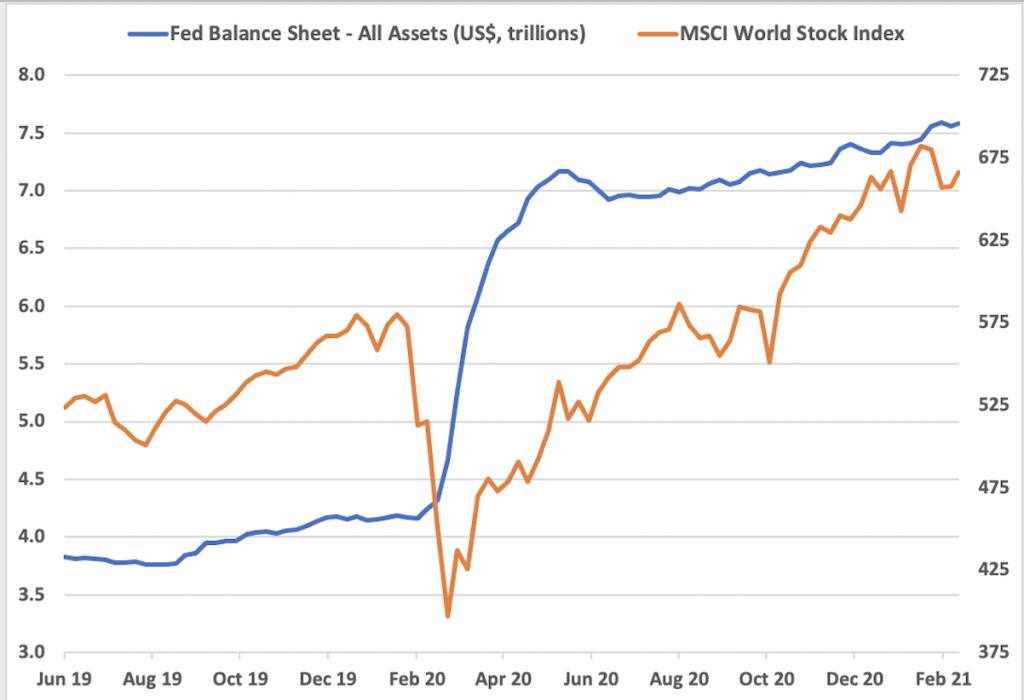

The scale and speed of the response outstrip the actions of 2008. The Fed grew its balance sheet by $3.6 trillion over the nearly seven years between August 2008 and February 2015. It added an analogous $3.3 trillion in just 12 months this time around, from February 2020 to 2021. The fiscal response to Covid-19 has dwarfed that of the Great Recession by about 2.5 times in the United States. For some countries, the difference has been nearly 10-fold in share-of-GDP terms.

A successful stimulus

On balance, the stimulus efforts have delivered. The JPMorgan Global Composite PMI gauge of economic activity calculates the pace of expansion in the manufacturing and services sectors as the fastest since mid-2018, before the U.S.-China trade war started to take hold but after the Trump administration’s behemoth tax cut juiced performance in the world’s largest economy. Economists expect world GDP to add 5.6% this year, the biggest rise in decades.

Policymakers appear ready to keep the pedal to the metal. In the United States in particular, Team Biden plans an ambitious agenda calling for big-splash spending—like $2 trillion on green energy in his first term, for example—while the Fed has emphatically signaled that tightening is nowhere in sight. This seems to be informed by another lesson from the post-2008 recovery: Hefty stimulus will not revive runaway inflation.

Wrong about inflation?

This lack of fear about inflation is not wholly unreasonable. Data from the International Monetary Fund shows price growth has steadily declined since the mid-1990s, with the global Consumer Price Index settling on a narrow range, averaging a relatively benign 4% during the past 20 years. The Great Recession marked a brief hiccup rather than a structural departure from that norm. Nevertheless, financial markets are demonstrably concerned that this time will be different.

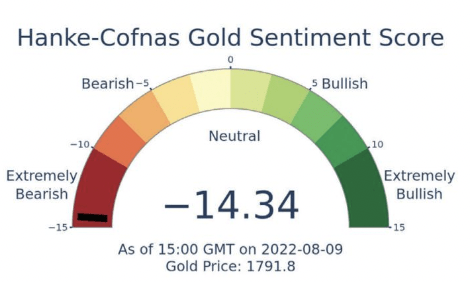

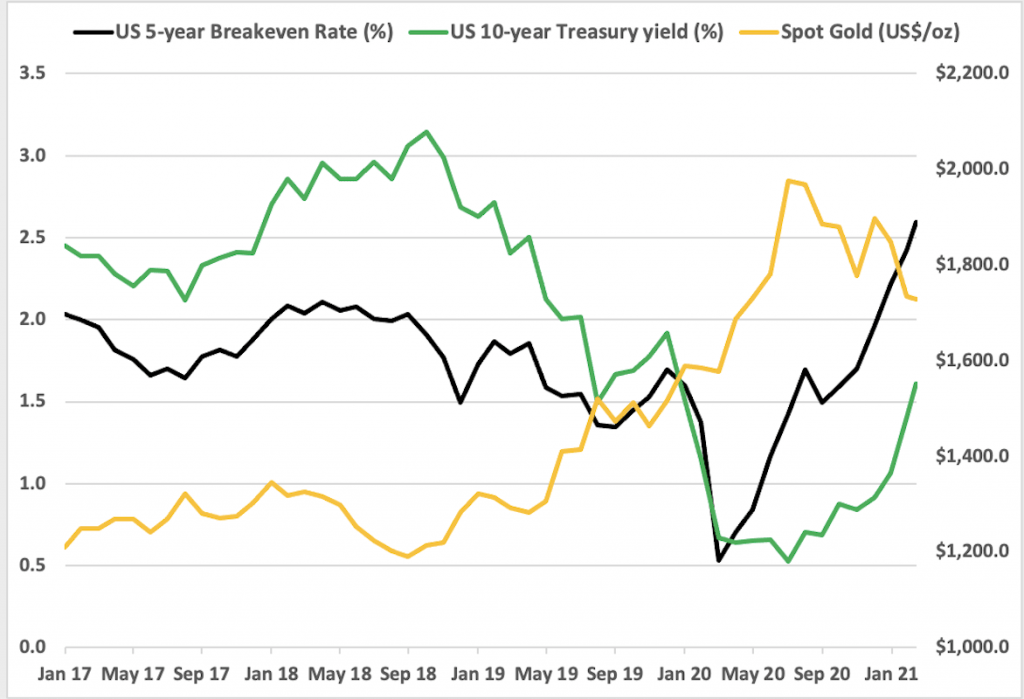

Tellingly, the five-year breakeven rate—a measure of medium-term price growth expectations derived from the spread between nominal and inflation-adjusted bond yields—now sits at its highest point since 2007. Borrowing costs have mounted a spirited rally against this backdrop, while anti-fiat gold prices have trended lower, signaling that investors are worried about a sudden about-face from the Fed that meaningfully brings forward the timeline for stimulus withdrawal.

That makes sense. The fiscal boost on offer now surpasses that of the prior crisis by a long mile, while the flood of central bank liquidity has arrived far more quickly than before. Accelerating vaccination and easing restrictions it portends promise to unleash a flood of pent-up demand that didn’t occur in the wake of the 2008-2009 downturn. A built-in price premium reflecting lingering friction along the critical U.S.-China leg of the global supply chain remains.

Inflation bets boost yields

What all of this means for foreign-exchange markets seems relatively straightforward. A repricing of U.S. monetary policy bets away from the dovish edge of the spectrum appears likely to bode well for the recently battered U.S. dollar. It was trading at a two-year low as recently as late February as firming risk appetite meant traders prized returns over liquidity. Gains may be most pronounced against currencies where an ultra-dovish policy bias was built-in before the Covid-19 outbreak and thus appears likely to remain, like the euro.

Indeed, the European Central Bank had already pushed its target lending rate into negative territory and launched assorted non-standard easing programs when the pandemic struck. The Eurozone has also fared worse than other major economic areas since the virus appeared. While the United States and China have returned to growth, economic activity in the currency bloc continues to contract. EUR/USD has pointedly recoiled from chart resistance against this backdrop. Deeper losses may follow.

Ilya Spivak is head strategist for Asia-Pacific markets at DailyFX, the research arm of retail trading platform IG. @ilyaspivak