Trading the Prospect for a Nationwide Railroads Shutdown

Approximately 115,000 railroad workers in the U.S. are scheduled to go on strike starting Dec. 9, unless a last-minute deal is struck between railroad owners and the industry’s 12 major unions

Two months ago the U.S. government intervened to help avert a nationwide strike in the railroad industry. Unfortunately, railroad workers in the U.S. haven’t agreed to the terms negotiated back in September, and may walk off the job as soon as Dec. 9.

A nationwide strike—which would paralyze a significant portion of the U.S. supply chain—became more likely after two key railroad unions officially rejected the deal on Nov. 21. That means eight railroad unions voted in favor of the deal, while four rail unions voted against it. This result is especially important for railroad workers because, in this niche of the economy, unions operate under a collective bargaining concept known as “me too.”

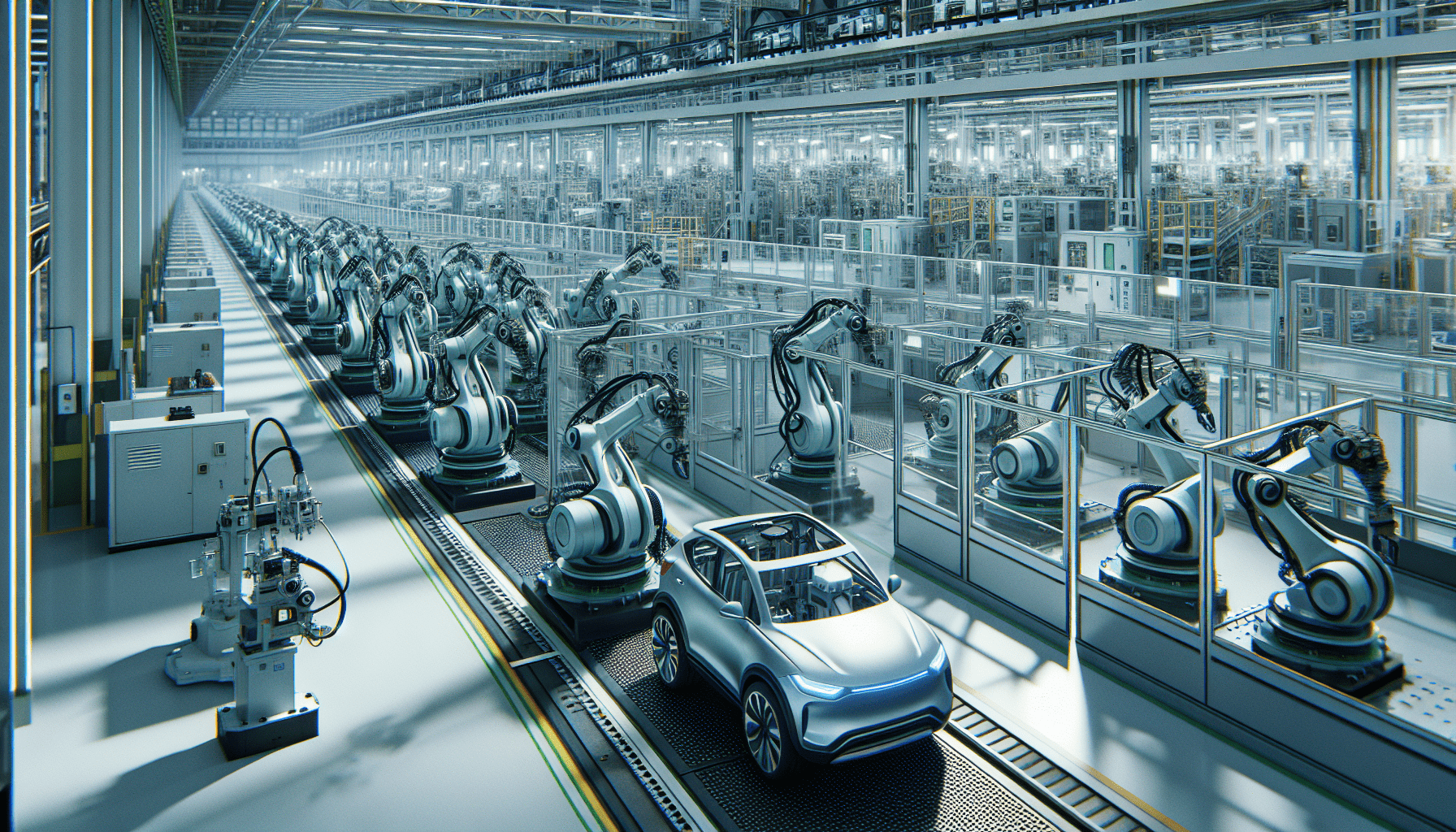

So, if one of the 12 total railroad unions walks off the job (i.e. strikes), the other 11 are compelled to follow suit. These days, the total number of railroad workers in the U.S. is estimated at roughly 115,000, which altogether operate a fleet of roughly 7,000 freight trains.

If a deal isn’t agreed upon before Dec. 9, it would represent the first significant railroad strike in the U.S. since 1992. That one lasted only two days because the government intervened, and ultimately forced a solution upon the industry.

The railroad sector is somewhat unique because it plays such a critical role in the U.S. economy. Today, it’s estimated that a nationwide shutdown of the entire freight-related rail system would cost the country upwards of $2 billion/day in lost productivity.

That figure doesn’t account for the fragile nature of the existing U.S. supply chain. If the rail-based freight network were knocked offline due to a worker strike, it’s very difficult to predict how that might ultimately impact the underlying economy.

For example, an estimate provided by the American Trucking Association suggests that an additional 460,000 long-haul trucks would be required to offset the impact of 7,000 idled freight trains. That figure far outstrips the supply of available trucks, much less the drivers necessary to operate them.

Source: railroads.gov

Rising likelihood of congressional intervention

The railroad industry in the U.S. is roughly 200 years old, and through that long history there have been plenty of battles fought between railroad owners and railroad workers.

Some of the most famous strikes in railroad history include the Great Upheaval in 1877, as well as the Pullman Strike in 1894. The Great Upheaval was catalyzed by two consecutive 10% cuts in the salaries of railroad workers over a period of eight months. As a result, roughly 100,000 railroad workers went on strike, and nearly 100 lost their lives. Unfortunately, little was accomplished in terms of real concessions.

The Pullman Strike was a lot more chaotic and ultimately affected around 250,000 railroad workers. This strike started when George Pullman abruptly cut wages by 25%. Ultimately, the strike was stopped via court injunction, but many credit this event for the creation of the Labor Day holiday in the U.S.

Strikes have been far less common in the last 75 years due to the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. This legislation restricts the activities and powers of labor unions, and specifically authorizes the president to intervene in strikes (or potential strikes) that create a national emergency.

Today, however, the Railway Labor Act (RLA) tends to guide the U.S. government’s response to disagreements between owners and workers. This legislation empowers Congress to intervene in railroad-related labor disputes to help ensure that undue harm isn’t done to the underlying U.S. economy.

The RLA allows strikes to occur, especially for major disputes—assuming that railroad workers (through their unions) have exhausted the negotiation and mediation procedures outlined in the RLA. On the other hand, the act also allows Congress to force a new labor contract on both parties, or to extend the existing labor agreement.

As such, Congress will have options available to it should a strike in fact materialize on Dec. 9.

Source: railroads.gov

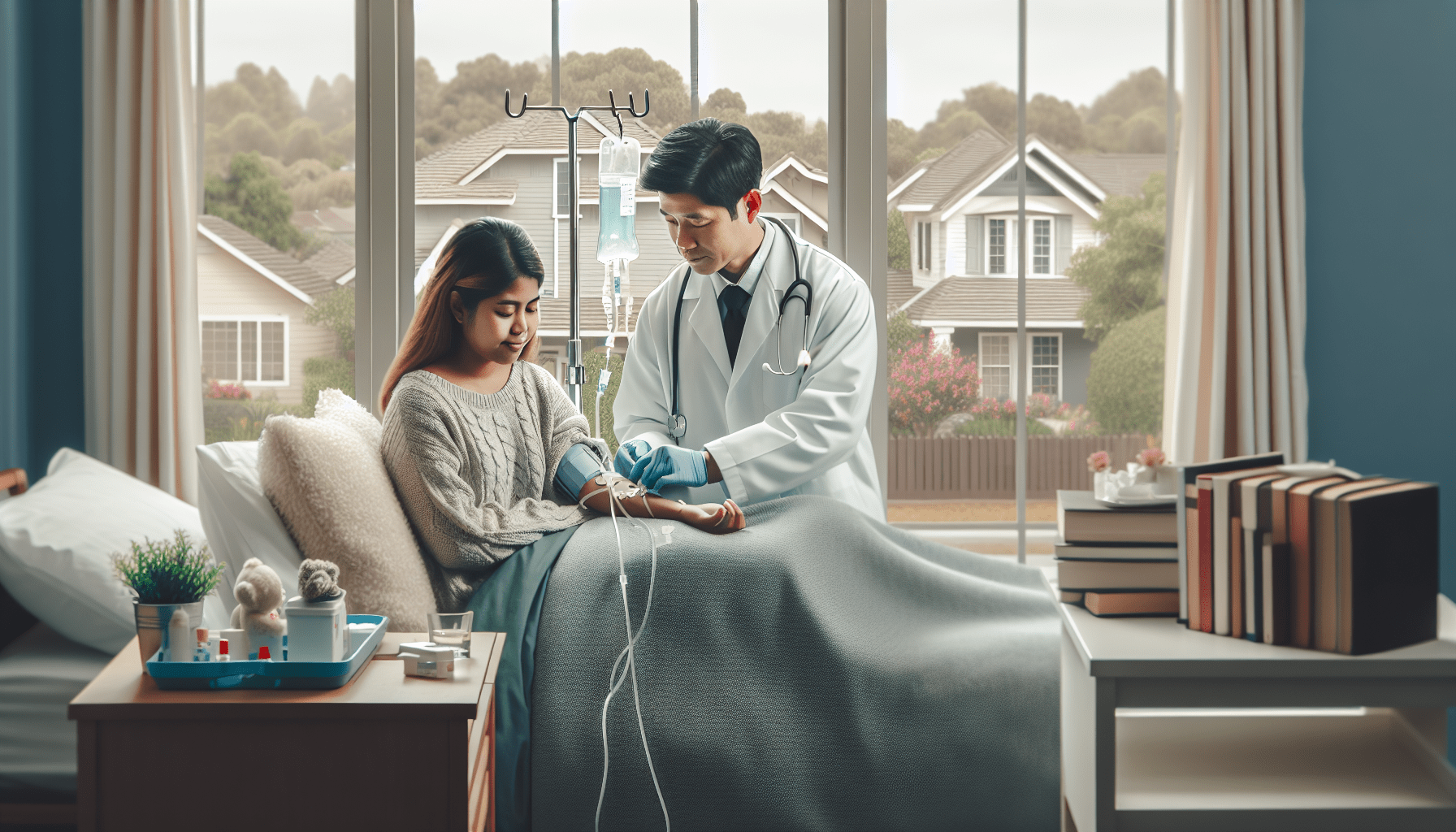

The current railroad strike isn’t only about wages, but also about working conditions. Based on recent negotiations, some of the most critical sticking points involve sick leave and understaffing—both of which have contributed to serious quality-of-life concerns for workers within the industry.

At present, the package offered to railroad workers provides them with one additional day off, as well as backpay, bonuses and a 14% raise. The backpay and bonuses are said to equate to a payment of roughly $11,000 for each existing railroad union member—assuming the deal is ultimately agreed upon (or forced upon them by Congress).

Trading the railroad sector

At the heart of the current dispute between railroad companies and railroad workers is the record profits booked by the industry in recent years.

Citing an example, BNSF Railway booked an annual operating income of roughly $9 billion in 2021—an all-time record for the railroad. It also represented a 14% increase from 2020. BNSF was acquired by Berkshire Hathaway in 2009, and is not publicly traded.

Union Pacific (UNP), which like BNSF is one of the country’s largest freight carriers, had similar success in 2021. Last year, Union Pacific booked about $9 billion in operating income—eerily similar to BNSF 2021 results.

According to an analysis conducted by A More Perfect Union, the operating incomes of the country’s largest railroads have tripled over the last two decades, while the percentage of revenue spent on labor has declined by double digits.

The aforementioned financial analysis indicated that the operating margins for large railway carriers like BNSF and Union Pacific were in the 15% range back in 2001. But today, those operating margins have spiked to over 40%.

Railway workers have noted these soaring profitability figures, and this likely helps explain why they are seeking a new labor agreement. A More Perfect Union noted that while railway revenues have doubled over the last 20 years for many carriers, the total amount spent on labor has only increased by about 10%, on average.

Moreover, it’s estimated that the railroad industry has paid out nearly $200 billion through stock buybacks and dividends since 2010. That’s a significant windfall for investors in the sector, and stock valuations have responded in kind.

The list below highlights the five-year stock returns for some of the most visible railroad stocks trading on U.S. exchanges:

- Canadian Pacific (CP), +130%

- Canadian National (CNI), +57%

- CSX Corp (CSX), +88%

- FreightCar America (RAIL), -76%

- GATX Corp (GATX), +92%

- Greenbrier (GBX), -17%

- Norfolk Southern (NSC), +93%

- Trinity Industries (TRN), -10%

- Union Pacific (UNP), +80%

The above data illustrates how shares in the railroad freight operators (CP, CNI, CSX, NSC, UNP) have performed much better than shares in the companies that provide services to the railroad industry (RAIL, GBX, TRN).

Going forward, investors and traders may want to monitor railroad stocks closely, because the ongoing labor dispute could create new opportunities in the sector, as well as the broader U.S. stock market.

To follow everything moving the markets during the remainder of 2022, including the looming railroad workers’ strike, monitor TASTYTRADE LIVE, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.