A Textbook Case Study of Oligopolies

Spending on course materials is declining, but that doesn’t mean textbook prices are going down. Students just aren’t buying them.

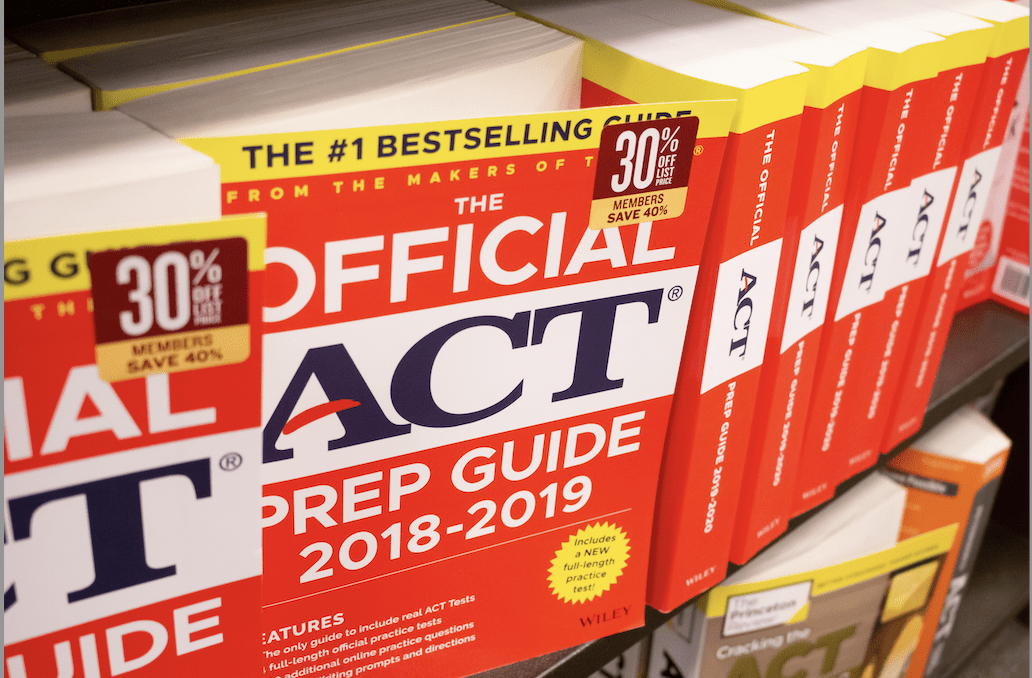

Trudi Radtke’s first day of community college—like most students’—included a trip to the campus bookstore. For a first-generation college student, it was an exciting rite of passage. But rather than leave with any books, Radtke left with sticker shock.

“They rang them all up, and they were like, ‘It’s $700,’” Radtke told Luckbox. “My mouth dropped open.”

The cost of textbooks often stands in the shadow of the cost of tuition—especially at pricey private colleges and universities. Yet, what happened to Radtke is far from unique.

Nearly two-thirds of college students nationwide reported in 2020 that they skipped purchasing a textbook despite concerns about their grades, according to the U.S. Public Interest Research Group’s Education Fund. That’s a small increase over the 63% of students who skipped purchasing one during the same period the year before.

Today, Radtke works as a project manager for the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition (SPARC), a nonprofit advocacy organization focused on expanding open and equitable access to research and education. Specifically, they manage inclusiveaccess.org, a website designed to raise awareness about a new and growing automatic textbook billing model called inclusive access.

Although it makes sense that tuition gets the spotlight in discussions about the cost of higher ed, Radtke said, it’s just one piece of a package of problems that can make academic success an overwhelming financial challenge.

“If a student can’t buy a textbook, they’re not going to be as effective in that course,” Radtke said. “That’s going to affect their academic performance, which is going to affect their GPA, which is going to affect their grant status. It’s all so interconnected.”

So how did textbooks get so expensive in the first place?

“To understand the situation,” Radtke said, “you have to understand the market.”

They explained it this way: Students are a captive market for textbook publishers because required reading typically isn’t discretionary. Plus, there’s a principal-agent problem. Students have no say in which course materials will be assigned for their classes. Meanwhile, administrators and faculty are solicited by publishers and ultimately make those decisions.

It doesn’t help that there isn’t a lot of competition in the textbook-publishing industry. According to Marketplace, just three publishing companies control 80% of the U.S. textbook market: Pearson, Cengage and McGraw Hill.

Neither Pearson nor McGraw Hill responded to several requests for comment for this piece, but Cengage Academic’s executive vice president and co-general manager Nhaim Khoury did. And Khoury didn’t sugarcoat the past practices of publishing companies.

“For too long, the textbook industry pushed outdated business models that didn’t put students first,” he said via email. “Students voted with their wallets and chose more affordable options. For years, publishers, including Cengage, were part of the problem.”

It’s a problem Cengage has been working to address with an all-access digital eTextbook subscription platform called Cengage Unlimited. Students can access all of Cengage’s eTextbooks, online learning platforms, study guides and more for $125 for a four-month term or $190 a year. Students who prefer printed materials can access up to four print rentals at no added cost except a shipping fee.

“As long as there are customers who want print,” Khoury wrote, “we will continue to provide it.”

While models like Cengage’s may be a step in the right direction, there’s a lot of ground to cover.

An NBC review of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data found that from January 1977 to June 2015, textbook prices rose 1,041%. That’s over three times the rate of inflation for that period. Last school year, the average price of books and school supplies for college students was $1,240, according to the free online college advisory service collegedata.com.

But don’t take collegedata.com’s word for it. Colleges and universities themselves don’t shy away from the fact that textbooks are expensive. Northwestern University recommends setting aside nearly $1,600 for books and supplies for the 2022-23 school year. The University of California at Berkeley recommends $1,140.

However, some sources are quick to dispute those numbers. An often-referenced report conducted by Student Monitor—a research service that targets the college student market—found that student spending has been dropping significantly in recent years. A press release about it published on the Association of American Publishers (AAP) website was even headlined “A Victory for Affordability: Student Spending on Course Materials Declines 22% During the 2021-2022 Academic Year.”

Looking at the bigger picture, the report found a 44% decline in student spending over the past decade.

“I would attribute the decline to two factors,” Kelly Denson, AAP’s vice president of education policy and programs, said via email, “first, publishers have made both affordability and quality a major focus, and as part of that effort they’ve introduced a wide range of cost-effective options, including Inclusive Access programs, offered at the lowest market rates according to US Department of Education federal regulations.”

Second, Denson wrote, students know what’s best for their individual and financial needs, and giving them the option to choose has contributed to the decline.

But some take issue with the language used in Student Monitor’s report.

“The numbers don’t tell the whole story,” said Nicole Allen, director of open education for SPARC. “Student spending is not the best measure of the impact that textbook costs are having on students, and that’s for a few reasons.”

Chief among them, Allen said, is that spending isn’t synonymous with cost. Focusing on student spending doesn’t address the fact that many students don’t buy all of their required course materials. Students who don’t buy any textbooks, for instance, technically don’t spend any money.

When asked about the BLS data pointing to a 1,041% increase in prices for textbooks from 1977 to 2015 and what the publishing industry has done to address it, the AAP’s Denson again pointed to reports about student spending.

“The three leading sources—student watch, student monitor and college board—all show a clear decline in student spending on course materials,” Denson wrote. “The recent data from these reputable sources contradicts the BLS data which dates back 5-7 years ago.”

Luckbox reviewed the Student Monitor report for the spring 2022 term. It also found that students acquired only 38% of their required course materials on average, that 16% of students have dropped—or haven’t taken—a course because of the cost of its course materials, and that more than two-thirds of students agreed the cost of textbooks is excessive.

But affordable options are out there. Besides the all-access subscription initiative launched by Cengage, other alternatives are gaining traction to help students cut costs.

Advocates like Allen and Radtke champion open educational resources, or OER, as a possible solution. These resources typically grant an open license, such as Creative Commons, that allows anyone to use, adapt and share them freely. It’s a popular idea among students, too.

Revisiting the Student Monitor report, 83% of students said using OER materials is more appealing than purchasing or renting an eTextbook. More than two-thirds said they believe the quality of an OER textbook is just as good or better than an eTextbook.

The biggest barrier to OER, Allen said, is that it disrupts the way the system has long operated.

“Every new technology goes through that phase where you’re transitioning from the world that was, where you had to print and ship a book to every student you wanted to educate,” she said, “to the world that is, where we can access a vast amount of information instantly over the web … for a much lower cost than has ever been possible before.”