The Next Generation of Gamers

The old guard of pro gamers (the 20-somethings) have enjoyed big paydays, but a crop of young talent is rising up behind them

The timing must have been right for the High School Esports League. In a few short

The phenomenon is continuing to build momentum as some schools elevate their esports clubs to full-fledged varsity sport status, says Mason Mullenioux, the league’s CEO.

It all began with an origins story that belongs in a time capsule. Mullenioux and his childhood friend Charles Reilly were searching for their place in the world after graduating from Old Mizzou (the University of Missouri at Columbia) in 2010. They were set adrift as the nation suffered through the third year of the Great Recession.

“No one could find a job anywhere,” Mullenioux recalls. “We were delivering pizzas for Papa John’s, and we both lived with our parents. When we got off work we’d go over to Charlie’s house and think about what we were going to do.”

The only plan they devised that actually appealed to them was launching an esports league for high school players. So, they started the league in 2012 as an unpaid hobby. They soon found high schoolers had a lot of interest, so they kept at it.

In the meantime, both found substantial jobs. Mullenioux began working as a project manager for Sprint, and Reilly managed the parts department at a Subaru dealership. But passion prevailed, and in a few years the league grew into a business based in Kansas City. When they found themselves taking too many league-related calls at work, they quit their day jobs and devoted themselves to the league.

Probably because the timing was so right, Mullenioux and Reilly soon discovered that someone else was doing exactly the same thing at the same time and giving it the same name. Half a continent away in San Francisco, Aaron Hawkey also had started a league. Instead of competing, the three joined forces, with Mullenioux becoming CEO, Reilly taking on chief operating officer duties and Hawkey serving as chief technology officer.

They raised money from friends and family to build a tech platform, and by 2016 the technical backbone was in place and the time had come to begin charging for league membership. But the fees weren’t just a profit center, according to Mullenioux. “We needed the students to take it seriously,” he says of the league’s early days. “They needed to have skin in the game to finish the season.”

Now, the league’s 15 full-time staffers are scattered across the nation in Kansas City, San Diego, San Francisco, Texas and Maine. The five part-timers and the volunteers are similarly decentralized. The geographic diversity came about by chance but has worked to the league’s advantage because its officials can travel conveniently to conventions anywhere in the country.

But the staff can’t do it all alone. The league stipulates that a teacher or coach from each school must take responsibility for the league’s club. Each school also has to supply written approval of the club as a recognized school activity.

About 85% of the league’s players belong to school-sanctioned clubs, and students at schools without clubs can join free-agent leagues. The free agents often help start clubs at their schools, Mullenioux notes. More often than not students launch the clubs. “They know who the cool teacher is,” and can enlist help. Some teachers become enthusiastic, and that leads to the highest success rate, Mullenioux says. Those teachers “seek students, make morning announcements and pass out fliers,” he adds.

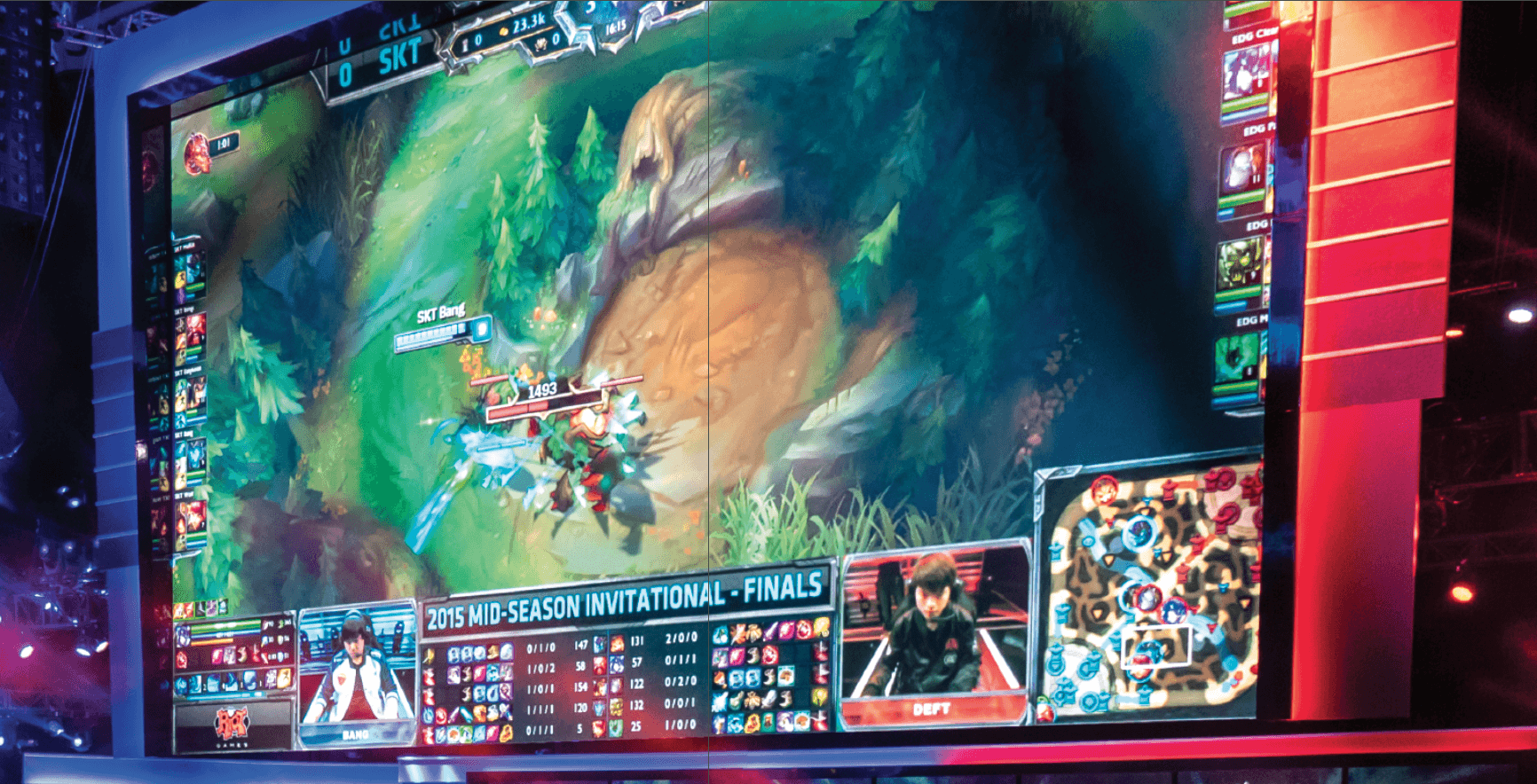

The league can charge teams or students to participate. Students can pool their membership applications to qualify for discounts. Sometimes school budgets cover the fees. The league charges players $30 per season, which is less than competing organizations collect, according to Mullenioux. Overwatch and League of Legends are two of the most popular games at the moment, he observes. Nine games are available for league play, but the league tests new games during the slow seasons and adopts them if they prove popular.

Clubs have formed at schools in all types of places, but suburban schools have been most likely to join the league, Mullenioux says. Rural locations may lack good internet connectivity and have long travel times to matches. Inner city schools and students may lack the funds. The league is setting up a not-for-profit organization to help underwrite the costs for schools and students in need.

So far, high school and college esports teams aren’t attracting the huge viewership that pros generate. A few friends and family members typically watch high school esports matches, but the competitions don’t attract the cheering crowds that pack the stands for football or basketball. “We’ re going to get there,” Mullenioux predicts, “but it will take a little more time.”

How much more time? In three to five years a significant number of high schools will field varsity esports team and will attract heavy viewership, Mullenioux says. That should generate enough excitement to take high school esports to the next level, he maintains. A few schools have already established esports arenas, and some states have taken steps to become sanctioning bodies.

Outstanding competitors in organized high school leagues can attract the attention of college recruiters at schools that offer esports scholarships. “All the college eyes are on us,” Mullenioux maintains. “There are scholarships out there that are unfilled because they can’t find kids to

Fast Times at Bay Shore High

At most high schools, the quiet kid who aces AP calculus might never have a conversation with the star quarterback. But at Bay Shore High School on Long Island, that unlikely duo just might become friends after discovering they both play StarCraft.

It’s something that happens in the school’s video game club, which was designed with a community side as well as a competitive side, says Ryan Champlin, a senior who’s credited with organizing the club two years ago.

The club’s competitive side has scored some wild successes, too, with the Call of Duty team going undefeated in North American competition and the Rainbow Six team occupying a spot in North America’s Top five teams since its inception.

One Bay Shore student, 17-year-old Justin “jstn” Morales, can’t compete on the school’s teams because he already plays professionally for the powerhouse NRG squad. He’s been bringing home serious prize money while remaining admirably humble, Champlin says. (Morales has earned $76,854 in prize money in 11 tournaments, according to the Esports Earnings website.)

Every senior in the club has received a college esports scholarship offer, Champlin notes. “To a school in California I was actually given an athletic scholarship—same as basketball, lacrosse, football,” he maintains. “I was regarded as an athlete for esports, which is absolutely crazy!”

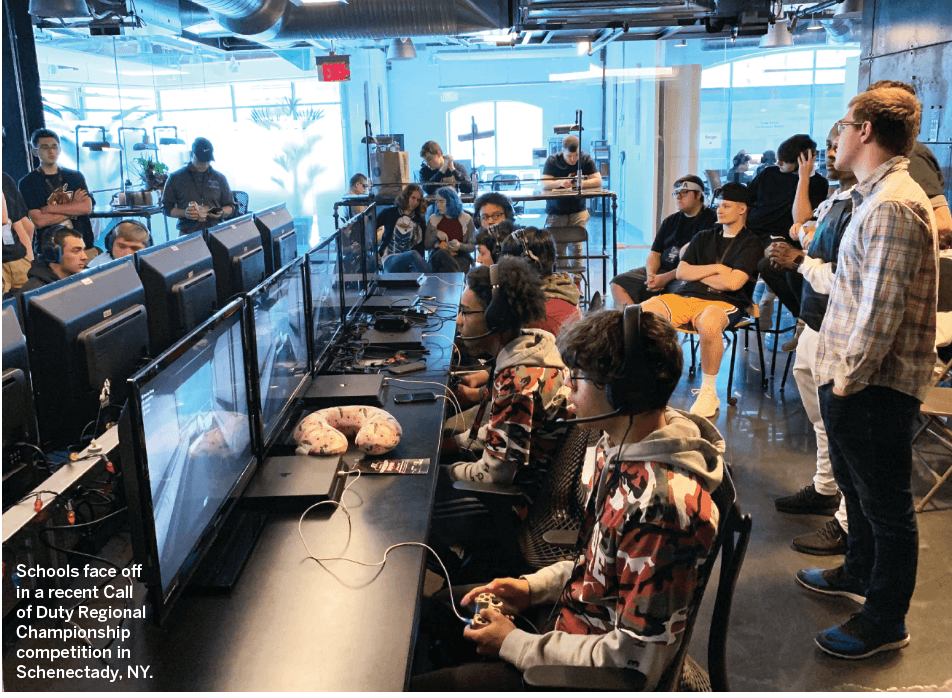

More than 160 club members participate in sanctioned competition, but many others drop into the club facilities simply to play games. Sponsorships have financed a fully equipped gaming arena where team members play side-by-side and face off against opponents across the room. “That makes it more like a sports event that’s easier for adults to grasp,” Champlin says of the face-to-face encounters.