Theta: Money for Nothing

Ready to make a profit just by letting time pass? With “theta,” it’s a distinct possibility

Imagine making money just by letting time go by. Savings accounts accomplish that but they’re about as exciting and profitable as watching paint dry. Luckily, there’s another way, and it’s called “theta.”

Traditionally, the only way to try to make money with stock is to buy it and wait until the price goes up. But what if there were a way to make money even if the stock doesn’t budge? In the world of options, that’s possible because of the powerful concept of theta.

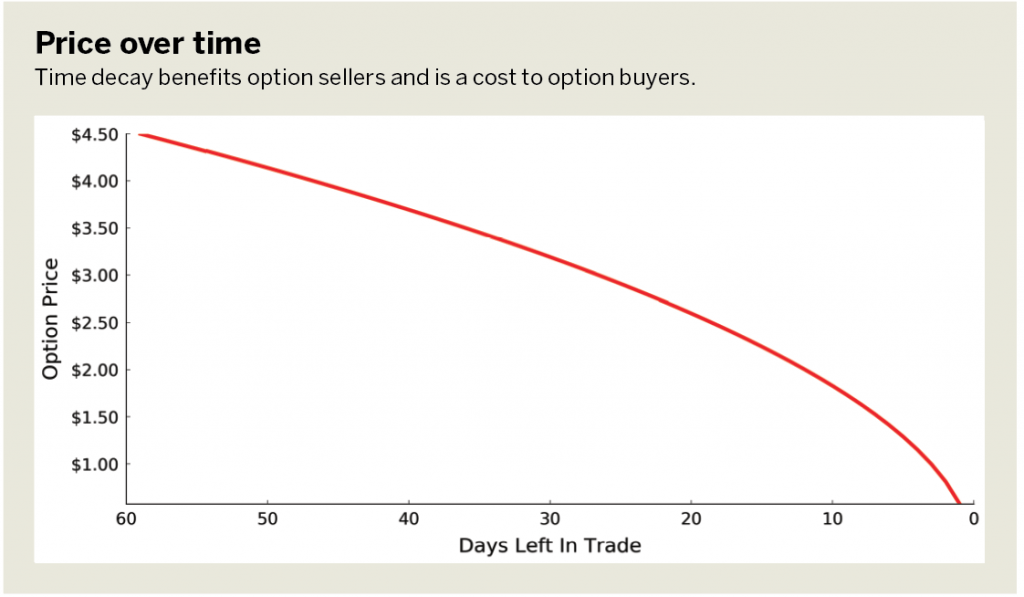

Theta is a number that represents a phenomenon that occurs with all option contracts: time decay. Options’ values get whittled down over time, all the time. And by selling options, investors take advantage of that time decay.

Every time a trader sells an option, a positive theta value is associated with his position. That means that every day that passes, all else remaining equal, the price of the option decays by the theta value, and the seller has generated a profit on the position.

Time decay benefits option sellers and is a cost to option buyers. Why? Think about options as insurance contracts. When an insurance company sells an insurance contract, the company collects monthly premiums from the insurance buyer. In exchange, the company takes on the risk for the value of whatever’s insured. The same is true with options, both short calls

In exchange for taking on that risk, the seller is entitled to a daily premium, aka positive theta.

So, what affects the value of theta? In other words, what determines the amount that the option seller will collect each day the stock doesn’t move? Three main factors come into play: the price of the underlying stock, the time until the option expires and the stock’s level of implied volatility (uncertainty).

The price of the stock affects the theta value because the more expensive the stock is, the larger the prices of options and thus the larger the amount of theta. Think of it as selling insurance for a mansion as opposed to a shack. Both have risk, but the mansion (high-priced stock) has more risk than the shack (low-priced stock).

Next, the time until expiration is inversely related to the value of an option’s time decay (theta). Generally, as an option approaches expiration, the theta value increases. When an option is far from expiration, the theta value is small.

Finally, the level of implied volatility (uncertainty) and theta are directly related. When implied volatility goes up, so does the option’s daily premium decay. Think of this as buying hurricane insurance for a condo in Florida versus a condo in the landlocked Midwest. Obviously, hurricane insurance is a lot cheaper in the Midwest because there’s very little risk of a hurricane in Iowa. In Florida, on the other hand, there’s a lot of risk of a hurricane and, therefore, the insurance premiums will be more expensive.

It may be becoming clear why it’s possible to make money on a stock that doesn’t budge. By selling premium and collecting theta, the stock does not have to move. This is similar to the way insurance companies make money in the long term. Most of the time, hurricanes aren’t hitting the condo, but the company continues to collect the premium. On occasion, a hurricane does hit, and the insurance company has to pay—but most of the time that doen’t happen.

So, each individual investor must decide whether to buy or collect the premium. Neither is necessarily a “better” strategy, but one has better probabilities by collecting theta. Selling premium can be daunting at first, but in the long run, with a consistent strategy and the patience to let the probabilities work themselves out, theta will become a new friend.

Anton Kulikov is a trader, data scientist and research analyst at tastytrade.