Volatility Risk: It’s All About the Vega

When implied volatility moves up and down a lot, as it has been in recent months, many traders and investors become more attuned to their portfolio’s exposure to vega.

For those seeking to reduce their exposure to vega, a couple easy choices include closing open positions with high vega, or reducing them, as well as deploying fewer new positions with high vega.

Alternatively, traders may instead decide to adjust the scale of the positions they are deploying, and utilize trades with inherently less vega risk.

Vega is the Greek that reports how the value of an option changes with increases or decreases in implied volatility. In this regard, vega helps traders understand how sensitive a position, or their portfolio, is to changes in the “speed of the market.”

When increasing market velocity pushes implied volatility higher, one’s portfolio profit and loss (P/L) can also fluctuate to a higher degree than “normal” due to vega exposure.

In turbulent times such as this, some traders and investors may elect to reduce their vega exposure, while others may seek to increase it (depending on their outlook and approach).

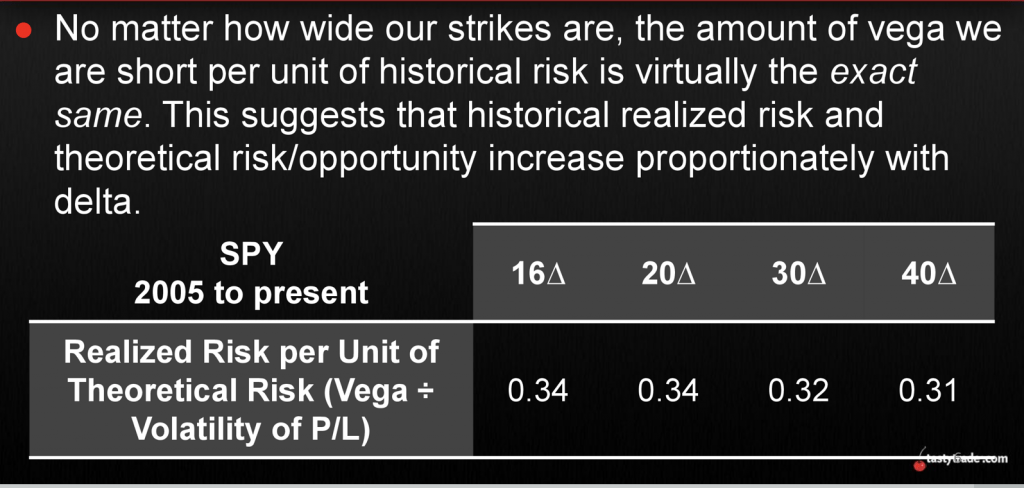

According to research conducted by tastytrade, vega risk does remain relatively efficient, whether one deploys low vega or high vega positions (or anything in the middle).

In essence, that means taking on additional potential reward using higher vega positions, directly translates to a proportional increase in the potential risk – and almost perfectly so. Vice versa, that also means taking on reduced vega risk, while lowering potential reward, still offers a high utility potential for profit from movement up or down in implied volatility.

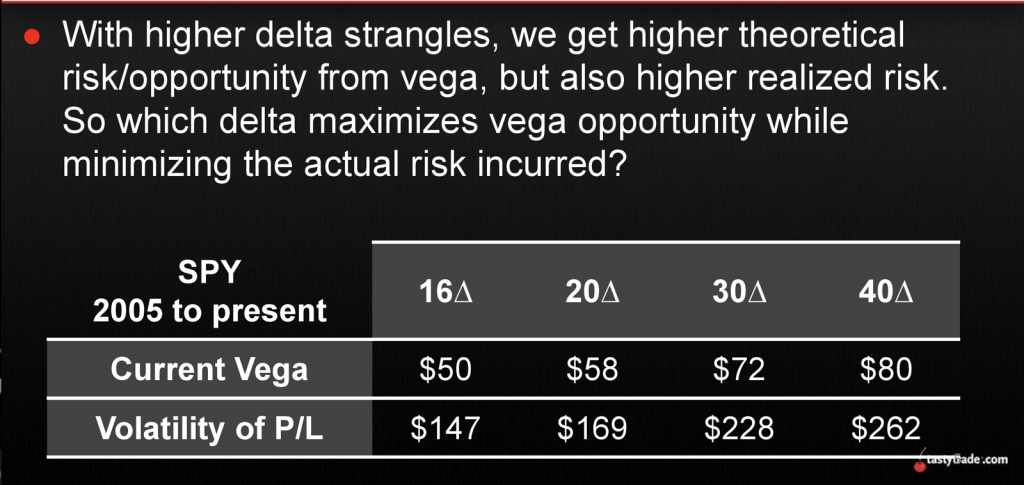

This dimension of vega risk is illustrated in the two graphics below, which summarize tastytrade’s findings:

As one can see in the first graphic above, the potential volatility of the P/L of a given position increases in linear fashion as more vega risk is taken on (i.e. higher delta strangles). Logically, the above makes sense, as positions with more vega should be more sensitive to fluctuations in implied volatility, which is represented by volatility in the P/L.

Building on that, the second slide above indicates that utility of vega risk remains proportional, no matter the delta of the strangle or straddle. That means the risk/reward paradigm is efficient and consistent, such that lower risk positions equate to lower potential reward, but proportionally so; for example, there isn’t a big dropoff in utility when reducing vega.

As a reminder, vega is defined in the options trading world as “the measurement of an option’s sensitivity to the changes in the volatility of the underlying asset.” Vega is one of the famous “Greeks” used in options analysis, but it is the only one not represented by an actual Greek letter.

Vega is typically expressed as the amount of money an option’s value will gain or lose as volatility rises or falls by 1%.

For example, imagine a hypothetical put in the SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust (SPY) has a vega of 0.20. That means that if the VIX goes up by 1, the value of that option should theoretically increase by $0.20. Reciprocally, if the VIX drops by 1, the value of that same option should theoretically decrease by $0.20.

Owned options (i.e. long options), whether they be calls or puts, therefore benefit from rising implied volatility, whereas short options benefit from declining implied volatility, which is the vega component of profitability.

It should be noted that options with longer dated maturities will have a higher vegas than closer-dated maturities. Additionally, vega is higher for at-the-money options as compared to out-of-the-money options.

The latter point speaks to why higher delta strangles (and straddles) have more vega exposure than lower delta strangles.

Due to the importance of vega when trading options and volatility, readers may want to utilize these additional tastytrade resources on the subject when scheduling allows:

- Mike and His Whiteboard: Option Greeks, Vega

- Market Measures: How Efficient is Vega Risk?

- Best Practices: Vega Over Time

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.