Well, There Are Earnings Recessions and Then There Are “Real” Recessions

An earnings recession is generally defined as a period in which corporate earnings growth declines over two consecutive quarters.

Based on projections for the Q4 earnings season, which kicked off in strength during the week of Jan. 13, an earnings recession will have officially started when reporting for this quarter is complete.

Aside from underscoring the fact that corporate profits are shrinking, earnings recessions don’t necessarily suggest impending Armageddon in the underlying economy, or even the stock market.

Earnings recessions were observed in 2012 (two consecutive quarters) as well as in 2015-2016 (six consecutive quarters), and during those two periods, history illustrates that both the economy and equity markets held up rather well.

During calendar year 2012, the S&P 500 rose 14%, and from the start of 2015 to the end of 2016, the S&P 500 rose about 12%. While the latter period of 2015-2016 was slightly weaker in terms of performance, neither period demonstrated the type of extended panic that would compel a market prognosticator to “cry wolf” regarding a future earnings recession.

For reference, the average annualized total return in the S&P 500 over the last 90 years is approximately 9.8%, although one has to consider that the last several years have skewed that number a bit higher (the S&P 500 is up over 1,200 points since the start of 2014).

While the most recent earnings recessions weren’t that tough on the economy or the stock markets, the last “real” recession was basically a disaster for both.

A recession in the real underlying economy is typically defined as two consecutive quarters in which Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracts. The last real recession observed in the United States was the “Great Recession,” which lasted from December 2007 until June 2009.

With a length of 18 months, the Great Recession was considerably longer than the average historical recession in the U.S., which is about 10 months. Had the Great Recession lasted any longer, it would have qualified as a “depression,” which is basically an extended recession (three years or more), or a period in which GDP pulls back by 10%.

As most are already aware, stock market performance during the Great Recession was horrific.

From the highs in the S&P 500 observed before the start of the Great Recession to the lows visited during the height of the panic, the S&P 500 essentially lost 40% of its value. GDP during this time fell about 4.3% from peak to trough, which helps underscore the severity of the crisis.

Obviously, the Great Recession was also accompanied by an earnings recession. With the economy in severe contraction, corporate profits were shrinking, and losses were widespread.

Based on the above data and information, one can extrapolate that earnings recessions on their own don’t appear to signal an upcoming decline in equity prices, at least according to recent history. On the other hand, when an earnings recession has occurred in the midst of a “real” recession, historical data illustrates that the real economy, as well as asset prices, were severely impaired.

Fast forwarding to the present, many might recall that 2019 was filled with fear that a real recession might be on the horizon. The U.S.-China trade war was raging, and global economic growth was anemic. China’s economy did, in fact, contract in 2019, when GDP growth dropped from 6.6% in 2018 to 6.3% in 2019. China’s economy is expected to grow at an even slower pace in 2020.

The United States, on the other hand, has so far avoided a technical recession.

GDP growth for the second and third quarters of 2019 were both above 2%. Likewise, job creation in the United States remained relatively constant throughout last year. However, there are signs that the U.S. economy may still be walking a fine line in terms of potential risks to the downside.

It was reported at the start of 2020 that manufacturing activity in the United States recently hit a 10-year low.

The Institute for Supply Management (ISM) reported on Jan. 3 that the U.S. manufacturing index dropped to 47.2 in December. That’s the lowest reading in that gauge since June 2009, when it was as low as 46.3. Any reading below 50 is perceived as a contraction in activity, and December marked the fifth straight month of readings below that critical level.

Combining this information with the fact that an earnings recession is expected to officially start at the end of this reporting season, one might reasonably wonder just how strong the underlying economy currently is in the United States.

On top of the earnings dynamic, it should be further noted that according to certain metrics the U.S. stock market is currently “overvalued.” Today, the price to earnings ratio for the S&P 500 on a forward basis is 19.3. The historical average of that metric is closer to 15-16, which means that earnings growth is deteriorating at a time when stock prices appear to be factoring in the opposite.

It’s possible the recent signing of the Phase 1 trade agreement has most investors feeling optimistic that global growth is set for a rebound. If that is the case, it’s likely that corporate earnings growth will improve in Q1 and Q2 of 2020.

However, if the Phase 1 deal fails to deliver on the promise of a return to “normalcy” in global trade and productivity, then the likelihood of a contraction in the underlying economy without question goes up. Under that scenario, it’s difficult to see how stock prices could maintain their current expensive levels.

Consequently, traders should be extra vigilant during the start of 2020 and monitor ongoing earnings guidance, as well as indicators for the U.S. economy, extremely closely.

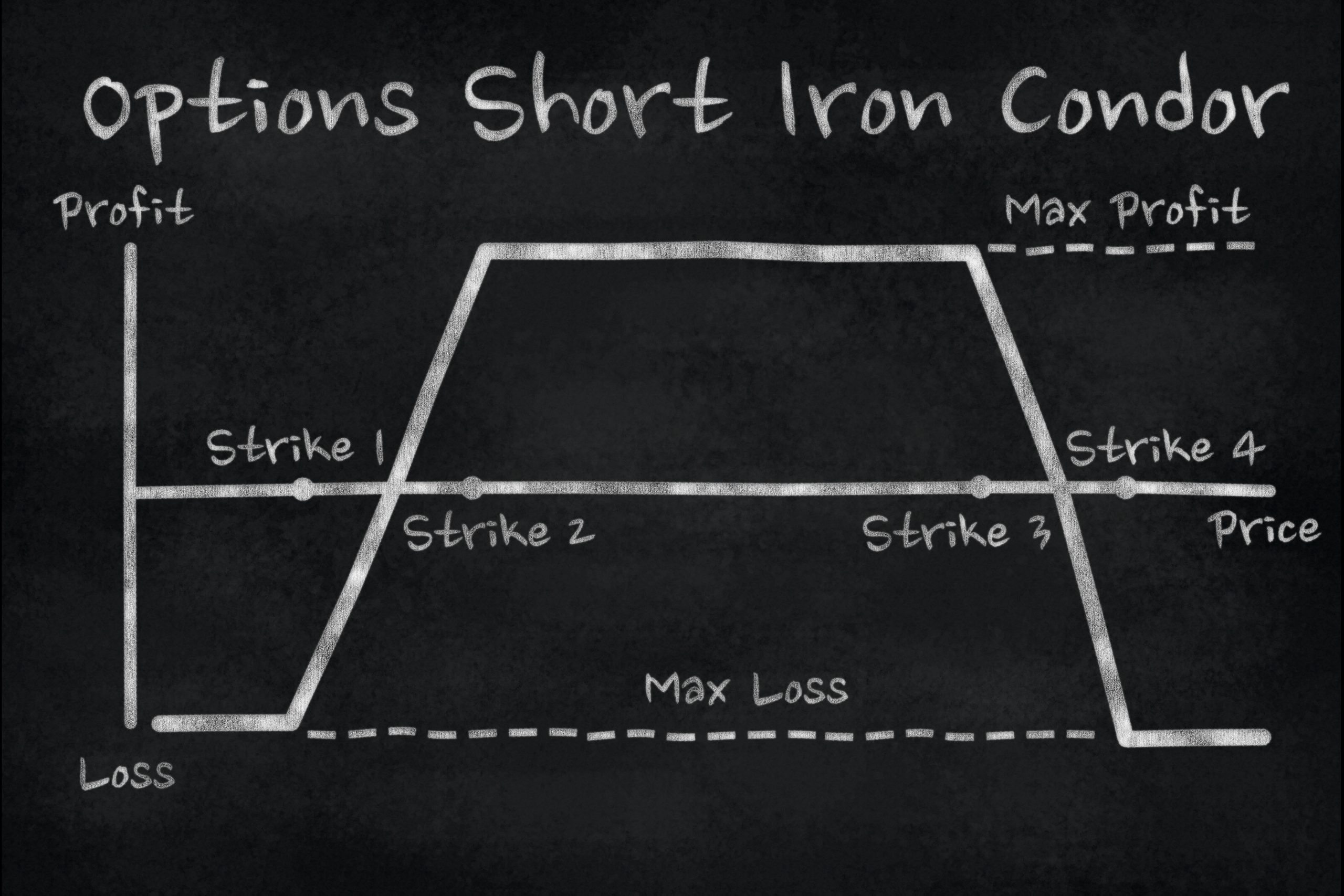

The last time a real recession accompanied an earnings recession, global financial markets saw an incredible surge in volatility.

While past performance does not predict future outcomes, one would think that a redo of 2007-2009 (earnings recession combined with real recession) would result in at least a marginal increase in volatility. The VIX is currently trading at 12 and change, and one can’t forget there’s also a big election slated for November.

To learn more about trading corporate earnings announcements, traders are encouraged to review a previous installment of Best Practices: Earnings Mechanics when scheduling allows.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.