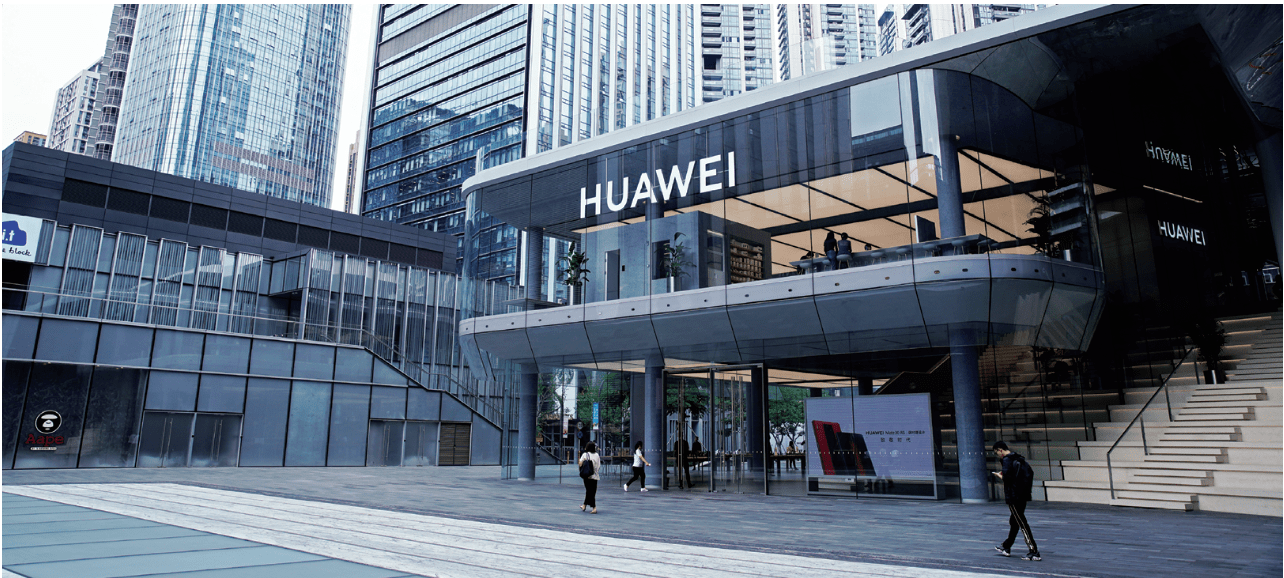

Huawei, 5G & the US-China Tech War

Is the West ceding power to China?

Most countries have a city or region that’s the national leader in technological innovation and development. In the United States, it’s California’s Silicon Valley, and in India it’s the city of Bangalore.

In China it’s the city of Shenzhen, which is arguably the fastest-growing major city in the history of humanity and is located a 20-minute, high-speed train ride from the center of Hong Kong.

Today, the Shenzhen prefecture occupies roughly 675 square miles of land north of the Hong Kong border. Shenzhen presents stark contrasts—it’s China’s richest city but workers sweep the streets with straw brooms and make as little as $300 a month.

One could argue Shenzhen is one of the most...