The Dragon that Stalks the West

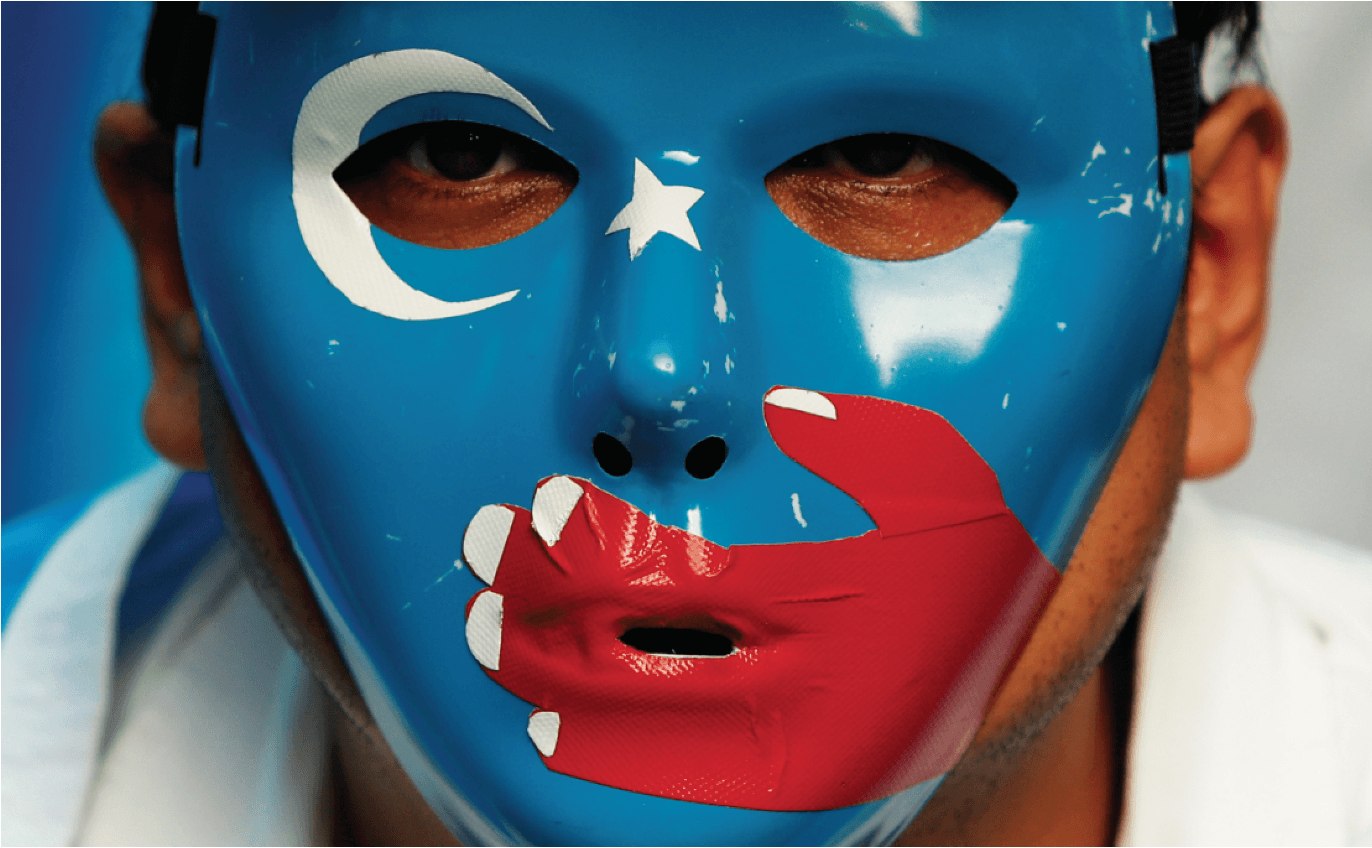

As democracies look the other way, China is exporting the surveillance, censorship, social control and genocide it perpetrates within its own borders

An activity as mundane as an English class can arouse the suspicion of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). That’s why the authorities routinely show up in classrooms to check students’ ID cards. Almost invariably, nothing’s amiss—but on a recent school visit police encountered something unexpected. An American researcher was sitting in on the lesson.

The American feared the worst when he realized he’d left his passport at the hotel. But not to worry—a Chinese police officer already had the situation under control. He punched the foreign visitor’s name into a handheld device that immediately displayed his passport number, hotel reservation and who knows what other private, personal, sensitive information.

It wasn’t an isolated incident. The People’s Republic of China is spinning a spider’s web of surveillance, censorship and authoritarianism to monitor and control a growing portion of its citizenry and its guests from other nations. The horror doesn’t stop at the borders because the CCP and its puppet corporations are exporting those evils to other dictatorships and even to democracies. It amounts to an undeclared cold war.

Asserting more authority

Arguably, China’s current push toward perfecting totalitarianism turned more serious in 2017 with the suppression of the Uyghurs, a Muslim ethnic minority targeted for assimilation into mainstream China. (Click here to read “Sino-Muslim Horror.“)

The Uyghurs live under nearly constant scrutiny by the CCP, whose operatives employ long-established tools of social control, such as ID cards, checkpoints, interrogation, resettlement, torture, rape and murder. They combine those time-tested means of coercion with newer methods of intrusion that rely on video cameras, facial recognition, DNA samples, voice recognition and artificial intelligence.

The CCP is using that integrated arsenal of low- and high-tech tools to reign in the freedom of a growing list of groups in China, says Sarah Cook, a senior research analyst at Freedom House, a New York-based democracy watchdog. After the suppression of Uyghurs came the harassment of suspected drug addicts, former criminals, banned religious groups—such as Christians and Buddhists—and foreigners of every stripe, Cook notes.

Compiling a DNA database of minority groups amounts to a latter-day version of the punch cards the Nazis used to track Jews in Germany, according to Sophal Ear, professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College in Los Angeles. For him, the injustice minorities suffer in China brings to mind the ravages the Khmer Rouge inflicted in attempts at social engineering in his native Cambodia.

Besides all-encompassing surveillance, China pursues social engineering by employing iron-clad censorship of ideas that conflict with the dictatorship’s goals, says Hong Kong-based James Griffiths, author of The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet. “The party realized pretty early on the danger of technology could pose in the form of encouraging dissidents,” he says. “They started baking in controls and propaganda.”

The government and companies such as Weibo and WeChat collectively take online action that constitutes part of the Great Firewall, Griffiths continues. The combined entity inspects internet traffic entering or leaving China and blocks anything deemed objectionable, he says. It began as little more than a porn filter but added sophisticated artificial intelligence and tens of thousands of human censors, growing into a key means of controlling China’s citizens, he contends.

It’s also one of many tools that ensures the CCP’s s power over the Chinese people doesn’t slip away even when the country’s students, businesspeople, diplomats and refugees are living abroad, Ear suggests. Relentless monitoring also makes sure expatriates know that anything they do in any country can result in reprisals against friends and family members who have remained behind in China. Cook adds that researchers have found that 70% of Chinese students attending U.S. colleges and universities practice a cautious self-censorship. Griffiths says of students that “they are going abroad and kind of taking the Great Firewall with them on their phones.”

Exporting misery

But the Chinese aren’t alone in feeling the pain of the authoritarian practices that have arisen in their country, according to multiple sources. The Chinese government owns controlling interest in several companies—like Hikvision—that produce some of the world’s best surveillance hardware and software. By selling that equipment abroad, the CCP can profit financially and simultaneously spread tyranny, says Griffiths. “We’ve seen various places like Vietnam adopt a cyber security law which is very, very similar to China’s own, and it comes after multiple meetings with officials in Beijing,” he notes.

The resulting dependence on China for surveillance merchandise and surveillance training typifies the one-sided trade relationships China is forging to solidify its power around the world. When a country relies on commerce with China, its governments and businesspeople begin to practice self-censorship in the face of Chinese atrocities.

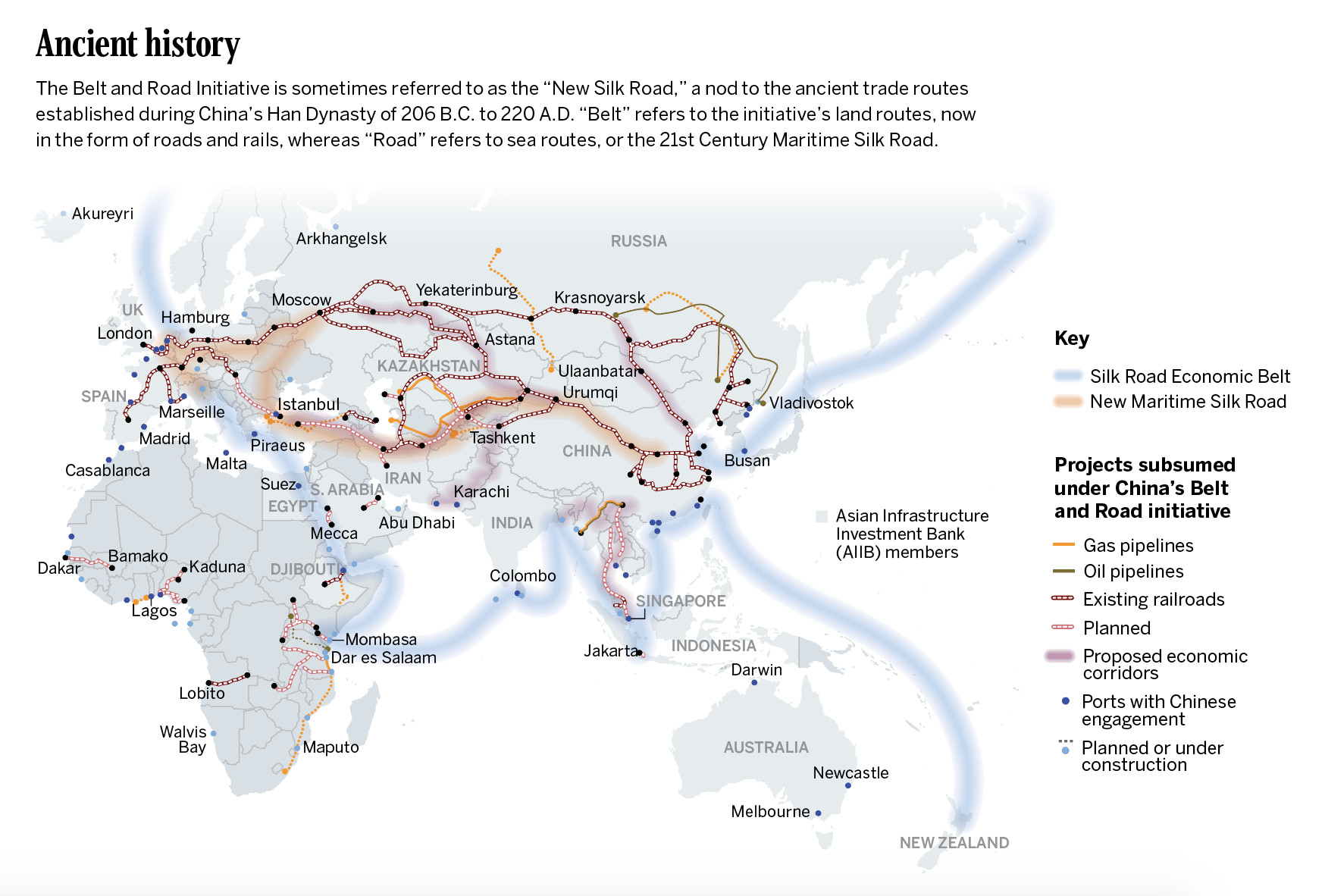

It may not come as a shock that trade-related fears can make dictatorships in poor countries turn a blind eye toward China’s evils. China wields economic power in the Third World by developing infrastructure that also serves strategic military goals for China, says Ear. Besides the need for funding, authoritarians might even feel a kinship with China and its harsh policies, he says.

But Western institutions fall victim to China’s temptations, too.

For many businesses, the sheer size of the Chinese market can prove too much to ignore. Management learns to keep quiet because China displays almost zero tolerance for dissent, contradiction or criticism. Why make a movie that won’t be shown on China’s screens? Why miss out on revenue from China’s NBA fans?

Strong-arm tactics

China’s not above flexing some muscle to get its way—even when it comes to policy-making in the United States. It didn’t work in 2012 when a Chinese diplomat journeyed from the consulate in San Francisco to convince the mayor of Corvallis, Ore., to force a merchant to remove an outdoor mural that advocated independence from China for Tibet and Taiwan, Cook says. But in 2017 the California legislature shelved a resolution condemning China’s persecution of the Falun Gong spiritual movement after receiving a letter from the Chinese consulate warning that the measure could harm relations, she notes.

China sometimes steps beyond writing cautionary letters and instead takes retaliatory action that carries financial repercussions for investors, Cook continues. In 2012, when the New York Times published an unfavorable article on the family of China’s prime minister, China blocked its citizens’ access to the newspaper’s English-language website and its brand-new Chinese-language site. The paper’s stock declined 20% and recovered only slowly and its sales staff had to renegotiate advertising contracts because of the loss of readership, she says.

The United Nations also provides China with a means of asserting power. As one of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, China wields veto power over many of the body’s resolutions. Meanwhile, China being China, it simply packs the clout to influence much of what happens at the U.N., Cook asserts. It also doesn’t hurt that China makes the second-largest financial contribution—after the U.S.—to operating the U.N. last year, she adds.

Masking inner weakness

The CCP’s desperate need to appear economically successful has led the National Bureau of Statistics of China to employ sketchy accounting practices that inflate sales volume for Chinese companies. (Click here to read “Chinese stocks: Caveat emptor.”)

But such antics, even when backed by the CCP’s awesome displays of power, can never disguise the fragility at the heart of the dictatorship, Cook asserts. Dissent inevitably arises, she says, noting the example of police offer who can’t avoid becoming friends with a religious leader he’s supposed to monitor and suppress. There’d be no need for propaganda and censorship to prop up a government that the populace supports, she says.

Luckbox readers should avoid the whole mess, Cook urges. “The real danger is complicity,” she maintains. “If you’re investing in Tencent, you’re complicit in innocent people being put into jail. People get killed because of information collected by these tech companies.”

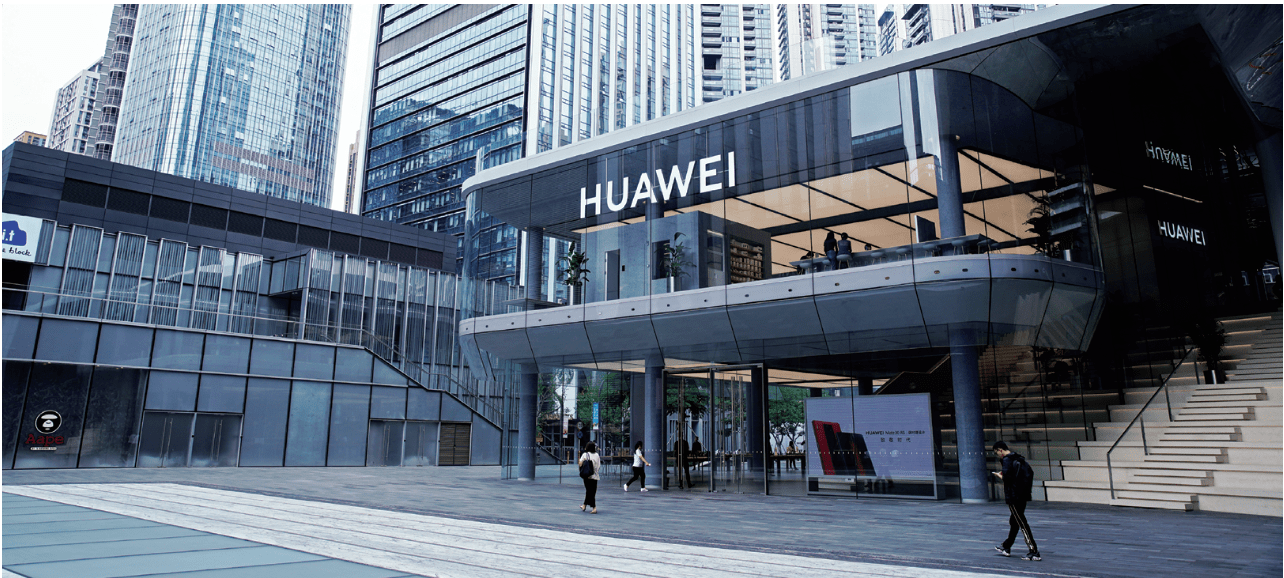

Inviting the CCP to come in from the cold won’t turn out well, Cook warns, providing the example of Chinese-made communications technology. “5G is a backdoor into our personal information,” she says. “Once (China) has that access, it’s only a matter of time before it’s detrimental to our civil liberties.”

The cancer of surveillance and censorship spreads from China to other countries that are emboldened to adopt the Chinese model in part or in full, warns Griffiths. What’s more, the compromises companies make to operate in China don’t stay in China. After Google built Dragonfly—a censored search engine—for China, other authoritarian regimes wanted their own versions, he notes.

Ear sums up the situation this way: “It’s sobering. America needs to wake up to the dangers. Is it worth selling your soul by shutting your mouth when see something?”

Social Score: 1984

It’s no use monitoring the citizenry unless the resulting data serves some purpose. To that end, China is testing a Social Credit System that yields scores for good and bad behavior.

Infractions that could lower a score and result in punishment include anything and everything from jaywalking or running a red light to eating on rapid transit or failing to show up for a restaurant reservation. In one example, anyone caught on camera failing to pick up after a dog could lose the right to own a pet.

Chinese earn credits for good deeds, such as donating blood, giving to charity or volunteering for community service. They can offset the negatives accrued through misbehavior or wrongdoing, and it’s all considered official because artificial intelligence juggles the merits and demerits.

China’s government is trying out variations on the system in different parts of the country and appears nearly ready to go national with a uniform approach. It could even rule the behavior of Chinese nationals when they’re abroad.

Critics complain that China’s system of Social Credits possess dark, unprecedented power to control nearly every aspect of life, signaling the end of privacy, dignity, dissent and personal initiative.

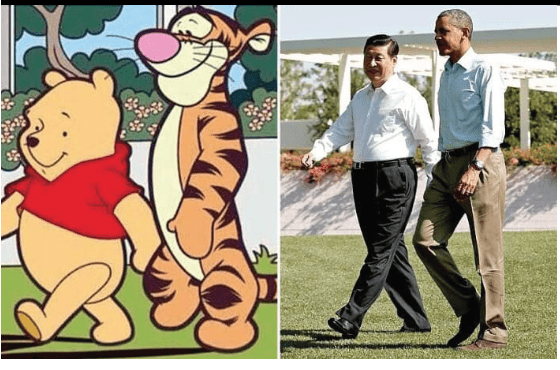

Don’t Poke the (Pooh) Bear

A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh, a seemingly unlikely candidate for censorship, was nonetheless banned in China following internet memes likening Chinese President Xi Jinping’s physique to that of the lovable, honey-eating bear. While the memes date back as far as 2013, when President Barack Obama was photographed walking alongside the Chinese leader at the Annenberg Retreat at Sunnylands in Rancho Mirage, Calif., the ban is believed to have been enacted officially in mid-2017. But just how strong is the embargo on the bear? Apparently stringent enough to interfere with the release of the 2018 live-action film Christopher Robin.

“Band in China”

The creators of South Park love pushing boundaries and provoking controversy. Yet they produced the show for more than 20 years before it was banned in China. The Chinese Communist Party finally took offense to Episode 299, aptly titled “Band in China.” It came out in October and not only criticized the Chinese government for censorship but also the American entertainment industry for appeasing Chinese censors. After word of the ban reached South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker, the duo issued a second jab in the form of a fake apology that said in part: “Like the NBA, we welcome the Chinese censors into our homes and into our hearts. We too love money more than freedom and democracy.”

Nothing to See Here

Under the iron fist of the Chinese Communist Party, it’s easier to list what isn’t banned than what is. Just the same, here’s a (very) partial list of what the CCP has outlawed.

Books: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Green Eggs and Ham, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover

Websites: YouTube, Facebook, Google (including Maps, Docs, Drives, Sites and Picasa), Twitter, Dropbox, Foursquare and Flickr

Movies: The Dark Knight, Back to the Future, Dead Pool, Avatar, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Ghostbusters, Star Wars, Noah, The Dark Knight and The Departed

Television shows: Doctor Who, Bojack Horseman, Peppa Pig and South Park