Chinese stocks: Caveat Emptor

Alibaba illustrates a Chinese scheme that attracts foreign capital

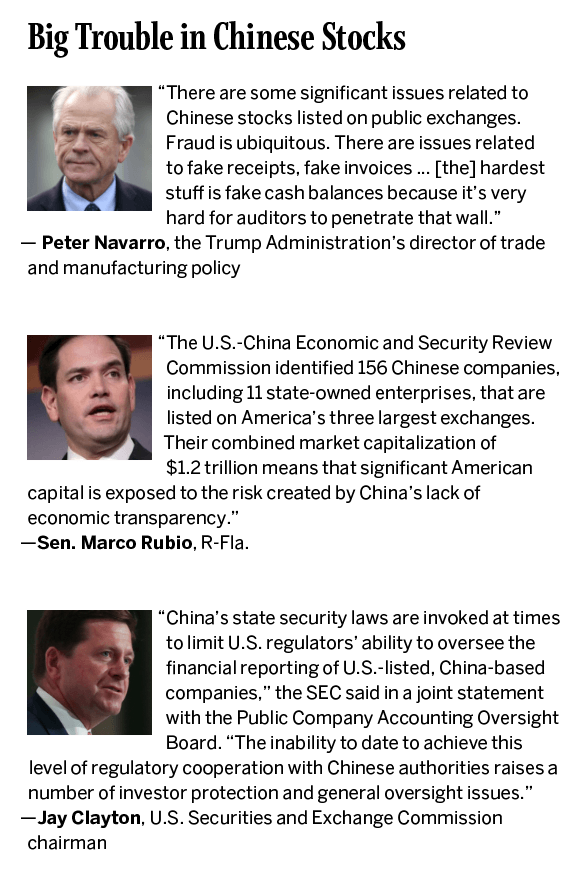

For more than a decade, the Chinese Communist Party has refused to allow America’s Public Company Accounting Oversight Board to examine audits of Chinese companies whose shares trade on the NYSE, Nasdaq and other U.S. exchanges. So Chinese companies have avoided oversight while raising billions of dollars in the U.S. Luckbox invited global macro strategist and forensic accountant Emma Muhleman to reveal how China has abused accounting standards and SEC regulations to take unfair advantage of American investors.

Americans who think they’re investing in Chinese tech giants are actually buying shares in offshore shell companies with no operations and no assets. The cash they pay for the worthless “stock” may actually go directly into the coffers of the Chinese Communist Party to fund oppression, surveillance and censorship.

Take the example of a typical American investor who thinks he just put some money into the Chinese E-commerce juggernaut Alibaba (BABA). He didn’t. Someone else in the U.S. might believe she picked up some stock in China’s Tencent (TCEHY) or Baidu (BIDU). Nope, didn’t happen.

Why are they being fooled? Two reasons. First, foreigners aren’t allowed to own shares in Chinese companies. Second, Chinese business people and government officials have figured out a scheme that attracts foreign capital in exchange for nothing at all.

The scam works well because Chinese companies have no qualms about shamelessly abusing accounting standards to overstate their sales volume and distort their financial reports. Importantly, it’s not a crime in China to defraud U.S. investors.

This results in a culture of dishonesty. Why the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) would allow companies like Alibaba to use this structure to list on the U.S. markets is indeed puzzling. It’s especially difficult to understand given China’s long history of plotting to procure hard currency outside its protectionist borders.

How does it all work? Let’s take look.

The mechanisms

The Variable-Interest Entity (VIE) structure, which is recognized by the United States Financial Accounting Standards Board, allows companies to list on American stock exchanges. They’re contractual agreements instead of direct ownership. Investors receive no right to share in profits and no authority to control the company.

In a reverse takeover (RTO), or reverse merger, a private company purchases control of a public shell company and merges it with the private company. Thus the private company avoids the complexity

and scrutiny of an initial public offering. This creates a loophole that has enabled a number of fictional Chinese companies to get traction in the U.S. and compete for American capital.

A wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) is set up in a place like the Cayman Islands or the Seychelles to take on 100% ownership of a VIE. The VIE holds the licenses and assets that enable operations in China, and the WFOE makes contracts with the VIE that purport to entitle it to the VIE’s operating profits in exchange for a “management” or “consulting” fee.

The contracts aren’t enforceable, and they’re illegal under Chinese law, but they’re designed to trigger “beneficial ownership” provisions in U.S. accounting standards, requiring the shell to consolidate the operations of the VIE in its SEC filings, giving investors the impression that it and the Chinese-owned VIE are the same.

Now, let’s look at how the alphabet soup of mechanisms work in practice.

Alibaba’s lack of magic

Alibaba Group Limited Inc., an entity incorporated in the Cayman Islands, trades on the New York Stock Exchange after raising $25 billion from Americans in its IPO, even though Chinese nationals and the CCP retain full control and effective ownership inside China. Just like magic.

The listing entity (Alibaba management) is not being transparent about what investors are buying. But the filing is virtually indistinguishable from others, misleading individual investors into believing the shares are worth something.

All of the hype aside, the company isn’t another Google or eBay. Its purported sales volume is wildly exaggerated. After all, the National Bureau of Statistics of China cooperates with the company to help inflate the numbers.

In an extreme example, Alibaba reports sales for Singles Day (the Chinese equivalent of Black Friday) in a manner entirely inconsistent with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). For example, Alibaba might offer a discount of $3 on a shirt that costs $5 and then record the entire $5 in gross merchandise volume.

Management could also pad its revenue reporting by including sales from real estate, defaulted airplane loans and utility bill payments made through its Alipay or Ant Financial partner. Meanwhile the company can tell the world that its mind-boggling (literally, impossible) results are a result of the healthy Chinese consumer markets.

And more trouble lies ahead. Alibaba’s management stressed on a recent earnings call that its margins will decline substantially as it spends “aggressively” on overseas partnerships and acquisitions. That suggests it has reached the extent of Chinese consumer growth.

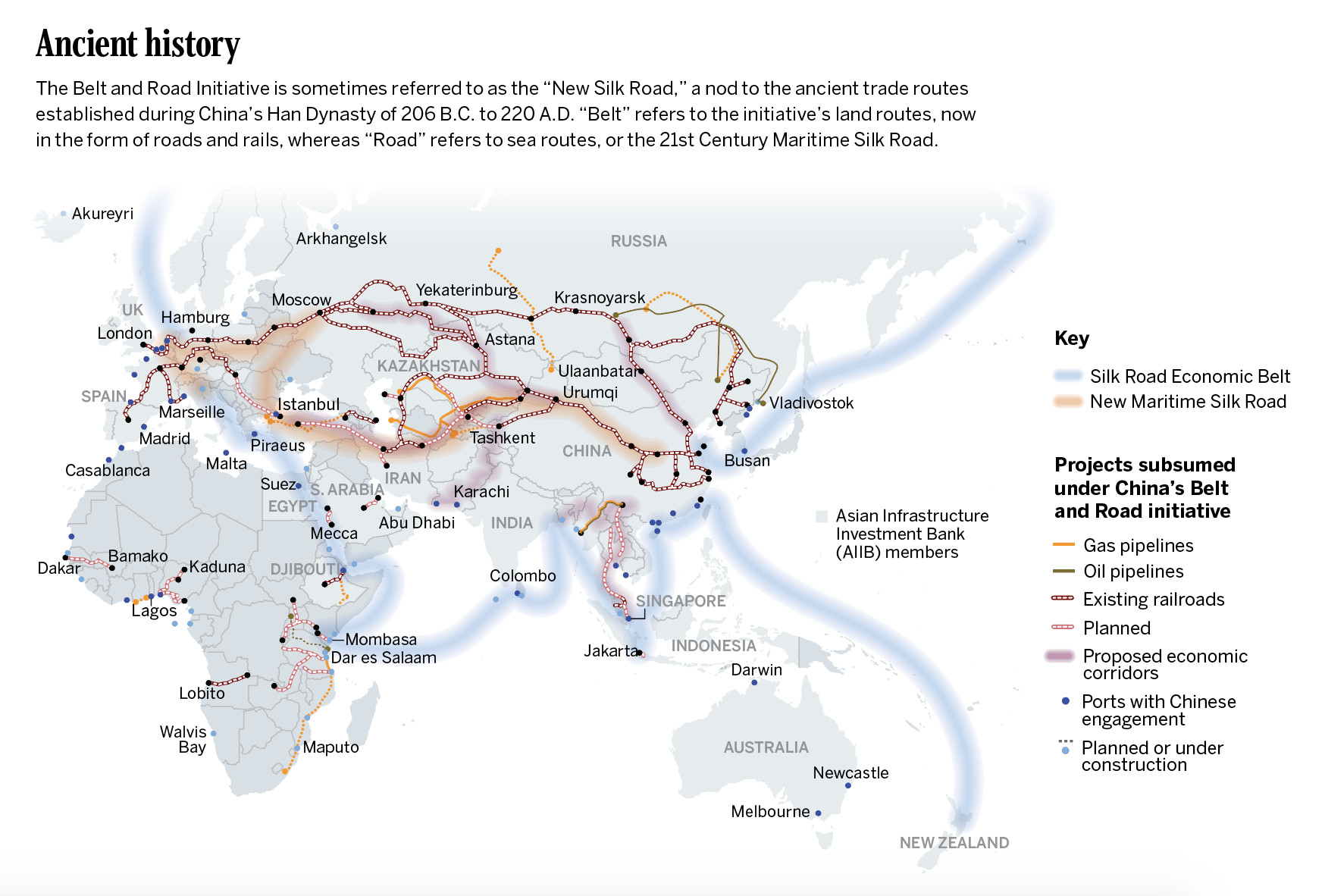

Still worse, Alibaba will face competition when it pursues its latest plan to offer payment services in Ethiopia. eBay already operates in the prominent developing economies.

Meanwhile, other problems are arising for Alibaba because its platform is used to sell counterfeit goods in the United States.

In response to the adversity, Alibaba cites its massive logistical operation, a creation supposedly capable of feats beyond human imagination given the number of workers it employs. However, with so much questionable or even blatantly false information emerging from the company, it would be understandable if observers questioned those claims.

Smaller scams

Though giants like Alibaba get most of the attention, tiny Chinese entities have also managed to exploit the same mechanisms, including reserve mergers.

The documentary The China Hustle (2017) shows how Roth Capital and another investment bank matched low-quality Chinese businesses to shell companies and then attracted an investment audience in the United States. Some of the companies have virtually no operations at all. They might, for instance, sell minor assets to family members to show big accounting gains.

The SEC had to deal with a flood of these bogus companies suddenly appearing on U.S. exchanges. Of 182 Chinese companies surveyed on the NYSE and Nasdaq, 125 (69%) use the VIE structure, according to Paul Gillis, professor of practice at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management.

When investors realized the WFOE shell companies were worthless, the share prices tanked and the Chinese Communist Party forced them to delist. But some of the empty companies survived and their shares are still offered today.

Ongoing need for cash

The discovery of fraud didn’t lessen the CCP’s need for regular infusions of capital. After rough times in 2015 and 2016, followed by an even more troubling period in 2018 and 2019, China’s reserves had been drained, according to an International Monetary Fund formula that suggests the bare minimum a country should maintain in what amounts to working capital.

That precarious position prompted the CCP to launch a frenzy of renationalization and to integrate the party into nearly every aspect of business, money and society, while monitoring internal discussion with heavy surveillance.

The party deemed some sectors “sensitive,” including E-commerce, media, telecom, internet, financial services and other “new economy” companies. Foreigners were banned from owning companies in those fields because that was now seen as a threat to the power of the state. And the state, in turn, relied on the capital markets to keep the whole thing spinning.

Inadvertently, the SEC regulations have contributed to the mess by requiring private companies that buy public companies consolidate their financial statements. The requirement obscured the histories of the firms and legitimized the presence of shell companies on the exchanges.

Discovering the scams

Because of the widespread use of the VIE structure, some institutional investors recognize it and don’t participate. Individuals seem more likely to get caught up in the subterfuge.

The CCP uses the scams to haul in much-needed foreign capital. The Chinese government’s prohibition on foreign ownership prevents foreign companies from wielding power and removing capital. For Alibaba management, the objective is to stay alive and use the schemes as the party requests. Clearly, companies in China operate primarily to serve the party, not the shareholders, employees, customers or the public in general.

In America, investors should be fully apprised of the pernicious ways U.S. citizens are duped, time and again, into funding the Chinese Communist Party’s ongoing, diabolical assault on human life.

Emma Muhleman, CFA, CPA, works as a long/short equity analyst specializing in forensic accounting at Ascend Investment Management, LLC. @emmamuhleman1