The New Silk Road

China’s Belt and Road Initiative is financing major development projects throughout the world. Is hegemony the goal?

When an economic superpower plans to invest trillions of dollars in other countries’ infrastructure in the name of regional connectivity and trade, one can’t help but wonder if its motivations are solely altruistic or if other factors are at play.

“We should foster a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation; and we should forge partnerships of dialogue with no confrontation and of friendship rather than alliance.”

Those words, delivered by Chinese President Xi Jinping during the opening ceremony of the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in 2017, underscore a popular narrative surrounding one of China’s most ambitious international projects.

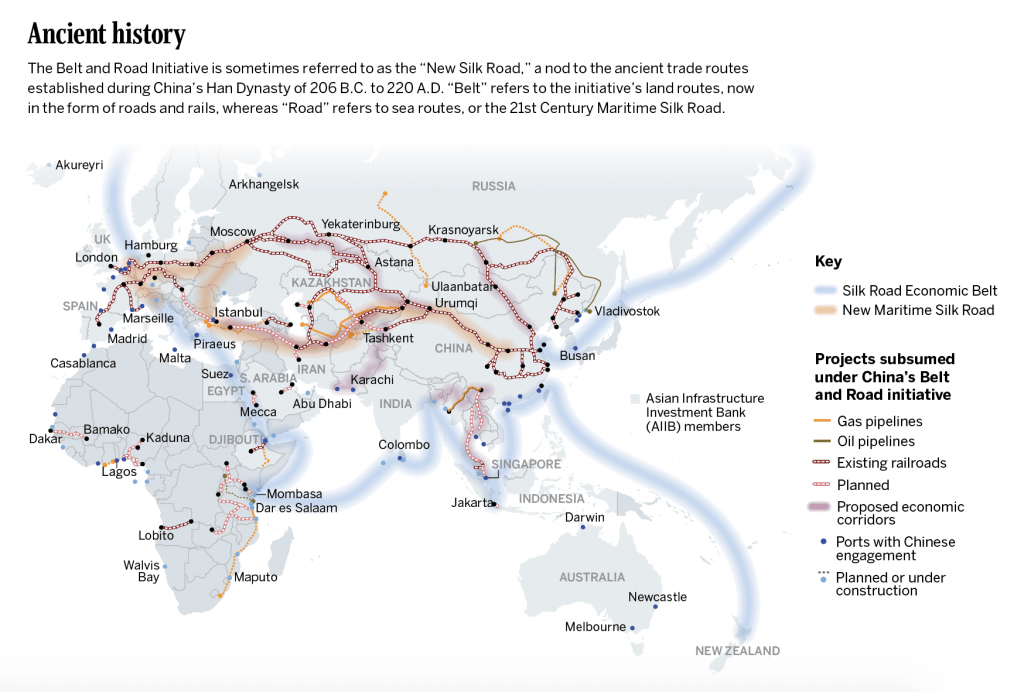

Originally called “One Belt, One Road,” China’s Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, is popularly understood as a large-scale trade, energy and infrastructure plan meant to “enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future,” in the words of the Chinese government.

Since it was announced in 2013,

the initiative has appeared in headlines that much of public disregards. The United States isn’t among the more than 60 countries where China has launched infrastructure projects, and it’s unlikely to become one anytime soon.

This begs the question: Should the American public care about the BRI?

“Yes, definitely,” says Nadège Rolland, a senior fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research in Washington. “And not just the American public, but everyone more generally because this has the potential to impact our world.”

Rolland has been researching the BRI since she began working for the nonprofit Asian policy think tank more than five years ago. She told Luckbox she was drawn to the subject because she wanted to understand for herself—straight from the source—what the architects of the BRI were thinking.

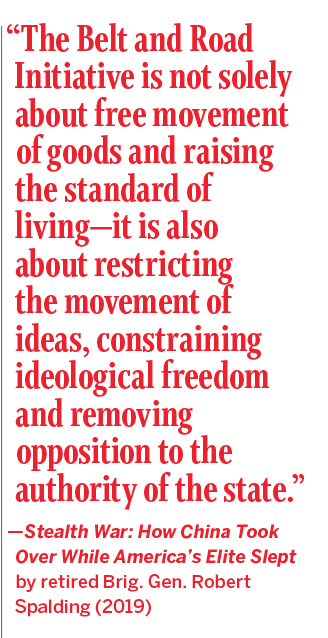

While infrastructure is a major component of the initiative, Rolland said less-talked-about layers include financial integration, unimpeded trade, strengthened political cooperation and people-to-people exchanges. To look at it only as an infrastructure-building project is superficial, she said. Instead, it’s a vision for a world with China at the helm.

“It’s sort of an inverted map of China versus American influence and power,” Rolland said. “Implicitly it says to the U.S. that China wants to have some sort of influence everywhere else in the world, therefore reducing the American influence and power on the rest of the world.”

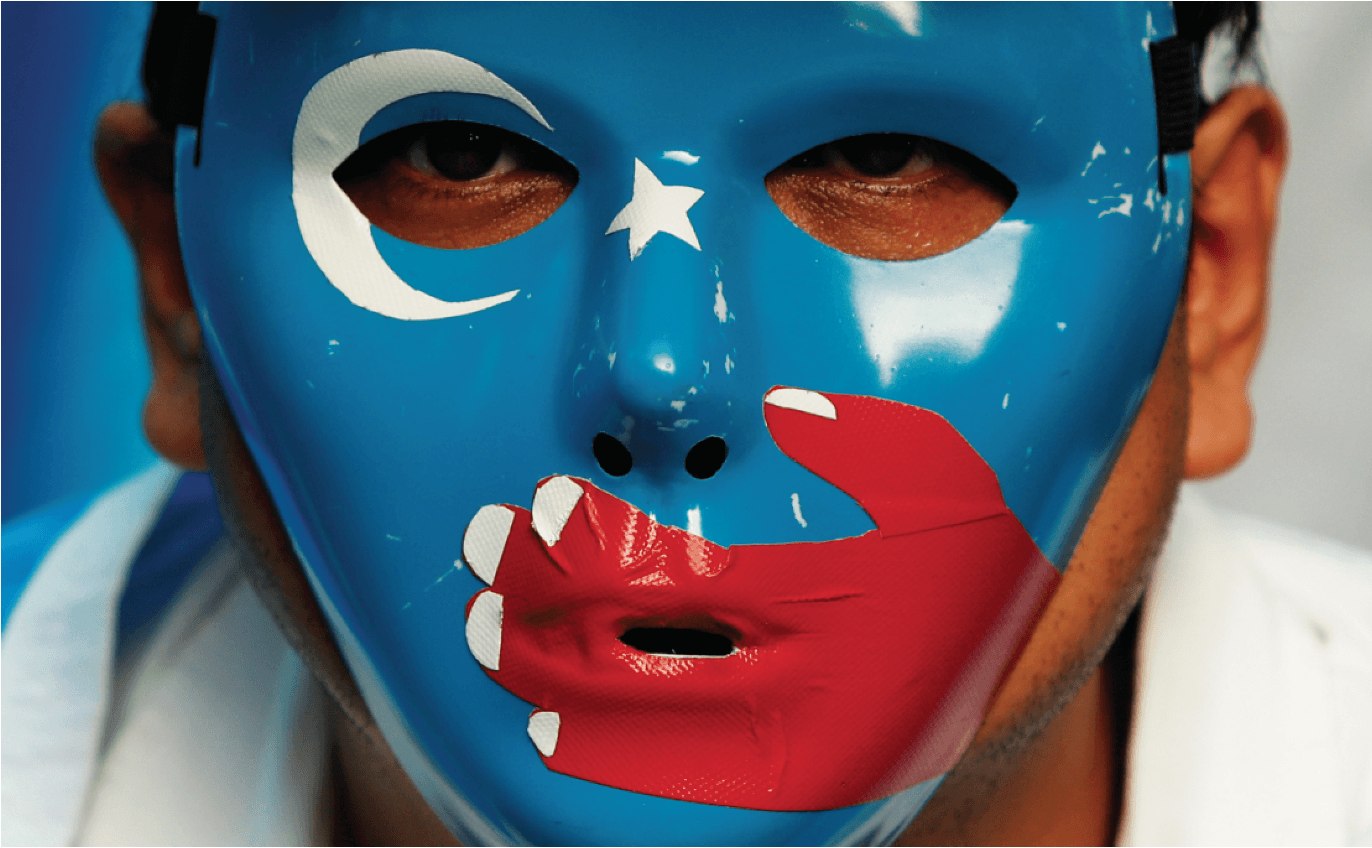

In retired U.S. Air Force Brig. Gen. Robert Spalding’s book, Stealth War, Rolland is quoted calling the BRI an “instrument of political warfare.” Political warfare, she said, is the use of all the instruments a state can muster, with the exception of military means, to achieve a geopolitical objective. That objective? Summoning support to grow China’s power and influence.

“We thought for a long time that democracy was the key to peace and prosperity,” Rolland said. “Beijing wants to demonstrate that you don’t need democracy to be prosperous and to be stable.”

But the BRI isn’t without challenges, not the least of which include navigating a storm of accusations that the initiative is a debt-trap diplomacy scheme, luring developing nations into borrowing money they can’t pay back. An often-cited example occurred in Sri Lanka, which in 2017 leased its second-largest port to China for 99 years in exchange for money to relieve debt owed to China.

While Rolland said she hasn’t found any indication in her research that debt-trap diplomacy is behind the BRI, 2018 research from the Center for Global Development concluded that “eight countries are at particular risk of debt distress based on an identified pipeline of project lending associated with BRI.”

Much remains unknown about the BRI and the long-term expectations it’s setting on the global stage, partly because information coming out of China is selective and opaque. Regardless, Rolland said the West should pay attention to China’s soft connections instead of just its physical or hard ones.

“I think many in the developing world really are welcoming and looking forward to partnering more closely with Beijing,” Rolland said. “In terms of impact this might have on the future world, I think we need to pay a lot of attention to that.”