The Pandemic, Immunity and the Long Game to Longevity

Living to a healthy old age is within reach but requires respect for scientific findings and adherence to good habits, according to a socially-distanced panel of Luckbox contributors

What can people do in the short term to boost their immune systems to resist COVID-19?

Aubrey de Grey: People would like to have some kind of quick fix or at least a quick partial fix. Unfortunately, what they can do right now with lifestyle, nutrition, supplements and so on is only going to have a very slight impact.

Jenna Macciochi: Yes, there’s no scientific way to truly boost your immune system except in the long term. I get what people mean—it’s a case of semantics over science. People want to feel like they’re invincible and they have an agency over their health, but your immune system is not an on-and-off switch. It’s more like a series of rheostats.

Dan Buettner: Even if we can’t improve immunity right away, self-isolating can provide a number of opportunities. Most of us are at home right now. According to Gallup, about 30% of us don’t like our jobs or aren’t using our strengths at our jobs. So, we know from both the health and the happiness points of view that getting the right job—since we spend most of our waking hours working—is constantly important. Taking this opportunity to reassess your job is not a bad idea.

Elaine Gavalas: Meditate while you self-isolate. Use the time to learn meditation and know all the benefits it’ll bring you. One of them, over time, is immunity. So you’re achieving a lot just by that simple thing, and that would be my prescription.

Michael Greger: After the pandemic, we can get back to longer-term improvements in health. The good news is we have tremendous power over our health destiny and longevity. The vast majority of premature deaths and most disability is preventable with a plant-based diet and other healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Turning to a more general question, life expectancy at birth has increased in the United States from 49 at the beginning of the 20th century to 78 today. What caused the increase?

an American explorer, National Geographic Fellow, journalist, producer and author, popularized the Blue Zones—five places where people live the longest, healthiest lives. His Blue Zone Projects organization works with municipalities, employers and insurance companies to introduce people to the beneficial health habits of Blue Zone residents. His books include The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the longest, Thrive: Finding Happiness the Blue Zones Way, The Blue Zones Solution: Eating and Living Like the World’s Healthiest People, and The Blue Zones of Happiness.

@danbuettner

Buettner: First and foremost, it was getting infectious disease under control and then the emergence of antibiotics and vaccines. But also public health has gotten a lot better—water sanitation and sewage. Those are the big ones.

Macciochi: I’d agree that the three big things are improving sanitation, vaccination and antibiotics. They’ve been the biggest step-function changes in our health in the last 100 years. That has eliminated the infections that would kill people in childhood and take people’s lives early.

Greger: A lot of that increase is due to decreases in infant mortality. But life expectancy at age five is more interesting from a chronic disease standpoint because you made it past those difficult first years. Life expectancy from age five hasn’t increased nearly so much as from birth.

de Grey: The best way to answer that question accurately is to divide the 20th century into two halves. The predominant cause of the increase between 1900 and 1950—and indeed starting before 1900—was a reduction in infant mortality as well as mortality not quite so early in life but still early. That occurred as a result of our increasing ability to stop people from dying of infections, such as tuberculosis and malaria. Back in the middle of the 19th century, more than one-third of babies would die before the age of one, even in the wealthiest countries

in the world.

The little things that go wrong at the level of molecules start really early in life, even before we’re born, and have an impact on our health throughout our lives. They essentially lay down damage that gets into a vicious cycle and causes an acceleration of the accumulation of subsequent damage. So the simple fact that in the early years of the 20th century economies in the industrialized world were becoming more prosperous—and therefore the general population was getting better nutrition—translated into progressively increasing life expectancy during the second half of the 20th century.

Life expectancy for men and women decreased in the U.S. from 78.9 years in 2014 to 78.6 years in 2017. Opioids, alcohol and suicide?

Buettner: Part of it was opioids but a larger part is the increasing rates of obesity, diabetes and dementia. Until we get those under control, you can’t expect to see life expectancy going up significantly, regardless of all the hype, genetic interventions, hormones and other gimmicks that marketers try to sell us. Diets, exercise programs, pills, supplements, drinks, bone broth, paleo and keto—none of it works for more than a few months.

Greger: Part of that is due to the opioid epidemic, but the No. 1 cause of death in the United States is the American diet, and it’s the leading cause of disability. It’s now bumping tobacco smoking to No. 2. Cigarettes now kill about a half million Americans every year, and what we eat kills thousands more. Most deaths are preventable and related to nutrition.

Will life expectancy continue to increase in the long run despite recent setbacks? If so, how much, and when might an increase occur?

Buettner: The best demographics suggest that the maximum average life expectancy of humans is probably in the lower 90s. So we’re hitting almost 80, but we’re probably losing a dozen or so years as a population because—

I argue, disruptively—that it’s our environment. Habits are notoriously difficult or even impossible to change on a population level. Whereas if you change people’s environment, you can get them to mindlessly change their behavior and the value proposition here is about a

dozen years.

Macciochi: A lot of the scientific data coming out now seems to show there isn’t a specific limit. It isn’t like once we get to 150 and that’s it. But we’re probably not going to find another big step-function change like we’ve seen with things such as improved sanitation, antibiotics and vaccines. Now we have this chronic disease problem—non-communicable diseases and non-infectious diseases that have a slow burn.

a British-born biomedical gerontologist, author and professor, has pioneered the field of rejuvenation biotechnology. He maintains that science will soon develop the means to repair the human body and that people will live longer as a result—perhaps for a thousand years. He’s a founder of the SENS Research Foundation, and his books include Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs That Could Reverse Aging

in Our Lifetime and

The Mitochondrial

Free Radical Theory

of Aging.

@aubreydegrey

de Grey: Within five years, enough evidence will emerge to convince even the skeptics that refurbishing the body is on the horizon. Within 20 years, there’s a 50-50 chance that materials and techniques will be widely available to reverse the health problems associated with aging. But we’re definitely not going to see any thousand-year-old people for at least another 900 years, whatever happens.

What’s the most important factor in increasing life expectancy — diet, exercise, immunity, scientific advances or something else?

Macciochi: We can’t make a hierarchy. All of them matter, and it’s the collective power of all of those that is going to be the biggest help to our lifespan. You can have the perfect diet, but if other aspects of your life are not serving you well and you’re very stressed or you’re feeling lonely or you don’t exercise, then the perfect diet is not going to do you much good. There are all these different levers that we have to pull and we’ll all have our own Achilles’ heel.

Greger: Sedentary lifestyles are leading contributors to years of healthy life lost. And so exercise is absolutely important. Not smoking—also absolutely important. But what we eat is the most important. The most critical decision we can make for ourselves and our families is what we eat three times a day.

Buettner: People in Blue Zones live longer than others but they don’t necessarily have more responsibility or pay more attention to better discipline or better diets. They just live their lives. It’s shocking how much people in Blue Zones are exactly like we are. They live a long time—not because of superior genes—but because they have an environment that promotes good habits, such as walking and avoiding meat.

I have little to no faith in behavioral modification at the population level. Other than teeth brushing, I can’t think of anything that has really worked. Diets, exercise programs, getting people to take their medicines—they all have similar recidivism curves where you can get pretty good adherence for a number of months but they fail universally for almost all of the people after a year or so. When it comes to life expectancy, you’re dealing with behaviors you need to modify for decades, not just a few months.

Gavalas: Yoga and meditation can help. They have been developed over millennia from the work of the first yogis. There was subjective evidence for thousands of years that claims for the benefits of yoga were true, but I’m pleased to say that after multiple studies have been done, many of those claims have been supported medically. One study, for example, found that yoga and meditation increased or maintained telomere lengths in participants. Telomeres lengthening is associated with increasing a cell’s longevity.

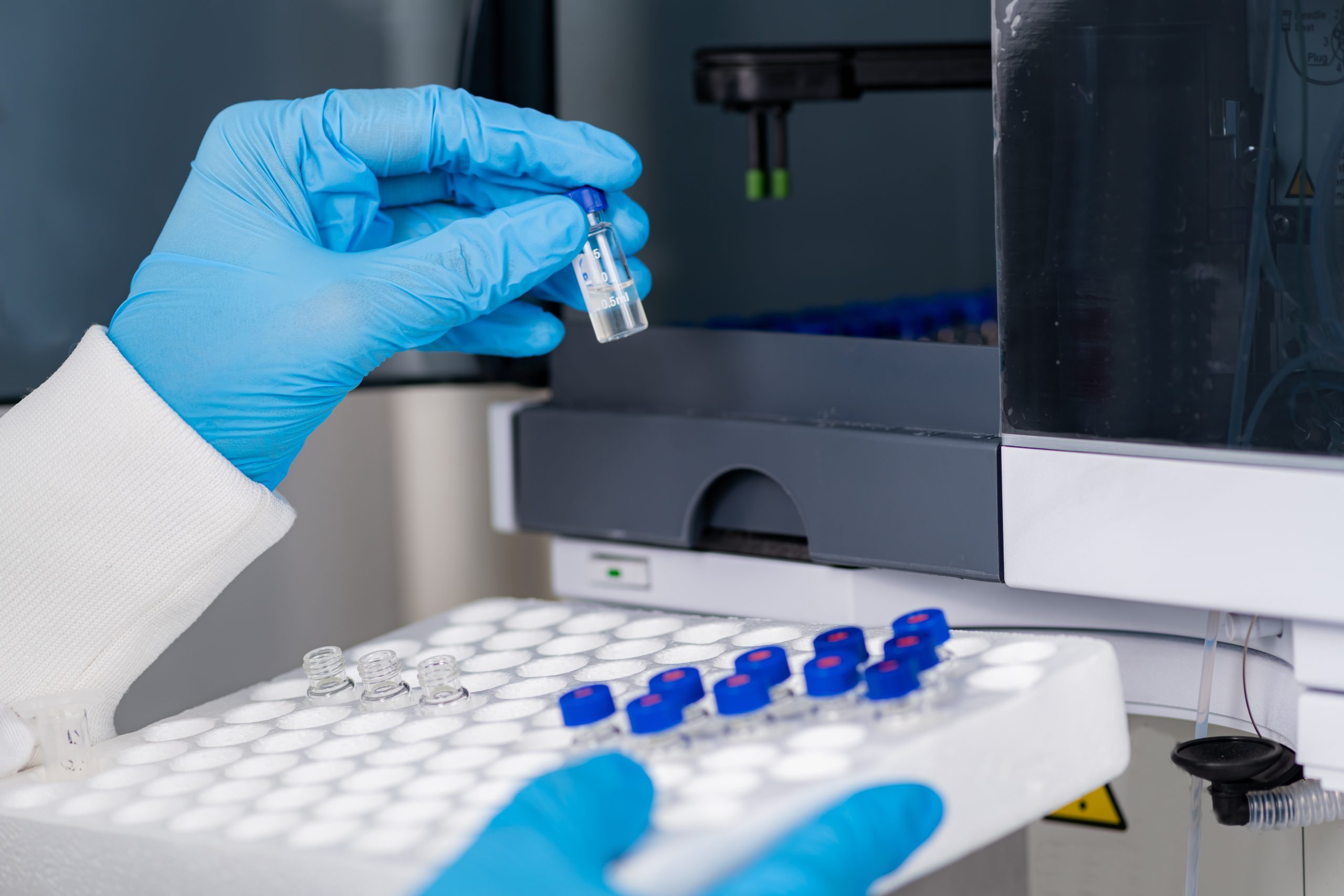

de Grey: Scientific advances. Rejuvenation procedures will recondition the body at the cellular and molecular levels. They will begin with surgery to replace aging organs with new ones grown in the laboratory. That will advance to repairing organs in place with injections. Eventually, oral-administered medicines will repair organs.

What’s the most important action a person can take to increase lifespan?

Greger: The No. 1 thing to do is eat healthfully because not eating healthfully is the No. 1 cause of death and the leading cause of disability. Eating healthfully means centering your diet around the healthiest foods out there. That’s food from fields, not factories—real food that grows out of the ground. Legumes are the No. 1 dietary predictor for survival. The No. 2 thing to do is you stop smoking because that’s the No. 2 leading cause of death.

Gavalas: I prescribe the six ways to move your spine, even if you just did a simple five-minute program for that, depending upon your limitations.

Macciochi: You can definitely maintain your immune system. The foundations would be taking care of your stress, getting good quality and quantity of sleep, eating a balanced diet, not being in an energy surplus or an energy deficit, and not having any nutritional deficiencies.

One of the best ways is through exercise and movement. After our 30s, muscle mass starts to decrease at a more accelerated rate, and if we don’t use our muscles we lose them. That means not only doing cardiovascular fitness like walking, running, cycling and swimming but also resistance-based exercise.

If we keep using our muscles doing resistance-based exercise, our muscles produce a special molecule called interleukin 7, which keeps us young and healthy and rejuvenates the thymus gland, which starts to shrink in our 20s. We can directly tap into that if we keep being regular exercisers.

We also have to look at inflammation. This is one of our immune system’s defense mechanisms that we use to get rid of infections and heal tissues and wounds. But inflammation tends to go up as we age, and as our immune system cells get older they become senescent so they start spitting out inflammation without any sort of proper regulation. This is one of the key things that ages us.

an American holistic health practitioner, yoga therapist, exercise physiologist and founder of galenbotanicals.com, has written 14 books and made numerous videos on yoga, meditation and health, including The Yoga Minibook for Longevity. Her latest book, The Yoga Therapy Guide, is scheduled for release in June. She emphasizes that science verifies the health benefits of yoga.

@elainegavalas

Buettner: Focus not on your lifestyle but on your environment. You’ll fail if you focus on your lifestyle. At least 97 out of 100 will fail. Take stock of your social situation, your four or five best friends.

If your three best friends are obese and unhealthy, you’re about 150% more likely to be overweight yourself. So you want to curate an immediate social network of people you’re going to see with some regularity, and those people’s idea of recreation is some physical activity you like. It could be golfing. It could be bicycling. It could be gardening. It could be walking. It doesn’t matter.

You should have one or two vegan or vegetarian friends. Beyond a shadow of a doubt, eating plant-based food is going to lower your chance for chronic disease. Whole, plant-based food—not Oreos or Doritios. Those friends are going to require that when you go out to eat there are plant-based options. When you go to their house, you’re eating plant-based foods and learning how to like it, learning how to cook it.

A number of things have been shown to lower the amount of junk food you eat: Not having a toaster on the counter, not having a junk food drawer, not putting salty snacks on your counter and not having a TV in your kitchen—these things all work at minimizing mindless eating.

Every time you go out to eat, you consume about 200 to 300 more calories than you would if you ate at home. Those calories tend to be higher in sodium and sugar than you would have if you ate at home where you could control the ingredients. Americans eat out on average 110 times a year.

You want friends who care about you on a bad day. We all have lots of friends we can sit around and gossip with or get business tips or exchange jokes, but when you’ve just been fired or your portfolio is down, you need a couple of friends who care about you no matter what.

Think about setting up your home. I call it “de-conveniencing.” You don’t want a home that gives you maximum comfort. You want to be nudged into movement. You can engineer a lot of movement by doing something by hand like kneading bread, opening cans, opening your garage door, pruning your garden with hand clippers and shoveling your own snow.

de Grey: Look to the future. Act to hasten research, which inherently will increase not only your chances but everybody else’s chances of living long enough to take advantage of advances that will lead to better health. And that advocacy for research can happen in many ways, depending on who you are. Wealthy people can support the research financially, and scientists can support the research by choosing research areas that have the most impact in this space. Journalists can get experts on air to raise the quality of information that the general public has access to. All these things should be done—everybody can do advocacy.

Where should readers seek advice on lengthening their lives and improving the quality of life as they age?

Buettner: I would get a plant-based cookbook. Dr. Greger’s got a good one. I have The Blue Zones Kitchen, which I just published. It doesn’t have to be one of our books—there are lots of good ones out there. Invest the time to try 10 recipes that you think you’ll like—plant-based recipes, whole food. Learn how to make them, but you need to make enough different ones so you find a handful you love.

Gavalas: Many talented people have made videos to instruct people in simple yoga practices. Some are on YouTube. Follow along with them, and you don’t even have to be in a specific program. A lot of this you can get for free if you just know where to look and go to a reputable yoga teacher or therapist.

an American physician, author and speaker, advocates a whole-food, plant-based diet and opposes animal-derived foods. His work demonstrates that the foods he recommends can help prevent or reverse chronic diseases. He’s a founding member of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine and the author of the books How Not To Die, How Not To Diet and The How Not To Die Cookbook. His book How Not To Age is scheduled for publication in 2022. His nonprofit website, NutritionFacts.org, provides free daily science-based videos and articles.

@nutrition_facts

Greger: There’s really only one source of information for something as life-and-death important as how to take care of yourself, and that is the peer-reviewed medical literature. Nothing else comes close. So, rather than having someone tell you what the literature says or cite the literature, the best place to go is to read the original studies themselves. That’s where all our knowledge comes from. They can go to the PubMed website—that’s the database of the National Library of Medicine. It’s free and you can type in any topic.

What should society do to increase longevity? Is it happening?

Macciochi: Your immune system is a societal issue, really. We can focus on the things that we can control, but we have to have socioeconomic change and psychosocial change to combat things like loneliness—this has been known to disrupt our immune system. Negative emotions and stress are pervasive in our society, and it’s something that we don’t acknowledge as being a detriment to our health and longevity.

Greger: Government could make the default option the healthier option. We taxpayers subsidize the sugar industry and subsidize the corn industry to make corn syrup and dollar-menu burgers raised on cheap feed for livestock. We subsidize some of the worst possible foods. Why? Because that’s where the political power is within the beltway. But why not subsidize healthier foods? Why not subsidize fruits and vegetables?

Buettner: In the Blue Zones Projects, we go into cities where both the private and public sectors invite us in. We begin with the central tenet that we’re not going to try to change people’s behavior. We’re going to change their environment so they’re set up for success. We have three squads in each city. The policy squad works with local government to draft ordinances that support good health, like limiting the number of fast-food restaurants. A second team issues Blue Zones certifications for schools and businesses that comply with health guidelines. The third team works to convince 15% of the population to sign a pledge to curtail bad habits and thus preserve their health.

We have 30 or so different policies and procedures that cities can implement that will build streets not just for cars, but for humans. There’s something called complete streets—ordinances that require that every five to seven years, streets are redone, and it’s required that when they’re redone they’re assessed for bike lanes, sidewalks and trees. There’s an aesthetic element too. People are way more likely to walk on a beautiful street than they are in an ugly street. We try to favor the pedestrian over the motorist.

So far, we’ve been very successful in Hawaii, Los Angeles, and in Naples, Fla. Fort Worth, Texas, was a big win recently. And now we’ve just been hired to go to work in Orlando; Austin, Texas; and Jacksonville, Fla.

Our work in Blue Zone Projects occasioned a 3% drop in smoking and about a 6% drop in obesity—all of that accomplished by cities and groups working together. When economists take those numbers and calculate the commensurate drop in lung cancer, heart attacks and rates of diabetes, they can compute the savings from preventing diseases. A heart attack costs about $120,000, and somebody’s got

to pay for that.

Are you particularly annoyed by any one threat to good health?

Buettner: A neighborhood where there’s no fast-food billboard advertising has about 10% lower rates of obesity than an identical neighborhood with no billboards advertising fast food. If you live in a neighborhood with more than six fast-food restaurants in a quarter mile radius of your home, you’re 40% more likely to be obese than in a same neighborhood where there are fewer than three fast-food restaurants.

And here’s another: All the incentives in America’s health care system are lined up behind mitigating sickness. Nobody makes money when you stay healthy. When you look at places like Costa Rica, their incentives are mostly lined up behind health. Lo and behold, they have about half the rate of middle-aged cardiovascular mortality we do in the United States, and they spend one-fifteenth the amount we do on health care.

Greger: Most doctors were never taught about the impact health and nutrition can have on the course of illness. So they graduate without this powerful tool in their medical tool box. This is not to say there aren’t institutional barriers, like time constraints and lack of reimbursement. But in general, doctors simply aren’t paid for consulting or counseling people on how to take better care of themselves. Drug companies also play a role in influencing medical education. Ask your doctor when she was last taken out to dinner by Big Broccoli. It’s probably been a while.

de Grey: A lot of people find it more emotionally acceptable to view aging as some kind of blessing in disguise. So then they don’t have to think about it, even though that has no logic to it whatsoever. There’s a lot to be thought about with regard to a world in which nobody’s dying and everybody is getting older and older even though they are healthy. Where will we put all the people? And dictators will live forever. Remember that longevity is only a side effect of health.

a British immunologist, professor, fitness instructor and author, has studied the link between lifestyle and health for more than 20 years. At home, her family puts knowledge of nutrition to good use by cooking meals influenced by her farm-to-table Scottish roots and her husband’s Italian culinary heritage. A U.S. edition of her book, Immunity: The Science of Staying Well, is scheduled for publication this year.

@drjmacc

Macciochi: We have to take care of misinformation online and approach the headlines with caution because there’s a lot of airtime to fill. The news media are really quick to jump on any new information that’s coming out. We should be cautious of anyone who’s selling any sort of snake oil type of solution for coronavirus because the truth is we really just don’t know much about it at the moment.

What else should we be saying about longevity?

Gavalas: The Vedas and other works from thousands of years ago were just saying move the spine. The ultimate goal was to produce comfort and live long enough so that you could reach enlightenment. That has grown into what we’re doing now, and so many other benefits could come from it.

Macciochi: The immune system is one of the main drivers of aging. We should be conscious of it and we should protect it. We only tend to think about it when we get those familiar symptoms of a cold or flu, but it’s actually working hard all the time and we should really be conscious of that.

Buettner: Everybody’s hair is on fire about the coronavirus right now. Some projections say a million or so people who could die this year. But way more people are going to die from a chronic disease, which has completely receded into the background. Chronic disease is a much bigger health concern for America than infectious disease. I’m not diminishing the coronavirus problem, but we can’t completely shut off the spotlight on chronic disease problems like this.

de Grey: Talk about health, not about longevity. The more you talk about longevity, the more people say they’re not interested. People get so nervous about what increased longevity would make the future look like that they think we should slow down the progress of research to get the health benefits that everyone actually wants.

Greger: I just encourage people to feel free to check out my work. I would love to help people live long healthy lives in any way I can.