Market Implications of a Second Wave

The first wave of the coronavirus pandemic is currently rolling across much of the world, with devastating results.

Over 4.5 million people are known to have been infected by COVID-19, and there have been more than 300,000 associated deaths. However, both of those numbers are likely much higher in reality, given the limited availability of testing in some parts of the world.

Because the first wave of the virus hasn’t yet receded, it may seem premature to start worrying about the second wave.

However, there’s a large group of investors and traders that prefer to take a longer-term view of the financial markets, which means that some are likely already trying to figure out the potential implications of a “second wave” of the virus—particularly as it relates to the economy and financial markets.

In pandemic lexicon, a “second wave” is traditionally referred to as a second period in time characterized by a high rate of infection (and often death), typically arriving some months after the first wave has “peaked.”

Looking back on the deadliest pandemics in history, most of them have been associated with a second wave, and in some cases even a third or fourth wave.

In those epidemics, the illnesses responsible had the twin attributes of being extremely contagious, along with moderately fatal. It should be noted that infectious diseases which are “extremely” fatal often extinguish themselves quickly, because the majority of hosts succumb to the disease before they are able to spread it on a mass scale.

Given the nature of the coronavirus epidemic in 2020, it appears outwardly that COVID-19 shares some of the characteristics of previous pandemics such as the Spanish Flu, the Asian Flu, and the Hong Kong Flu, in terms of being highly contagious and moderately fatal. The mortality rate of those illnesses, including COVID-19, range between about 0.5% and 2.0%.

The unique problem presented by the current coronavirus strain is that it’s believed to spread even when hosts are not presenting noticeable symptoms – a particularly complex dimension of COVID-19. One can only hope that future illnesses don’t mimic this characteristic.

On top of all that, it’s possible that the current coronavirus could mutate into something worse, which has also occurred previously in history.

Circling back to second wave theory, it has been confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that the likelihood of another severe outbreak in the coming fall/winter is strong. Talking recently to The Washington Post, CDC director Robert Redfield said of the second wave, “There’s a possibility that the assault of the virus on our nation next winter will actually be even more difficult than the one we just went through.”

Referring to the upcoming fall/winter seasons, Redfield added, “We’re going to have the [seasonal] flu epidemic and the coronavirus epidemic at the same time.”

That viewpoint has been echoed by other global experts, including leading Chinese scientists that recently warned, “a second wave of the virus could be harder to contain.”

Not discounting the very serious threat to public health represented by a second wave of the virus, investors and traders with a longer-term view of the financial markets will also likely be following “second wave” projections extremely closely in the coming weeks.

At the top of the list of market-minded considerations is the notion that a second wave of the virus could result in additional lockdowns of the global economy, which would mean that businesses and workers inside the global economy haven’t yet passed through the “eye of the storm.”

This contrasts somewhat with recent euphoria in the equity markets, which have risen as much as 30% since the bottom observed on March 23. In fact, as of May 10, valuations in the U.S. stock market seemed to suggest that serious impairment of the American wasn’t expected beyond 2020.

The Price/Earnings ratio, known as the “P/E Ratio” for short, is one of the best-known metrics used on Wall Street to analyze relative market valuations. This ratio measures the stock price of a given company against its earnings per share (EPS). For example, a PE ratio of 15 suggests that a company’s stock is trading at 15 times estimated earnings for a given period of time.

For the overall S&P 500, the P/E ratio has typically averaged somewhere between 15 and 16 in modern market history. However, there are of course instances when it has climbed above, or dropped below, that level. Some market technicians watch extremes in the P/E ratio of the overall stock market closely for signs that equity valuations may be too rich, or too cheap, according to this historical metric.

Interestingly, that gauge (as of May 10) stood at about 20, meaning that according to the P/E measurement, equity valuations in the United States were on the rich side, relatively speaking. For comparison, this metric fell below 12 during the bear market correction during the Great Recession.

When looking at the forward P/E ratio of the market based on earnings projections for 2021, the ratio does drop to about 17 (based on May 10 data). The problem with both of these figures is that ongoing and future earnings are such a big unknown.

At this point, there’s a wide range of potential scenarios that could play out during the remainder of 2020 in terms of corporate earnings, which in turn means that 2021 profitability is even cloudier.

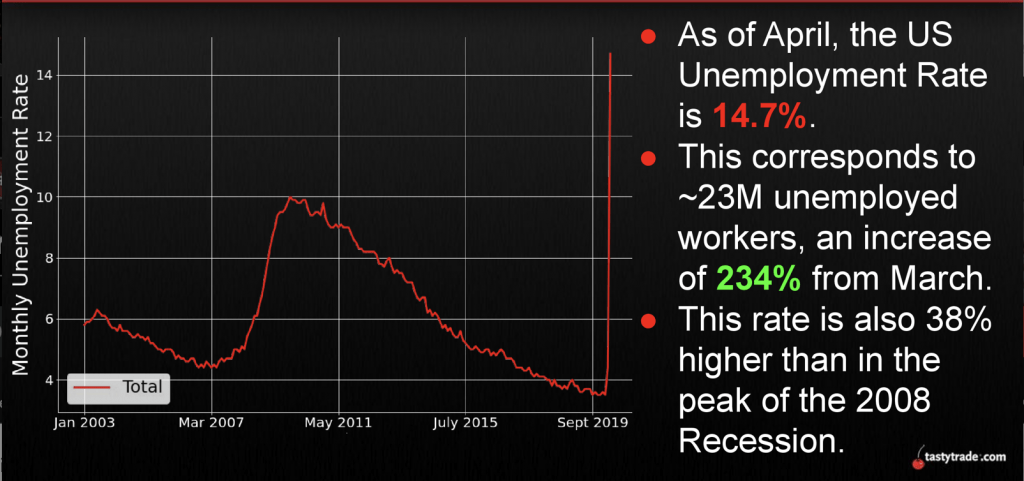

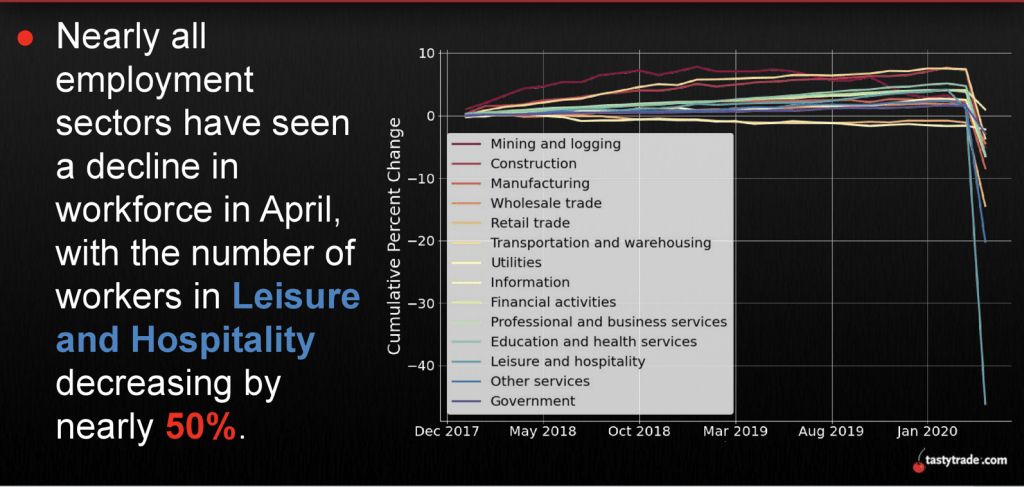

Another factor to keep in mind are the elevated levels of unemployment that have been observed during the spring of 2020 in the United States. On May 8, the U.S. government revealed that the country’s unemployment rate was running at nearly 15%, which is the highest level on record since the Great Depression.

Even more disconcerting is the widespread expectation that the May figure will be revised upward when the June unemployment data is released in a couple weeks time. It’s believed the current unemployment rate may be 20%, or higher.

The two graphics below provide additional insight into the current unemployment situation in the United States:

One possible silver lining in the most recent unemployment report was that a large portion of those workers reporting as “unemployed” indicated that their expectation was that it would only be a temporary layoff. On May 8, when the data was released, it appeared that the financial markets interpreted the “temporary” aspect of the data as a positive, as equity indices went higher that day.

That being said, alternative perspectives have suggested that interpreting the unemployment disaster currently unfolding in the United States as only “temporary” may be overly optimistic.

To that point, a report released by the University of Chicago on May 11 suggested that 42% of the recent layoffs in the United States could be permanent. That estimate paints an alarming picture, and one that lines up better with the strong possibility of a second wave of the virus striking in the fall/winter.

On May 13, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell, appeared to side with the more pessimistic outlook, suggesting that risks presented by the coronavirus pandemic could result in a “prolonged recession and weak recovery.”

The Chair of the American central bank further elaborated, saying, “A prolonged recession and weak recovery could also discourage business investment and expansion, further limiting the resurgence of jobs as well as the growth of capital stock and the pace of technological advancement,” and “the result could be an extended period of low productivity growth and stagnant incomes.”

Powell even appeared to address the question of a second wave when he asked rhetorically, “Can new outbreaks be avoided as social distancing measures lapse?”

As of now, it’s arguable that the development of a second wave in fall/winter may be one of the most important factors determining how quickly the U.S economy can rebound.

Other factors that are sure to play a big role in determining how quickly the economy rebounds would include: actions taken by Federal and state governments to provide relief and stimulus, policy decisions of the Federal Reserve, and key milestones related to the development of potential treatments/vaccines for COVID-19.

If a second wave doesn’t develop, or it’s weaker than anticipated, it’s plausible the American economy could rebound in the coming months, and position the country to enjoy a robust economic year in 2021. Under this scenario, it’s likely the unemployment rate in the United States would pull back substantially in the second half of 2020.

Alternatively, if a second wave does indeed materialize, and it’s as grave as most experts have predicted, then one could envision elevated levels of unemployment persisting through the end of 2020, and into 2021. If this second scenario comes to pass, the U.S. government (like many other sovereign nations) will undoubtedly be forced to intervene with trillions more dollars in assistance and stimulus.

Under that scenario, one could envision a strong rebound in market volatility at some point down the road, given that uncertainty around the performance of the economy and corporate earnings would remain high.

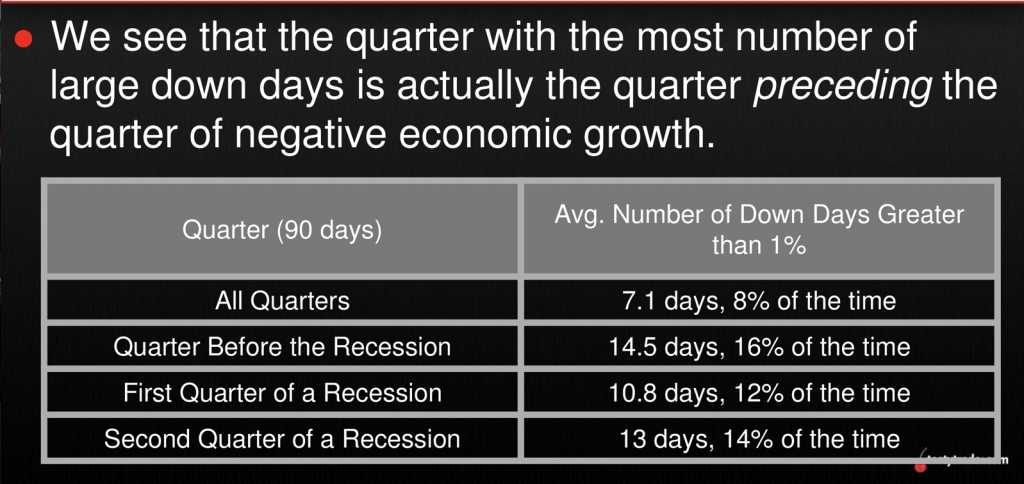

Previous tastytrade research has illustrated that historical recessions in the United States have been accompanied by dramatic selloffs in equity valuations. However, that research also revealed that such corrections often materialize early on in the cycle, as outlined below:

Nobody knows for certain how the economy and equity markets will behave through the remainder of 2020, and through the start of 2021. What is certain is that a destructive second wave of the coronavirus, if it does materialize, wouldn’t likely be kind to either.

For more information on the historical behavior of equity markets heading into economic recessions, readers may want to review a recent episode of Market Measures on the tastytrade financial network when scheduling allows. Additional information on the current U.S. unemployment situation and how it compares to the Great Recession is also available via this link: Tasty Extras.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.