Next Black Swan Could Be China’s Debt

Ballooning corporate debt in China has pushed the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio above 300%, raising anxieties over potential risks to the system.

Back in February, Luckbox suggested that early reports of a super-contagious new strain of the coronavirus spreading in mainland China could represent the next black swan event for the global financial markets. Virtually all investors and traders on earth know what happened since.

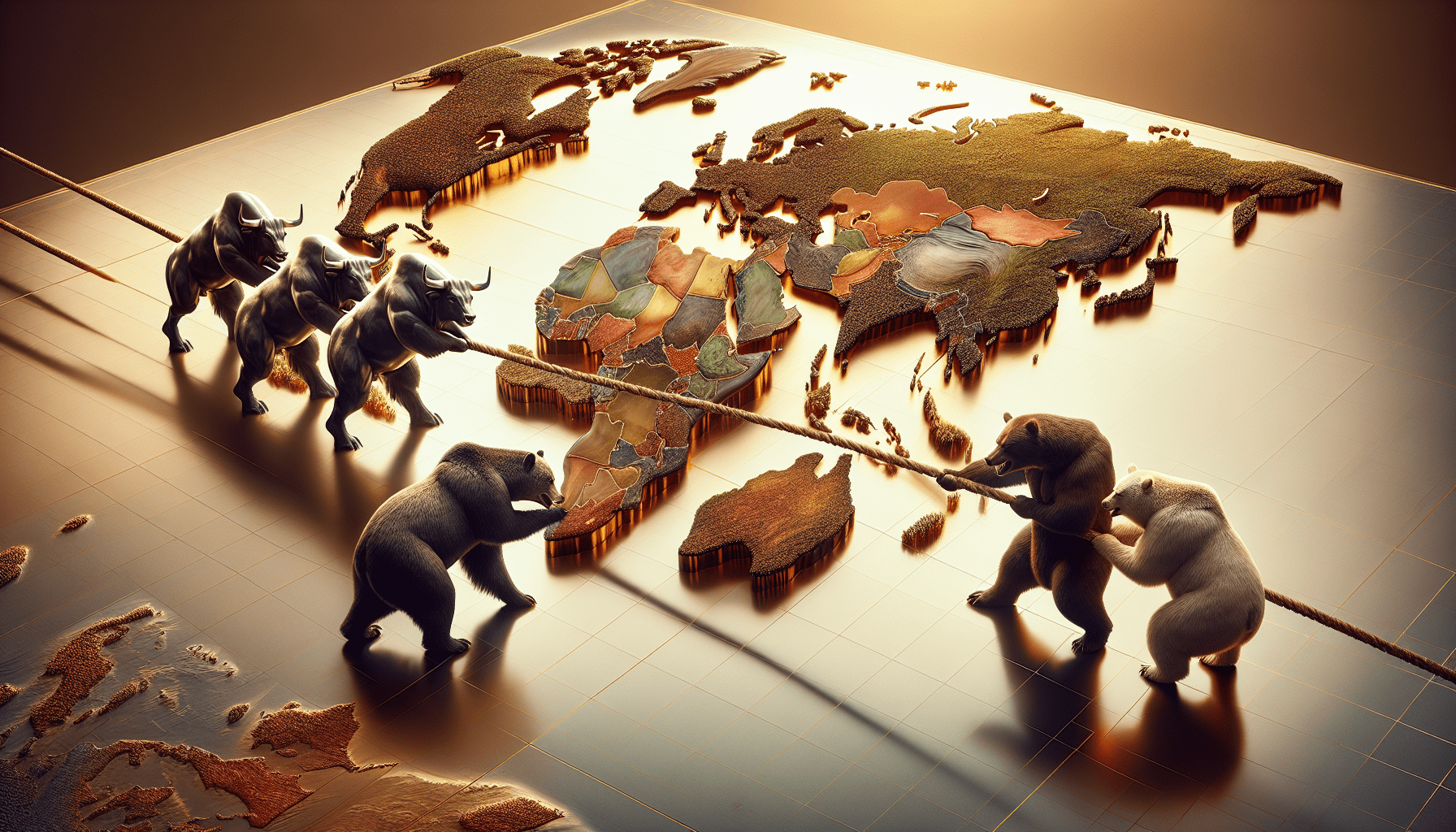

Black swans, by definition, are sudden, unexpected events that catalyze jagged corrections across the universe of investable assets.

While black swans can creep up in an unanticipated manner, that isn’t always the case. There were some experts who correctly predicted the onset of the Global Financial Crisis, which raged in 2008-2009.

With safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines expected to be available in the coming months, investors and traders with longer time horizons can now shift their focus to other potential events that could disrupt the global financial markets when the pandemic subsides.

One narrative savvy investors and traders might want to start following is the Chinese debt situation.

Experts in economics have long warned that the absolute levels of debt in China could at some point catalyze a financial crisis. Those fears are founded on red-lining levels in the Chinese debt-to-GDP ratio—a situation that’s further complicated by a lack of transparency into the financial dealings of the Chinese government.

In basic terms, the public debt-to-GDP ratio measures a country’s total debt (government, corporate and consumer) relative to its gross domestic product (GDP). The metric is commonly used to evaluate a country’s financial health, and more specifically its ability to make good on its debts.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is calculated by adding up all the public debt in a given country and dividing it by GDP. The result is a decimal converted to a percentage, which can then be compared against global benchmarks.

For example, the current debt-to-GDP ratio for the United States is roughly 98%, calculated by taking the estimated net public debt ($20.3 trillion) divided by the estimated GDP ($20.6 trillion). For context, the World Bank conducted an extensive study on this metric and concluded that a reading above 77% was suboptimal, and implied that a country’s economic potential could be limited by excessively high debt service.

Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc upon most countries’ debt-to-GDP ratios in 2020 because the world has been grappling with the dual threat of declining productivity combined with a rising need for fresh liquidity—the latter of which has been necessary to fight the pandemic (i.e. public health funding) and to stimulate lagging economies.

In the United States, the 2020 situation has been especially dire, with public debt spiking dramatically as a result of various government interventions. Case in point, the public debt-to-GDP ratio in the U.S. was 79% at the end of 2019, before rising to 98% in 2020. Projections suggest it could spike above 100% in 2021, as illustrated below.

In some regards, China has been fortunate this year because it hasn’t been forced to assist its economy as vigorously as the U.S., ostensibly because the country contained the spread of coronavirus more efficiently. However, the debt-to-GDP load in China was already sky-high before the pandemic.

In the last quarter of 2019, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) estimated that the public debt-to-GDP in China was 302%. By May of this year, it had risen to an estimated 318%—the largest quarterly increase on record for the Middle Kingdom.

Superficially, that degree of indebtedness relative to annual productivity may already seem akin to a flat line on an electrocardiogram. Strangely, however, those aggressive levels of debt haven’t generated the same level of alarm as they might in North America or Europe.

That may in part be due to the emergence of a new theory of macroeconomics which has put forth that the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009 shifted the sovereign debt paradigm.

Known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), this school of thought argues that rising piles of public debt don’t represent the same risk as they did before the Great Recession. Critics, however, argue that the current era of central bank “money printing” in no way guarantees a “free lunch” in terms of unbridled debt accumulation.

MMT aside, many global economic experts have warned that China’s binge on debt is a clear and present threat to the global financial system. And while no two financial crises are ever the same, a debt crisis in China would likely materialize in the form of corporate loan defaults, much like consumer mortgage defaults catalyzed the previous Financial Crisis in the United States.

The situation in the U.S. spiraled in 2008-2009 because financial institutions tied to those bad loans were undercapitalized, and many ultimately succumbed to bankruptcy. As a result, the American government was forced to backstop the financial system using the “full faith and credit” of the federal balance sheet to reinflate the system.

In the case of China, it’s already been well established that the country’s economy is littered with a boatload of bad debts, particularly of the corporate variety (note ballooning corporate debt in graphic below). The difference in China is that the country’s national savings rate is among the highest in the world, meaning Chinese banks are theoretically better capitalized and potentially better positioned to absorb a bigger shock to the system.

Few are eager to see that theory put to the test.

Unfortunately, several high-profile corporate defaults have popped up on the radar in China over the last several weeks, which has raised concerns that the Chinese debt bomb may be ticking toward a critical level.

One high-profile default occurred Nov. 17, when a major Chinese chip manufacturer failed to service a corporate bond. At that time, the China Chengxin Credit Rating Group announced that the Tsinghua Unigroup had defaulted on a privately placed domestic bond worth $197 million. Chengxin noted that Tsinghua Unigroup was unable to successfully renegotiate with creditors to extend the repayment deadline.

Another such case was reported Nov. 13 and involved a state-owned enterprise. That default was by the Yongcheng Coal and Electricity Group and involved principal and interest payments on an overdue commercial paper loan of $150 million. Moreover, it led to concerns that the parent company of Yongcheng, the Henan Energy and Chemical industry, could also be in trouble.

Tensions over this particular event were so high that a meeting involving central banking authorities was called to address the situation. The urgency could be linked to the fact that the Huachen Automotive Group, another state-owned enterprise, also defaulted on a debt payment recently.

Three defaults certainly don’t equate to a crisis, especially given that China possesses the second-biggest onshore bond market on earth ($13 trillion). But one also wonders if the full picture has been disclosed. The Chinese government is known to clamp down on negative media coverage, preferring to handle internal issues without the annoyance of external scrutiny.

Luckbox covered all risks in China extensively in this issue.

Moreover, the recent defaults have had real implications on the Chinese corporate debt market. Nikkei research estimates that 57 companies have cancelled plans to issue a combined $6.72 billion in new fixed income in the wake of the default news, likely because of softer demand in the market.

Suffice to say, antennas in the international financial community are up, as they should be, for all investors and traders.

To learn more about trading black swans, readers can review a previous installment of Everyday Trader on the tastytrade network. To follow all the daily action in the markets, readers may also want to tune into TASTYTRADE LIVE, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. Central Time, when scheduling allows.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of Luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.