Now That We Have Seen Negative Oil, What About Negative Gas?

No matter what happens in the financial markets over the remainder of 2020, one lasting memory from the coronavirus crisis will undoubtedly be the fact that crude oil futures turned negative for the first time ever on April 20, 2020.

Simply put, this occurred because of a cratering in demand amid a vast relative oversupply—the usual suspects when it comes to market pricing.

In the spring of 2020, demand for crude oil plummeted unexpectedly as the coronavirus spread outside of China and forced lockdowns of economies across the globe. Simultaneously, the crude supply network couldn’t adjust quickly enough to the new market dynamic, which meant there was suddenly a huge surplus of this vital energy source on the market.

On April 20, the day before that month’s crude oil futures contract was set to expire, many crude oil market participants were forced to sell their positions at unexpectedly low prices to avoid taking physical delivery of a commodity they couldn’t sell (and likely had no place to store).

As it turned out, the price at which others were willing to take on those delivery obligations translated to a negative price, meaning holders of long contracts were forced to pay other market participants to assume that burden.

In the wake of that dramatic day, global producers acted swiftly to “shut in” production (i.e. stop production) in order to more closely balance demand with supply. Alongside that effort, some economic lockdowns were lifted, which catalyzed a minor resurgence in demand.

So far, negative prices in crude oil haven’t been repeated. However, that’s not to say it couldn’t happen again at some point in the future. The CME clearly had that possibility in mind when it added negative strikes to crude oil futures options going forward.

This situation makes observers wonder if negative prices could appear in another product at some point in the future, too. Natural gas, for example, is another key international energy commodity that has been extremely sensitive to changes in supply and demand dynamics linked to the health of the global economy.

So far during the coronavirus crisis, natural gas prices have only suffered slightly—at least compared with crude oil.

Natural gas is priced in terms of millions of “British thermal units,” instead of barrels because it’s a gas. During the height of the recent crude oil crisis, natural gas prices dropped from about $2.00/MMBtu to $1.63/MMBtu, a drop of just over 18%.

However, prices since that time have rallied back to nearly $1.85/MMBtu.

It’s believed that natural gas prices have thus far avoided the same fate as crude oil because the coronavirus crisis impaired transportation demand to a much greater degree than the powering/heating/cooling of homes and businesses—several of the primary uses of natural gas in the modern world.

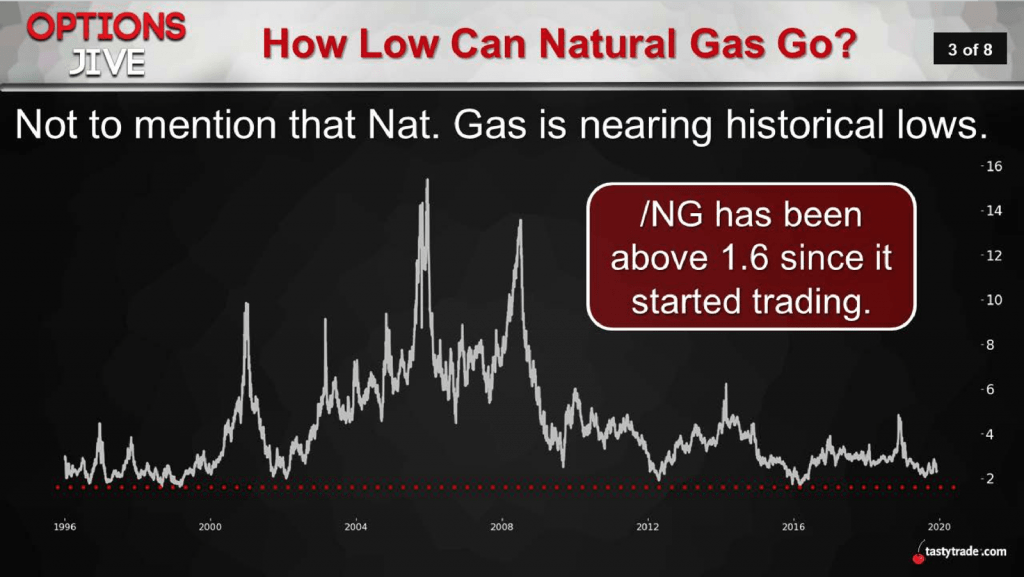

Having said that, a broader, negative trend in natural gas prices was established well before the coronavirus appeared on the global radar, as shown in the historical price chart below:

From the start of January 2018 to today, natural gas prices have dwindled from roughly $3.45/MMBtu all the way down to $1.85/MMBtu—a 46% decline over that period.

The commodity has been under pressure for a couple of reasons, but mainly due to a rising pool of available global supply. A warmer-than-expected winter in 2019-2020 also dampened demand, which further contributed to slackening prices.

Considering the broader price trend, one might have assumed that prior to the coronavirus crisis, natural gas prices may have been more susceptible to a slip into negative territory.

Those making that assumption would be correct, because natural gas prices have actually dipped into negative territory once before 2020. In the spring of 2019, natural gas prices for “next day” delivery at the Waha hub in West Texas dropped into negative territory for the first time in American history.

While that occurrence drew much less attention than the recent drop in crude oil, it was unprecedented and resulted in a similar outcome—sellers were paying buyers to haul it away.

Once again, the reason behind the extreme price drop was linked to supply and demand.

However, in this instance, the supply problem was associated with equipment failures at a natural gas pipeline. With the pipeline shut down and unable to transport natural gas, supplies at the Waha hub exceeded storage capacity, which in turn catalyzed the negative price event (one that lasted several weeks).

In a broader context, the situation at the Waha hub in 2019 was fairly similar to crude oil in 2020: too much supply. One difference is that natural gas futures didn’t go negative, it was only the “next day” delivery contract in natural gas that went below zero (about $9 below zero at its worst point) at Waha.

Interestingly, crude oil futures only went negative on the day before the contract was set to expire in April of 2020, meaning that was essentially a “next day” situation as well.

It’s believed that prior to March 2019, not one natural gas trading hub in the United States had ever recorded a negative cash price. But there were two such instances recorded in Western Canada during 2018 that are believed to be the first couple in North American history.

Given the above, it probably won’t surprise that natural gas prices at the Waha hub have actually traded negative in 2020, too. But instead of being linked to the coronavirus crisis, this situation was once again linked to the bottleneck at the hub, which is expected to be alleviated when a new pipeline goes into operation in 2021.

The above means that on several occasions in North American history there have been instances in which “next day” natural gas has traded in negative territory.

And while it would likely take an extremely disruptive event that affects the powering/heating/cooling of homes and businesses to push natural gas futures below zero, the possibility that it could occur at some point isn’t zero.

It should be kept in mind that natural gas storage facilities, like those for crude oil, are starting to inch toward their maximum capacity, and not just in the United States. If a second wave of the coronavirus ends up catalyzing a widespread shutdown of the global economy this fall/winter, and storage facilities get even closer to capacity, then the possibility of a negative print in natural gas futures will increase substantially.

In the near term, however, prices will continue to fluctuate as always—based on the expected demand for cooling this summer, as well as demand for heating next winter—projections that will play a pivotal role in natural gas pricing dynamics going forward.

In the medium term, energy traders would be well-advised to monitor projections for a second wave of COVID-19, as well as the ongoing global storage capacity for natural gas. Under the worst case scenario, it’s plausible that the same type of “perfect storm” which pushed crude oil into negative territory could become a greater concern for natural gas, too.

To learn more about the current trading landscape in the energy space, readers may want to review a recent episode of Futures Measures on the tastytrade financial network when scheduling allows.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. The contributor has an extensive background in trading equity derivatives and managing volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. The contributor is not an employee of luckbox, tastytrade or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about any of the topics covered in this blog post, or any other trading-related subject, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.