Trading the Surge in Major Corporate Bankruptcies

Three large regional banks have failed this year, but major corporate bankruptcies aren't just in the financial services sector.

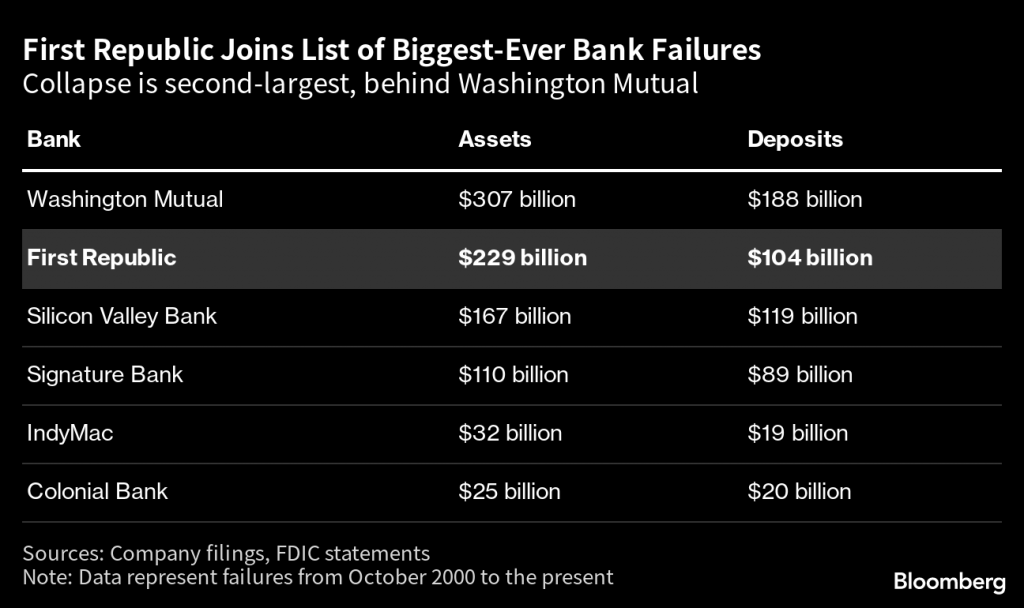

On May 1, the ongoing U.S. banking crisis claimed another victim—First Republic Bank (FRC).

The bank was seized by regulators on Monday morning, liquidated, and then sold to JPMorgan Chase (JPM). Reports indicate that JPMorgan acquired about $92 billion in deposits, $173 billion in loans and $30 billion in securities from First Republic.

As a result of these actions, all 84 of the former First Republic’s branches opened as usual on May 1, and are now operating as part of JPMorgan. However, it’s expected that First Republic’s shareholders will be completely wiped out as part of the deal.

The First Republic failure comes in the wake of the previous Silicon Valley Bank (SIVBQ) and Signature Bank (SBNY) failures, but it actually represents the largest bankruptcy in the financial services sector so far this year.

At the time it was seized, First Republic had roughly $229 billion in total assets, which was slightly more than the $209 billion held by Silicon Valley Bank when it failed in March.

That means the largest bank failure in American history—in terms of total assets—is still Washington Mutual, which had over $300 billion in total assets when it went bankrupt during the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis.

Overall, 2023 has been a rough year for the financial services sector, with three of the four largest bank failures in American history occurring during the first four months of the year.

That says a lot considering the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) shuttered 465 banks from the start of 2008 through the end of 2012. In comparison, the FDIC closed only 10 total banks from 2003 to 2007, and eight banks from 2018 to 2022.

Despite the slew of major failures in 2023, Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan, sounded cautiously optimistic on a May 1 conference call with reporters and investors saying, “This part of this [banking] crisis is over.”

Only time will tell if that prediction proves accurate. In the wake of the First Republic failure, the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF (KRE) dropped another 8%. And since the start of 2023, KRE is now down almost 35%.

But, the 2023 bank failures don’t tell the full story. Major corporate bankruptcies are up this year across the board, not just in the financial services sector.

Corporate bankruptcies trend toward record levels in H1 2023

Looking beyond the financial services sector, major corporate bankruptcies are on the rise across the board in 2023. A major corporate bankruptcy is defined as one that involves a company with more than $50 million in total liabilities.

When it comes to major corporate bankruptcies, only two calendar years in the 21st century have started on worse footing than this year—2009 and 2020.

The current rate of bankruptcies is still well behind the corporate destruction observed in the wake of the 2008-2009 Financial Crisis. However, the rate of major bankruptcies in 2023 is on pace with what was observed during 2020, when the world economy was reeling from the initial spread of COVID-19.

The torrid pace of major bankruptcies during the first four months of 2023 suggests that elevated interest rates—and the resulting slowdown in the U.S. economy—are finally starting to weigh on the corporate sector.

In addition to the three major banks, some of the other high-profile bankruptcies in 2023 include a mix of public and private companies:

- Avaya Inc. (AVYAQ)

- Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY)

- Boxed (BOXWQ)

- Cineworld

- David’s Bridal

- Diamond Sports Group

- Forma Brands

- Independent Pet Partners

- Loyalty Ventures (LYLTQ)

- Party City (PRTYQ)

- Serta Simmons Bedding

- Si02 Medical Products

Considering that the U.S. Federal Reserve is currently projecting the onset of a mild recession at some point in Q2 or Q3, it’s almost guaranteed that some additional high-profile companies will fall into bankruptcy at some point in 2023.

In the wake of the First Republic’s failure, investors and traders appeared to zero-in on several additional regional banks. For example, on May 2, LendingTree (TREE), Metropolitan Bank (MCB), PacWest Bancorp (PACW) and Western Alliance Bancorporation (WAL) were down 25%, 20%, 27% and 15%.

While it’s impossible to predict if or when another bank failure will strike, the market hasmidentified these four institutions as possible candidates. PacWest looks particularly vulnerable, considering that its shares are down more than 70% so far this year.

Trading bankrupt and delisted stocks

When a public company goes bankrupt—whether it be a bank or a company from another business sector—its shares are typically delisted from the exchange.

A delisting is basically the opposite of an initial public offering (IPO), and while the bulk of delistings are involuntary, there are occasions when a company might voluntarily delist its shares.

The process is similar for both voluntary and involuntary delistings, and the reasoning behind a given delisting is important because the impact on a company’s underlying share price can be vastly different.

For example, Luckin Coffee (LKNCY) was involuntarily delisted back in 2020 by Nasdaq because the company failed to file its annual report. In that case, the company confessed to falsely inflating its sales figures, and the stock plummeted below $1/share.

In contrast, DiDi (DIDIY) announced plans to voluntarily delist from the New York Stock Exchange in December 2021, and then executed on that plan in June 2022.

In the wake of that December announcement, DIDI shares suffered only marginally, dropping from about $7.80/share down to about $6/share. DIDI told shareholders it was forced to delist in order to resolve a cybersecurity probe at home in China.

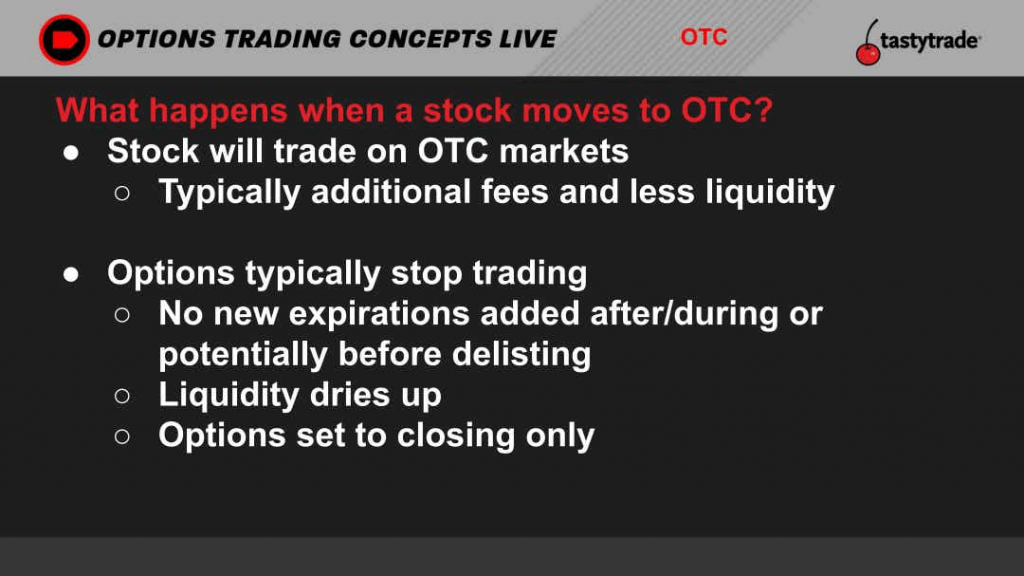

What’s important to keep in mind is that delisted stocks don’t necessarily stop trading altogether.

Once a delisting occurs, most stocks continue to trade over-the-counter (OTC) with a different (but similar) ticker. In the case of Luckin, the stock’s shares now trade under the ticker LKNCY for about $25/share—having climbed out of the sub-dollar-per-share depths. Luckin previously traded under the ticker “LK.”

Along those lines, DiDi continues to trade OTC under the ticker DIDIY, and Silicon Valley Bank continues to trade OTC under the ticker SIVBQ.

While OTC trading allows shares to remain active, it does represent a fairly big drop-off from a big board listing on the New York Stock Exchange or the Nasdaq. Most large financial firms are barred from trading or investing in OTC stocks, which means the profile and liquidity of an OTC listing will be greatly reduced as compared to a “big board” listing.

Investors and traders should also be aware that inadequate liquidity in OTC listings can lead to wide (i.e. inefficient) bid-ask spreads.

A bankruptcy-related delisting, or a potential delisting, can be a significant development in the life of a stock, and for this reason, investors and traders need to carefully monitor news announcements related to this topic.

Generally speaking, investors and traders can protect themselves from delisting risk by trading highly reputable companies with a long history of consistent profitability. Or by avoiding single-stocks altogether, in favor of exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

For more context on delistings, review this previous installment of Options Trading Concepts Live on the tastylive financial network. To follow everything moving the markets, tune into tastylive, weekdays from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. CDT.

Sage Anderson is a pseudonym. He’s an experienced trader of equity derivatives and has managed volatility-based portfolios as a former prop trading firm employee. He’s not an employee of Luckbox, tastylive or any affiliated companies. Readers can direct questions about this blog or other trading-related subjects, to support@luckboxmagazine.com.