Taking Futures to a New Level

|

Advanced uses of futures include scalping, pairs trading and delta hedging

Futures contracts offer retail traders some strategic advantages that aren’t available with stocks and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), including scalping, pairs trading and portfolio hedging.

Scalping may seem obvious, but futures scalping offers two advantages over scalping stocks or exchange-traded funds: tax efficiency and freedom from pattern day trading restrictions. Unlike stocks or ETFs, futures gains or losses are taxed at a generous 60/40 long-term/short-term tax system.

That means that no matter how long an investor holds the trade, the feds tax 40% of the profit/loss (P/L) for futures contracts at the standard income tax rate, but 60% of the...

Advanced

-

Hype and Skew

|Hyped-up stocks can have unusual option pricing with atypical option skew Look at prices of the Nasdaq ETF (QQQ) out-of-the-money (OTM) strikes for the April 14 expiration. They’re highest at… -

The Wisdom of Crowds

|To predict next year’s stock prices, look where investors are putting their money New variants of COVID-19 might drive stock prices lower, or President Joe Biden’s infrastructure plan might push… -

Smart Inflation Hedges

|Looking to take the sting out of an investment’s shrinking value? Ethereum and bitcoin have been anything but stable. Think gold. Is cryptocurrency the new inflationary hedge? Not for anyone… -

Paper Trading Just Got Better

|A new free tool enables investors to see the future of their trades tastytrade is offering investors a new free tool called Lookback that provides a risk-free environment to test… -

Three Ways to Play Long Odds

|Options enable active investors to quantify and manage risk. But sometimes they may wantto try for a big score with low-probability, high-return strategies. Investors want to see their portfolios grow… -

Next Level: Turning Vertical Spreads Into Ratios

|Any spread that involves at least two different legs, and a non-symmetrical number of contracts traded on each leg, falls under the umbrella of a "ratio spread." -

Breaking the Butterfly’s Wings

|Transform a low-profit, low-risk trade into one with higher profit but higher risk The butterfly, a low-probability, low-risk options trading strategy, doesn’t maximize profit, but it lessens risk. That’s why… -

Calculating Correlation

|Here’s how to compute the relationship between two stocks without having to leave home. Market correlation helps traders understand the relationship between two stocks or indexes. A table filled with… -

Arbitrage Secrets: How to Create ‘Free’ Butterfly Spreads

|When ratio spreads move into a winning position they can be converted into so-called “free” butterfly spreads. When taking a position in the market, most investors and traders seek to… -

How Much Volatility Is Too Much?

|Risk increases if a stock is too volatile or makes price moves far outside of what’s expected Options traders often gravitate toward highly volatile stocks. With volatility, they have greater… -

Tips for Trading Microchips

|Semiconductor stocks offer high volatility and extraordinary liquidity Tech stocks were the market to buy in 2020. While Covid-19 crippled many sectors, technology stocks bloomed with a 40% rally from… -

Make History Work For You

|Google provides historical stock prices traders can study or use to create a personalized portfolio tracker Anyone with a Google account can easily download historical stock prices for free. … -

Trading Direction and Volatility—Flavored Ratio Spreads

|Ratio spreads allow traders to express opinions on both underlying direction and implied volatility. Using equity options in conjunction with stocks and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) can be a great way… -

Tom Sosnoff Builds Futures

|Investors and traders looking to expand their market activities beyond stocks, exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and equity options may want to tune into a recent TradeTalk with tastytrade founder and co-CEO… -

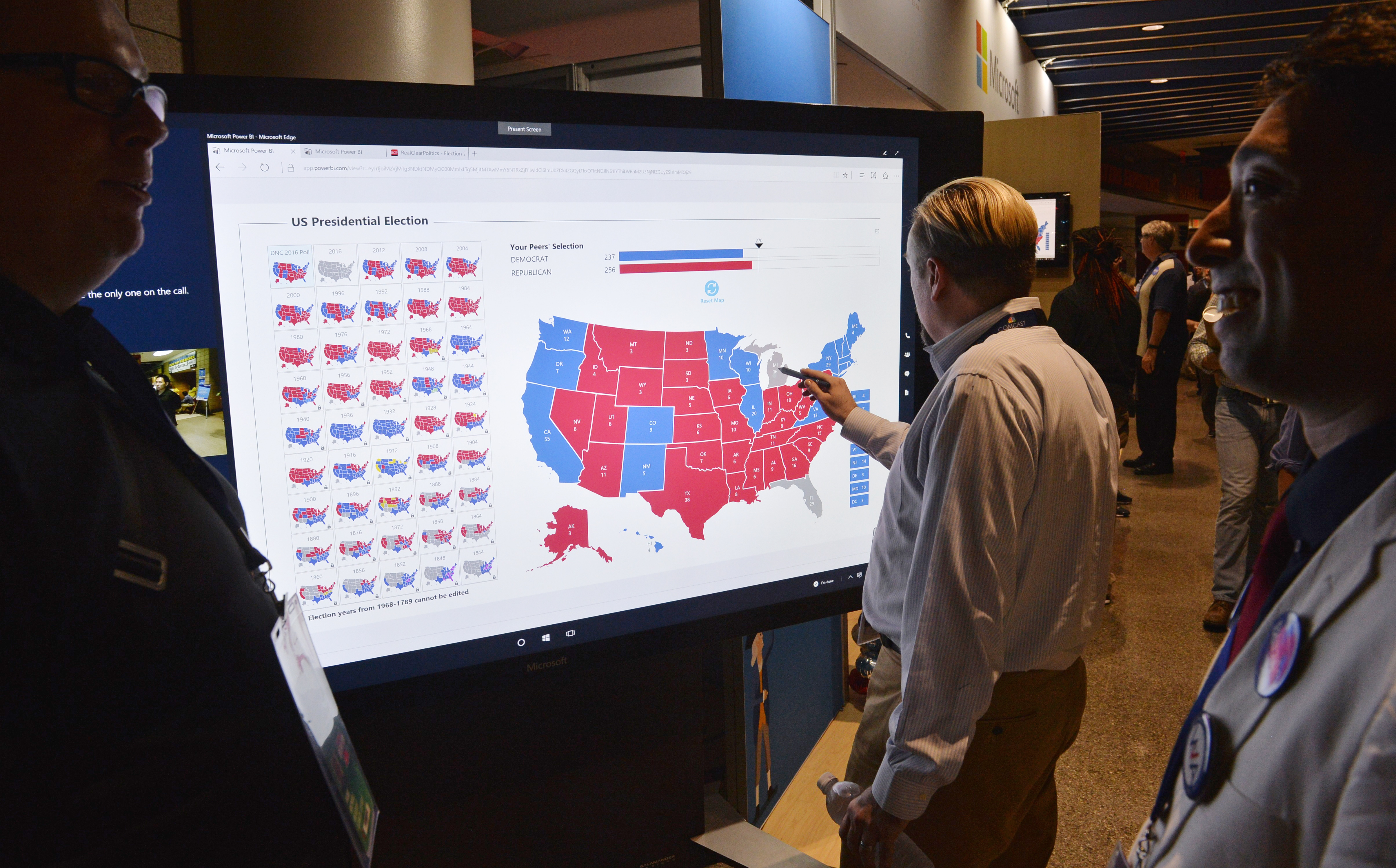

Exploiting Election Week Volatility

|Stock options can triple in volatility as election day approaches, creating opportunities for traders to sell when prices skyrocket Expectation of movement in the markets helps determine the price of… -

Taking Equity in Futures Options

|Equity options traders often rely on implied volatility to assess opportunities, but the practice isn’t limited to the equities segment of the financial markets. Futures traders can also utilize volatility—and… -

Low Price, High Risk

|Beware of low-priced high-volatility stocks—they’re usually no bargain Novice investors are attracted to stocks that sell for low prices, say $5 or less, because they can own a significant number… -

The REIT Trade

|Real estate investment trusts tend to pay dividends that can ease the pain of a bad trade Got a bad trade? Tell everyone you bought the stock for the dividend.… -

Volatility Risk: It’s All About the Vega

|When implied volatility moves up and down a lot, as it has been in recent months, many traders and investors become more attuned to their portfolio’s exposure to vega. For… -

Equities Too Volatile? Consider Some New Shorts (Bonds, Currencies, and Precious Metals)

|With equities making big moves in both directions during the first five months of 2020 (underscored by a 1,800 point drop in the Dow Jones on June 11), it’s reasonable…